Making Space, Part 1

Welcome to the first week of Unfinity card previews. It feels so good to write that. Today, I'm going introduce all the design teams, walk through how we designed the two main mechanics, and show off a bunch of card previews. So, strap in, it's finally time to talk Unfinity.

If you're interested in preordering Unfinity, check with your local game store or preorder from online retailers like Amazon.

Space Explorers

Once Unfinity was on the schedule, but before teams had been selected for it, I talked with Aaron Forsythe, my boss, and asked if I could do something a little unorthodox. Normally, I'll lead exploratory design and vision design for a set, but I'd never led set design. Would it be possible for me to lead the set all the way through from the very beginning of the design to the very end?

Aaron said that I have to make sure I have someone on the team who was good at play design (as it's not my strong suit) and listen carefully to them, but provided I did that, I could do it. That means I led all the design teams for Unfinity, so today, I'll be the one introducing them all. I should note Unfinity went on a little longer than the average design, and had more swaps than a normal set, so the total design team is a little larger than normal.

Click here to meet all the Unfinity designers

Chris Mooney (exploratory/vision/set – strong second)

Chris was my strong second for the entire duration of the design (and thus, the only person, other than myself, to be on design the entire time). They took care of the file and did a huge number of administrative tasks, which was much more for Unfinity than a normal set. For example, figuring out how to mock up stickers in a way that mimicked how they'd appear in boosters so we could play with them was a huge undertaking on its own. Chris's fingerprints are all over this design, and they were a giant help in both crafting the structure and making individual designs. It turns out, they really are a great designer.

Annie Sardelis (exploratory/vision)

Annie is great at what we call "blue sky design," that is, design not beholden to any previous design choices, exploring virgin design space. That's the kind of person you want on an Un- set, especially in exploratory design and vision design. Annie pitched a lot of off-the-wall ideas, some of which weren't even doable, but they helped shape what Unfinity would become.

I believe Annie designed the first card in the file that ended up making it to print: Animate Object. She brought the design in one day for a playtest, drew it, animated hand sanitizer, and we all knew it was going all the way. Annie also served as the card conceptor for the set, figuring out what each spell represented creatively, and added so many wonderful jokes to the set. Look carefully at all the art to see if you can find all the Easter eggs Annie and the artists hid there.

Belle Farmer (set)

Belle was a summer intern that was on set design for the duration of her internship. An Un- set is not the easiest first design to work on, but Belle attacked the task with unbridled enthusiasm. One of my favorite interactions happened early on when she asked, "Can I do this?" and I replied, "It's an Un- set, you can do most things." From then on, she never backed down from experimenting and trying crazy ideas, some of which you all will get to play with.

Daniel Holt (vision)

Daniel's day job is a graphic designer, creating frames and symbols, but he's also a good designer, something I learned working with him on Kamigawa: Neon Dynasty. Un- sets like to do weird stuff, so I thought his mix of design skills coupled with an expert understanding of what graphical components would be needed to sell an idea, made him a perfect choice for the design team.

Donald Smith, Jr. (vision)

After Aaron promised I could lead the set the whole way through as long as I had a play designer to listen to, I walked directly to the Pit to Donald. I've worked with Donald on a couple of Vision Design teams (Theros Beyond Death and Streets of New Capenna), and I've always enjoyed how he thinks about the game.

Donald came to Magic later than most of the other play designers (he started on the Pro Tour), so it's always fun to watch him learn of cards from Magic's past. I thought he'd enjoy embracing the craziness of an Un- set, so I approached him at his desk to see if he would be interested. He was and served on the team for the entire vision design.

Hitting the right power levels is hard in any Magic set, but as you pull away from things we've done before it gets harder, and Un- sets are all about exploring unknown space. Donald was up for the challenge and guided me in how to think about the best way to keep the set fun but fair.

