Like Father, Like Son

On Wednesday, April 17, my father, Gene Rosewater, died peacefully in his sleep. He suffered from Alzheimer's disease and aphasia, and his health had declined over the six months prior. My father was a diehard gamer and is the reason that I got into gaming. When I was first offered a job at Wizards, I was a bit conflicted as I had always envisioned being a writer (with a long-term plan to create television shows), so I called each of my parents to talk with them about the decision.

My mom was initially skeptical of the idea. She knew how much I enjoyed writing and wasn't entirely sure that becoming a game designer was the right path for me. (She did eventually come around to the idea.) My dad, on the other hand, was immediately all in. "That sounds amazing," he said, "You should do that." (I recorded a podcast with my dad back in 2013 that includes this story and more if you'd like a chance to get to know him.)

Whenever someone I know passes away, I have a moment I call the "It's a Wonderful Life reflection." I imagine what the world would be like had that person never existed. It's nice to think about the impact they had. Had my dad never existed, or imbued in me a love of games or encouraged me to take the job at Wizards, I feel it would have impacted all of you, because Magic would be different.

I believe that a designer is shaped by their experiences and their relationships. My dad had a huge impact on my life and, as such, shaped how I think about games and design. For today's article, I am going to talk about some lessons he imparted on me and how those lessons shaped my design philosophy, including how I design Magic sets, mechanics, and cards.

"If you're not enjoying the game, change the rules."

This was an early lesson I learned from him. If we were playing a game and my dad didn't like how it was playing, he'd change the rules until he liked how it played. As a game player, he taught me that you are empowered to make the game what you want it to be. Games serve the players, not vice versa. This completely shaped how I thought of games, and I think it was one of the things that most drew me to Magic. The power for the player to adapt the game is built into Magic. It's a core part of both its structure and its philosophy.

When I design a card, mechanic, or theme, I think of it as making a tool, a resource, to empower the players to make the game they want. That means adding flexibility where I can. That means making the card open-ended when possible to maximize its ability to combo with other cards. That means thinking about what game resources the card interacts with to create a larger structure that supports the player having options. The question I ask myself isn't "What will they do?" but "What can they do?" If I'm doing my job right, the players will come up with uses and combinations for my designs that I never thought of.

Gene Rosewater Magic Trivia Question #1

My dad designed one Magic card. It was a Tempest card with the playtest name Radio-Controlled Flyer. Which card was it?

-

Click here to see the answer

-

Telethopter Telethopter . You tap a creature because they're controlling the radio-controlled flyer. My dad had mentioned the design for this card, and I liked it, so I put it into the first set for which I led design, Tempest.

"The players make the game enjoyable."

This was one of those things my dad said that I originally didn't believe. The players don't make the game fun, I thought, the game makes the game fun. But then I had an experience that made me understand what my dad was saying all along. In college (I went to Boston University), I had a group of friends that enjoyed playing games. We loved going to the game store as a group, buying a new game, and taking it home to play. Our track record was amazing. All the games we picked out were tons of fun.

When graduation came, we divvied up the games we had bought. I moved out to Los Angeles to become a writer and made new friends. They weren't diehard gamers like my college friends, but they occasionally liked playing games. One night, I had people over and brought out one of the games we'd played all the time in Boston. It was one of our favorites. We played the game, and it was horrible. My friends made fun of me for how bad it was. How could this game be so fun in Boston and so unfun in Los Angeles?

That's when I finally realized what my dad said was true. Games provide a means by which a group can enjoy themselves, but the crux of the enjoyment comes from interacting with friends. My Boston playgroup had learned how to use games as a tool for their enjoyment. My Los Angles friends had not. They still had a good time that night poking fun at the game. (They made fun of me about the game for years.)

This lesson taught me two things, one from my Boston playgroup and one from my Los Angeles one. My Boston playgroup taught me that I have to consider not just how my game pieces will be used within the context of the game, but what social interactions they will create. For example, back in 2018, I wrote an article about a concept called "narrative equity" where I explained the value of your game creating memorable moments that lead to stories. It's not enough to think about how your game pieces interact. You must think about how your game players interact with those game pieces.

My Los Angeles playgroup taught me the importance of making the fun part of the game the core experience of playing the game. Gameplay becomes an integral part of a group's experience when it includes discovering fun aspects of the game as a group. My Boston playgroup knew how to find the fun, but it's not the player's job to do that. Players need to stumble across the fun in your game no matter how they play. How you structure your game, lay out your incentives, and reward players must always revolve around the larger goal of consistently pushing them toward the fun of the game.

Gene Rosewater Magic Trivia Question #2

The first week of what expansion's design was done in my father's house in Lake Tahoe?

-

Click here to see the answer

-

Invasion. Bill Rose, Mike Elliott, and I traveled to my father's house to get away for the first week of Invasion design. We worked out most of the basic structure for the set during that week. Interestingly, the first week of Tempest design was done at Richard Garfield's parents' house in Portland. Two examples of parental support in Magic design.

"Do what fills you with joy."

My dad had five great loves: games, computers, working with his hands (he did a lot of woodworking and metalwork), photography, and skiing. His parents encouraged him to be a doctor, so he chose a field where he could work with his hands, dentistry. He built a dental practice in downtown Cleveland. But dentistry wasn't his passion, so in his 50s, he sold his practice, moved to Lake Tahoe, California, and became a ski instructor for 25 years. He set up his garage to be a wood- and metalworking studio and made endless items. He took numerous photos, adorning walls throughout the house. My house is filled with many of his crafts and photos. And, of course, he played a lot of games, many on his computer.

That's why when I said I was thinking of being a game designer, he was so encouraging. He knew how much I loved games in general, Magic specifically, and felt it would make me happy, which it obviously did. Much of my career has involved getting to the position I wanted, being head designer for Magic, and then resisting all influence to move away from that position. The fact that I spent my life dedicated to something that brought me so much joy made my dad very happy.