George Fan (exploratory/vision)

George Fan is probably best known as the designer of Plants vs. Zombies (although he's designed other great games). I met him when I gave him a VIP tour at Wizards. He and I became friends. During the Great Designer Search 3, George informed me that he had entered but was knocked out during the multiple-choice test. He thought it would be real fun to work at Wizards for six months. I told him there were ways for that to happen beyond him winning a Great Designer Search.

His six-month stint ended up becoming a year. During that year, we started working on Unfinity, and it seemed irresponsible of me not to have him on the Exploratory Design and Vision Design teams. (He'd probably have been on the Set Design team if his year hadn't finished.) George loves designing offbeat things, so he was perfectly at home designing for Unfinity.

JC Tao (set)

Donald was the play design expert for vision design, but he couldn't do set design due to other responsibilities, so JC was brought in. Like Donald, JC also came from the Pro Tour, and he was excited by the challenge of balancing a set as quirky as Unfinity. I listened carefully to everything JC had to say, and I think the set was much improved for his involvement.

Mark Purvis (set)

Mark is the second biggest Un- fan at Wizards. He was part of the Council of Marks that got Unstable made, and he helped shepherd Unfinity from an idea to an actual set on the schedule. He served as the product architect for the first half of Unfinity's existence (handing the job off to Mike Turian) and asked to be on the Set Design team.

My favorite story of Mark during set design is that he went out and got actual stickers for us so we could try playing with real stickers in the shape of objects. He showed up to the meeting with the box he ordered, which had more sticker sheets in it than I'd ever seen in one place before. I was glad to have Mark as part of the design, as he has been such an ally in getting the Un- sets made.

Matt Tabak (vision)

Matt has a great sense of humor and enjoys the sillier side of the game, so he volunteered to be the editor for this set. Matt asked to be on the Vision Design team to get a sense of what the set was like. Un- sets have many more challenges than the average set for an editor, but Matt was always up to the task.

Noah Millrod (set)

Noah doesn't work in R&D, but he's a good designer, so we put him on design teams from time to time. Noah had asked to be on Unfinity, a quality that I look for in an Unfinity designer. Noah has a good eye for what is and isn't working on a card, and always gave good advice about how to make a design better. He designed a lot of cards that you all will have fun playing.

Robert Schuster (exploratory/set)

The first day of design, Robert informed us that he was afraid of clowns and balloons. I told him he was on the wrong design team. Robert managed to face his fears though and was an excellent contributor, always giving us vantage points to think about that we had not. Robert was the only designer to work on exploratory design and set design but not vision design.

Taymoor Rehman (set)

Taymoor is a designer with a very critical eye. He likes to challenge assumptions and really gets to the heart of what a card or mechanic is trying to do. I appreciated his ability to help stress test elements of the set, and I think the set is improved by us answering the questions he was asking. He also designed some fun cards.

Mark Rosewater (exploratory/vision/set – lead)

There's not much to say about me that you don't already know. I can say that I learned a lot from doing this set, as, for the first time, I got to lead the design of the second half of the product. I have lots of experience doing the initial design but far less helping get a product to the finish line. Unfinity taught me a lot about aspects of making Magic sets that I was unfamiliar with.

Sticker Shock

A couple of years before Unfinity began design, we did a Hackathon about possible future mechanics. (A Hackathon is when many R&D folks take a week off to explore new ideas.) The team I ran was about designs using components outside the deck, things like punch-out cards or generated game pieces like the Monarch.

One of the ideas that came up was stickers. Stickers had shown up in an even earlier Hackathon when a team explored what making a Legacy version of Magic would look like (a Legacy game is one where the game pieces permanently change over time). We had made stickers for a D&D product, so we were aware that our production team knew how to produce them, and they seemed like a prolific open-ended tool to do cool stuff. The Hackathon team probably spent an hour brainstorming what we could do with them. There were enough interesting ideas that I filed away stickers as a thing I wanted us to try one day.

Once we got the green light for Unfinity, I thought back to that hour of sticker brainstorming from the Hackathon. Un- sets push into new design space, and stickers had this really exciting quality to them that felt like a perfect fit for Unfinity.

Our first exploratory design meeting for Unfinity was spent doing a new brainstorm session over what we could do with stickers. I did have one caveat, though: I didn't want the stickers to be permanent. The goal wasn't that you were forever changing your card but rather that you were temporarily changing it for the game. I had talked with production about whether we could use a lighter glue on the stickers that would help them come off without harming the stickered card and could be restickered numerous times. I was told they had to test it but believed such a goal was possible.

Our early sticker brainstorming did a lot of boundary pushing. What if you used stickers to attach different cards together? What if you could sticker other players? What if you could sticker inanimate objects? (That last one did make it to the set with Animate Object.)

In the end, though, the most practical use for stickers was stickering cards. The idea we kept coming back to was how much fun it would be to have stickers of objects that you could then sticker on the art of your card. For a little while, we entertained that all the stickers would be pictures and that adding stuff to your art was their only function. To make this matter mechanically, we could have cards that improved when stickered or cards that enhance stickered cards. We also toyed around with the idea of having art matter.

The biggest problem we ran into was that a lot of art was subjective. Even what constituted a "blue object" was argued about. In the end, we decided it might be fun to have some "art matters" at high rarities, but we had to be very careful with what we did at common and uncommon. The object we found people argued the least about was hats, so we decided we'd make that the "art matters" theme at low rarity. (More on the "hats matter" theme next week.)

As we played around with stickers, it became clear that there were a few areas that just played well. Abilities and power/toughness seemed like things you would want to manipulate with stickers, and "names matter" kept popping up, as caring about the quality of names was something only Un- sets could do.

One meeting, we talked over all our ideas and whittled them down to four things we felt we could make stickers of: names, art, ability, and power/toughness. We did have one small problem though. Art and names didn't inherently mean anything. Yeah, we could make cards that cared, but most of the time, it was more decorative (which definitely was fun) than functional. In contrast, ability and power/toughness stickers always mattered. No other card had to interact with them to make their change viable. This led to a bunch of early playtests where no one ever stickered the names or art stickers and only used the ability or power/toughness ones.

The solution to this problem was to have cards dictate what stickers you could use. If a card only lets you sticker an art sticker, well, that's what you would use. This then allowed us to charge more for cards that stickered ability or power/toughness stickers.

This led to a new problem. You would get three sheets of stickers, and there were fun things on your sticker sheet, but you'd only get cards that used certain types of stickers, so some of the stickers would be stuck on your sticker sheet, never to be used. This just didn't feel right. Part of the fun of stickers was stickering what you wanted to sticker. In addition, because all ability and power/toughness stickers had the same cost to them, it meant we had to keep them in a similar power band, which greatly reduced what we could do with them. All of this forced us to tackle the ability and power/toughness issue in a different way.

The next attempt was using a mana gate. Names and art stickers would be free, but if you wanted to sticker an ability or a power/toughness sticker, it would cost extra mana. The problem with this execution was that most of the cards that sticker already required mana, either because you had cast them or because you had activated them. This led to a world where ability and power/toughness stickers didn't get used until late in the game, which greatly decreased their impact. In addition, the extra mana was bulky, and it added another layer of complexity to using them and made them less fun to use.

Next, we decided that we wanted to explore using another resource. Well, it turns out at the time that Attractions were using another resource (more on Attractions in a moment): tickets.

Tickets were like energy in that they were counters given to the players. It seemed odd to create two different resource systems, so we started using tickets for stickers. The system was pretty straightforward: the cards that let you sticker also gave you tickets, so over time you could save up to cast the ability and power/toughness stickers. We ended up making the floor for tickets cost 2, so players could use some of them earlier, and the top-end cost 6, so players had some big effects to aspire to.

Tickets proved to be a great resource for stickers, but combining them with Attractions was causing numerous issues. There were play design concerns as it's hard to have a resource function for two different ecosystems. Also, it made the set a little too ticket-centric, and made stickers and Attractions feel more similar than we wanted, so we removed them from Attractions (there were other Attraction-oriented reasons as well, which I'll get to below).

We'd known from the beginning that there was going to be 48 sticker sheets, as that's the size of the die-cut stamp. To make stickers, you put them on sticker-stock and then have a giant stamp that cuts them out when printing to allow you to individually peel them. The size of that stamp is locked, and it's the size of a six-by-eight collection of Magic cards.

Because I always try to make Un- sets have the highest variance of any Magic set, as variance is fun but problematic for high-end competitive play, I wanted each of the 48 sticker sheets to be unique. That also meant I didn't want to repeat any component. In the end, the only thing we were forced to repeat were power/toughness combinations as there weren't enough of them.

In early playtests, we drafted the sticker sheets, but we found it was creating too much decision paralysis, as there's a lot going on with each sticker sheet. We solved this issue by making two changes.

One, we decided not to have players draft the sticker sheets. In Draft, you just get what you open. (We strongly encourage you to play Unfinity in Limited by drafting, as that's how the set was built, but if you still opt to play Sealed, you choose three of the six sticker sheets you open. In Constructed, you choose at least ten unique sticker sheets and randomly choose three before each game.) Two, we lessened the number of ability and power/toughness stickers on each sheet from three to two. (We were also having space issues, so two birds, one stone.)

The last big change to stickers came late in the process when we made the decision to split the set into Eternal and acorn-stamped cards, the former being legal in Eternal formats (Commander, Legacy, Vintage, and Pauper). In order to make the sticker sheets work within the rules, we had to make one concession. Up until that point, a sticker stayed on a card until the game ended no matter what zone it went to. (It worked a lot like "perpetually" in Alchemy on MTG Arena, but it existed before that mechanic had been created.) The rules can't handle permanent changes in hidden zones, so we changed stickers to fall off and go back to the sticker sheet if a card went to the library or hand.

This change actually only impacted a small handful of designs, most of which we could redesign to match their original intent, using things like exile or allowing you to cast stuff from the graveyard, so it seemed like a small cost to allow the majority of the sticker cards entry into Eternal formats. It also opened up a new area of strategy where you purposefully send a card to a hidden zone to reclaim the sticker, so you could put it onto another card.

Finally, I just want to walk through how stickers are used. When a card lets you sticker a card, you are allowed to sticker any non-land permanent you own. Originally, we allowed you to sticker lands, but because they are much harder to get rid of, it was causing play-balance issues with some of the stickers, and we decided we'd rather have more powerful stickers available than have stickered lands.

Only allowing you to sticker cards you own was implemented from the beginning because we didn't want to force players to have their cards stickered if they didn't want them to be. (Not stickering cards you don't own is baked into the rules, so even if the card doesn't specifically state it, it's true.) I should point out that you are allowed to use paper and pencil in place of stickers if you'd rather do that. Other than a small handful of acorn cards that care about sticker size, it doesn't matter how big you make your stickers with paper.

Power/toughness is the only replacement sticker, meaning you only have one power/toughness combination, and that's the last sticker you used. Name, art, and ability stickers are all additive, meaning their addition does not remove anything from the card. In acorn games, names can be put anywhere in the name. For example, if you have a Grizzly Bear and the name sticker "Dark," you can make it Dark Grizzly Bear, Grizzly Dark Bear, or Grizzly Bear Dark. For Eternal games, all the rules care about is that it has the sticker, so placement doesn't matter. You must always pay the ticket cost to sticker ability or power/toughness stickers. You get the tickets first, so you can use them for the sticker effect that generates the tickets.

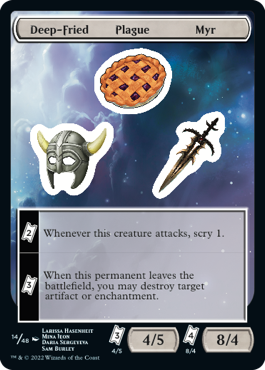

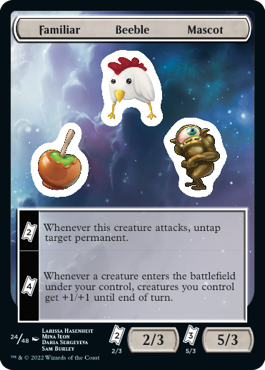

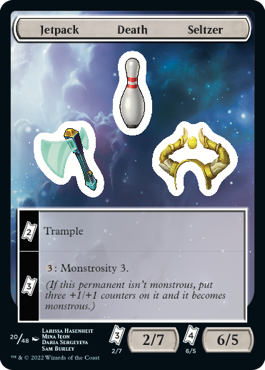

Before we move on to Attractions, I want to show off some new sticker sheets. Again, there are 48 total with repeats only with the power/toughness combinations.

Click here to see them

What's the Attraction?

The other big mechanic of Unfinity is the Attractions. Unfinity was designed as a top-down set, so one of the important things we wanted to capture was all the cool rides, games, and stands you would find at a carnival/amusement park. We knew from the beginning that they would be in a separate deck but were interested in going a different direction than Contraptions had gone in Unstable.

The first incarnation of the mechanic had them being their own card type, Attraction, with three different subtypes, Rides, Games, and Stands. Rides originally affected your creatures in some way, Games let you play a subgame, and Stands let you get resources. The original Attractions went to the battlefield, and either player could visit them for a mana cost. We wanted a mana cost because we needed some way to adjust for different power levels, as the design space was much wider if everything wasn't in the same narrow power band. Originally, they all went to an area called the Midway (which we weren't sure if it would be on the battlefield or not).

This led to our first problem with Attractions. You would spend mana to play a card that would open an Attraction (those are the words we use to draw an Attraction card and put it onto the battlefield), and then you wouldn't have the mana to visit it, meaning your opponent would most often get to use it first. This just felt bad, as you spent all the resources to get it onto the battlefield and your opponent benefitted from it before you did. Our next attempt made the activation cost to visit an Attraction cheaper if you controlled it. This allowed you to use it more often but still didn't prevent the "my opponent got to use it first" problem.

That's when we came up with the idea of tickets. Instead of just a mana cost, the Attractions also had a ticket cost that you could use in place of mana. Then when you opened an Attraction, we gave you a number of tickets equal to one visit. This way, when the Attraction entered the battlefield, you were guaranteed to visit it first. It also allowed us to give you tickets through other means to give players a way to visit more Attractions.

We then tried a version where you got tickets if your opponent visited it, so the more they used it, the more you got to use it for free. It was around this time that stickers were struggling for an alternate-resource system, so we tried using tickets for both. Tickets ended up working much better for stickers than for Attractions (for numerous reasons, but the biggest was because of the alternate mana cost built into Attractions). We tried only allowing tickets as a means of entry, but that was making Attractions a little too parasitic.

As I said above, we found that trying to balance tickets when they were essentially running two different ecosystems was too much pressure, and the pervasiveness of tickets made everything feel a bit too same-y. This led us to the idea of Attractions just giving the person who opened it a free visit, so that they would open it and then visit it right away.

This was the closest we'd gotten to making it work, but we were discovering that we had a bigger problem on our hands. No matter what we did to balance it, we found playtesters just didn't like the idea that they spent resources on something that was helping an opponent. We were making changes to improve the problem, but Attractions were getting played less and less over time. It was then we decided to start over.

We started this redesign by asking ourselves what we liked about Attractions:

- We loved their top-down flavor. For example, let me show off my first Attraction preview for today.

Click here to see Concession Stand

You visit the Concession Stand to get Food. That was just slam-dunk flavor. You'll notice that there are four different versions here. They are all the same except for what numbers are lit up and what flavor text they get. I'll get into what the numbers mean in a second.

- We enjoyed them being from a separate deck. Just making them artifacts/enchantments you cast from your deck didn't feel special enough for an Un- set, and it didn't allow for the interactive flavor we wanted with other cards.

- We wanted some amount of variance built into them. Drawing from a randomized deck helped, but we were curious if we could do something that raised the variance if possible. A signature trait of Un- sets is that they have the highest variance of any Magic set. Variance is a lot of fun but makes the game less consistent. That's fine when you're highlighting having a good time, but less so when using the set during a major tournament with a lot riding on it.

With those three things as our starting points, we asked ourselves what we could do. When making the original version of Attractions, we made a conscious decision to make different choices than Contraptions whenever we could. Both Contraptions and Attractions were extra deck mechanics, and we wanted them to feel different. When reexamining Attractions, we decided we could do some things Contraptions did if that led to better gameplay.

The first big decision was to only let you access your own Attractions. We had tried hard to do the "everyone can visit them" model, but even if we could solve the balance issues (making them strategically the right call to use), we didn't know how to overcome the bad impression they created when your opponent benefited from them.

The next decision we made was to add an element of variance (as I discussed above). The reason for this is that we wanted to take extra decks in a different strategic direction than Contraptions. I like to compare extra decks to double-faced cards. They are a mechanical tool with a lot of flexibility that allows a Magic designer to tap into different veins of design. Traditional double-faced cards (TDFCs) and modal double-faced cards (MDFCs), for example, have many similarities but function quite differently in how they play strategically.

Contraptions used an extra deck to create a sprocket system that allowed you to map out the future. Every decision you were making with Contraptions gave you the ability to figure out what was going to happen on each future turn. This would allow you to think many turns ahead and act in ways where you could play out long-range strategies. We wanted to take Attractions in a different direction. What if Attractions did the opposite? What if the outcome wasn't known so it was more about adapting to what happened rather than planning ahead? This was also skillful, but in a very different way. To do this, we had to add some kind of unpredictable variance. Well, Unfinity already had a randomizer built in: die rolling.

Die rolls had been introduced to Magic in Unglued and then brought back in Unstable. They would later be brought to Standard in Dungeons & Dragons: Adventures in the Forgotten Realms, but that hadn't happened yet. (I'll talk more about how we added die rolling to the set next week.) Die rolls seemed to be the low-hanging fruit we needed to solve our problem.

The earliest version of the die-rolling Attractions was as such. Attractions all tapped to use their effect, but they didn't untap as normal. If you had at least one tapped Attraction, you would roll a six-sided die during upkeep and untap any Attraction with that number lit up. We then tried a version where Attractions didn't tap, but you could visit any Attraction that had a lit-up number that you rolled at the beginning of the turn. Finally, we chose to have the die rolling happen at the beginning of the first main phase (the same time Sagas advance) and have you visit all the Attractions with the lit-up number then and there to keep it clean (with you getting to choose the order in which you visit them).

A nice effect of the lit-up numbers is that it gave us the chance to gate the power level of abilities. For example, an effect that was lower in power could have four untap numbers, while one that was more powerful could have just two. We did explore having just one and five untap numbers, but one ended making it happen too little and five times made it happen almost all the time. We also decided to help increase excitement at the time of the roll by making 1s always miss and 6s always hit. That way when you're rolling, you always have a dream and a nightmare scenario, adding tension to every roll. I also believe it was around this time we decided to make Attractions artifacts rather than a new card type. It just made them easier to interact with.

Once we knew we were going to use die rolls, I insisted we take advantage of the fact that there were multiple copies of each Attraction on the printing sheets to allow us to have a variety of lit-up numbers for the same Attraction. How many was based on how many light combinations there were and what rarity it was as that affected how many possible cards it had access to.

Let's use Concession Stand as an example. It has two untap numbers. Neither can ever be 1, and one has to always be 6. That leaves four options: 2/6, 3/6, 4/6, and 5/6. Concession Stand is an uncommon, and there are at least four copies on the uncommon sheet, so it could have every possible variant—four in all. We chose to give each variant its own flavor text because we had a lot of fun writing the Attraction flavor text. There's one other variant that happens in different versions (on three cards), which leads me to my next preview card.

I talked about how, early in the creation of Attractions, we had some that we called Games where you played a subgame with the chance to win a prize. In the earliest version, you played against your opponent with the winner getting a prize. Again, it felt bad that you could spend the resources and your opponent won a prize. This led to a version where your opponent couldn't win a prize but nonetheless tried to stop you from winning. In the end, we found the most fun games were either solo or wanted another person to work together with, so we added in outside assistance (another theme I'll talk about more next week). All the games pay out a prize if you win and then have you sacrifice it and replace it with another Attraction. There was a period where the games didn't go away when you won, but we found players good at a particular game were just winning a prize each turn. My next preview card is an example of an Attraction that's a game where you involve a person outside your game.

Click here to see The Superlatorium

Three games, which all have six versions, have different qualities on the six different cards to have the game play out differently. For instance, The Superlatorium asks you to predict which card an outside player will judge as the ________-est. Each card gives you three different options. The reason there are six different options is that it has three lit-up numbers (2/3/6, 2/4/6, 2/5/6, 3/4/6, 3/5/6, and 4/5/6).

I have one last Attraction to show off. Concession Stand was a stand, The Superlatorium was a game, so it's time to show off a ride.

Click here to see Hall of Mirrors

This is an example of the bigger effects we can do on rare Attractions. The reason there are only two versions has to do with the size of the rare sheet. While two lit-up numbers have four options, there are only two copies of each rare on the rare Attraction sheet, so we only had the ability to do two versions. We did make sure to balance 2 through 5 across the rares that don't get to have every variant. (This means it's not better to roll any number from 2 through 5.)

I know I've been extra wordy today, but I have a lot to say about Unfinity and only so many columns, but I can't leave without showing two last preview cards.

The first, created by Chris Mooney, shows off the woman who owns the Astrotorium, Myra the Magnificent.

Click here to meet Myra

Regular

Galaxy Foil

Showcase

Galaxy Foil Showcase Because it's Myra's show, we wanted her to work with Attractions. Chris created a fun build-around card that can serve as a Commander to make a sweet Attraction deck. Note that because Attractions aren't a color, you can use all the Eternal ones in a Commander game (and the acorn ones if your play group allows it).

My final preview card is one I designed, and it's one of my favorites from the set. It was something I knew we needed to have from before the design even began. In Unglued, I'd made the card Timmy. Unhinged had Johnny. Unstable had Spike. Those were all three of the player psychographics, but there were two aesthetic profiles that players associated with them. I couldn't make a fourth Un- set without including one of them, so without further ado, click below to meet Vorthos.

Click here to meet Vorthos

Regular

Galaxy Foil

Showcase

Galaxy Foil Showcase I've always wanted to make a Commander that allows you to build around a character, and Vorthos seemed like the perfect fit. Vorthos was purposefully given a five-color identity, and a mechanic that helps you cast all colors, to allow your deck to truly be about the character you're focusing on. I hope the Vorthoses have a lot of fun with Vorthos.

Space, the Final Frontier

At over 6,000 words, this column is a little longer than most, but I have a lot to say and only so many columns to say it in. I hope my passion for this set comes through as I tell you the story of its design. Even more so than normal, I'm eager for feedback. What do you think of stickers? Of Attractions? Of the preview cards? Of Unfinity in general? You can email me or contact me through my social media accounts (Twitter, Tumblr, Instagram, and TikTok) with feedback.

Join me next week when I talk about the rest of the set's design and show off more preview cards.

Until then, may you embrace the more casual end of the Magic spectrum.

#967: Rise & Fall of Blocks, Part 2

#967: Rise & Fall of Blocks, Part 2

33:46

This is part two of a two-part series talking about the history of blocks.

#968: DMU Set Design with Erik Lauer & Ian Duke

#968: DMU Set Design with Erik Lauer & Ian Duke

33:24

In this podcast, I sit down with Erik Lauer and Ian Duke, the co-lead set designers of Dominaria United, to talk about the expansion's set design.

- Episode 966 Rise & Fall of Blocks, Part 1

- Episode 965 DMU Vision Design with Ethan Fleischer

- Episode 964 Concurrency