This philosophy sticks with me as I design Magic. Here's how I think of it: For each player, there are aspects of the game that bring them great joy. My job, and the job of R&D, is to figure out which game components bring the greatest joy to the most players and include as many of those as I can in each set. Magic's modular nature means that it doesn't require a lot of any one thing from any one set because you can mix and match fun aspects with fun things found in other sets. This desire to understand what people enjoy led me to create the psychographics (i.e., Timmy/Tammy, Johnny/Jenny, Spike, etc.—here's an early write-up on those before they evolved to include more players) and has been a focal point for how I think about our audience.

Gene Rosewater Magic Trivia Question #3

My dad and I played in a big tournament where, at the very last minute, we were told that only cards with no expansion symbols were allowed in the tournament. My dad traded four Revised Edition

-

Click here to see the answer

-

1995 US National Championships in San Jose, California. Bo Bell played a mono-black discard deck. I still don't understand the reasoning for not allowing cards from Arabian Nights or Antiquities to be played.

"Don't be afraid to take risks."

When I was twelve, my parents bought a day camp (along with two other families). Why did they do it? They thought it would be fun. The camp ran for a couple years but didn't work out, and my parents had to sell it. I remember talking with my dad about it years later. I asked him if he regretted buying the camp. He said it wasn't a great decision financially, but sometimes in life, you have to be willing to try things. A lot of opportunities happen because you opt into them, and you can't let the fear of failing keep you from trying.

That piece of advice always stuck with me, and it's something I carry over into my design. I try hard not to shoot ideas down out of worry that they won't work. There are several reasons. One, there have been many times I was skeptical whether something could work only to learn that it could. There are a lot of smart people making Magic, and if you come up with a cool idea, there are always people willing to help you make it a reality. Double-faced cards were an idea, for instance, that I honestly wasn't sure was possible (in Magic; Duel Masters had done them already), but exploration showed they were.

Two, bad ideas can often be stepping stones to good ideas. There's a tendency to view items as either being with merit or without, but a lot of ideas can be flawed in whole with component ideas worth exploring further. For example, chroma was a mechanic that failed in its premiere (in Eventide) but excelled when it was reconcepted as devotion (in Theros).

Three, failure can be a great teacher. There's a lot to learn when something doesn't work. It helps you get a better sense of the parameters you're working under. It can define problematic space that you can avoid. It can point out flaws in your assumptions. In fact, one of the best playtests you can have early on in design is one where everything fails. The iterative process is all about finding things to change, and a disastrous playtest delivers that in volume.

One of my truisms about Magic design is that "the greatest risk is not taking risks." Magic is an ever-evolving game, and we have to be willing to push in new directions.

Gene Rosewater Magic Trivia Question #4

In 1996, my dad and his friend Don attended the Magic World Championship held at the Wizards of the Coast office. Who won that event?

-

Click here to see the answer

-

1996 World Champion Promo Tom Chanpheng from Australia. This is the world championship where the winner got a unique card (only one existed in the world, and I designed this one) imbedded in his trophy. It was at this event that my dad's friend Don informed me of a woman he'd met named Lora who was interested in me. (I was oblivious to this at the time.)

"You want to surprise people every once in a while."

One year for my dad's birthday, my parents told my sister Alysse and me (we were eight and nine, respectively) that we were going to travel to a restaurant in Pennsylvania (we lived near Cleveland, Ohio). We ended up getting lost and found ourselves driving past a resort called Seven Springs. My sister and I asked if we could go and take a look because we had heard about it. Our parents were okay with it if they came along. We asked if we could stay at the resort, but our mom told us we didn't have any luggage. We asked if we could walk in and see the place, and our parents agreed. Once inside, Dad walked up to the front counter with us and said, "Rosewater, party of four."

My parents had planned the whole trip as a surprise, and somehow, even though we drove three hours, my sister and I had no idea. It was such a fond memory that my wife and I did a similar thing with my three kids at a local indoor waterpark and hotel called Great Wolf Lodge. My dad was a big believer in fun surprises. I have a lot of pleasant childhood memories of some great surprises.

I carry this over to my Magic design. I love finding opportunities to do something that the audience will enjoy but not see coming. The split cards in Invasion are a good example of this.

It was the first time we were pushing the boundaries of card frames, and I really wanted it to be something players experienced at the Prerelease, so I made sure we didn't preview any of the five. Then, of course, a whole card sheet was leaked; still, the audience didn't believe they were actual cards. Luckily, not everyone went to the rumor sites, so I was able to go to a Prerelease and watch people open and experience them for the first time. The look on one man's face when he first saw them, as he tried to figure out what he was seeing is a memory I will always cherish.

Many of the Un- sets played around in the surprise space with things like a secret card in Unhinged or alternate mechanical versions of cards in Unstable.

It's a bit trickier to completely hide cards or elements of sets these days with how we preview them (i.e., we show you everything), but I do still enjoy making mechanics or other elements of sets that take some discovery to really understand what they do. Plot from Outlaws of Thunder Junction is a good example of one that's recent.

Gene Rosewater Magic Trivia Question #5

My dad attended one other World Championship, this one in 1997, held in Seattle in the University District. Which pro player won this event?

-

Click here to see the answer

-

Jakub Šlemr from the Czech Republic. The one other fun factoid from this event was that we did a show on it for ESPN2, which I spent most of my time at the event working on. The person we hired to be the on-air talent for the show was a young Jeff Probst.

"Raise your child for who they are."

When my oldest daughter Rachel was born, I called my dad to let him know she was born. While on the phone, I asked if he had any advice for raising a child, and he said, "Raise your child for who they are."

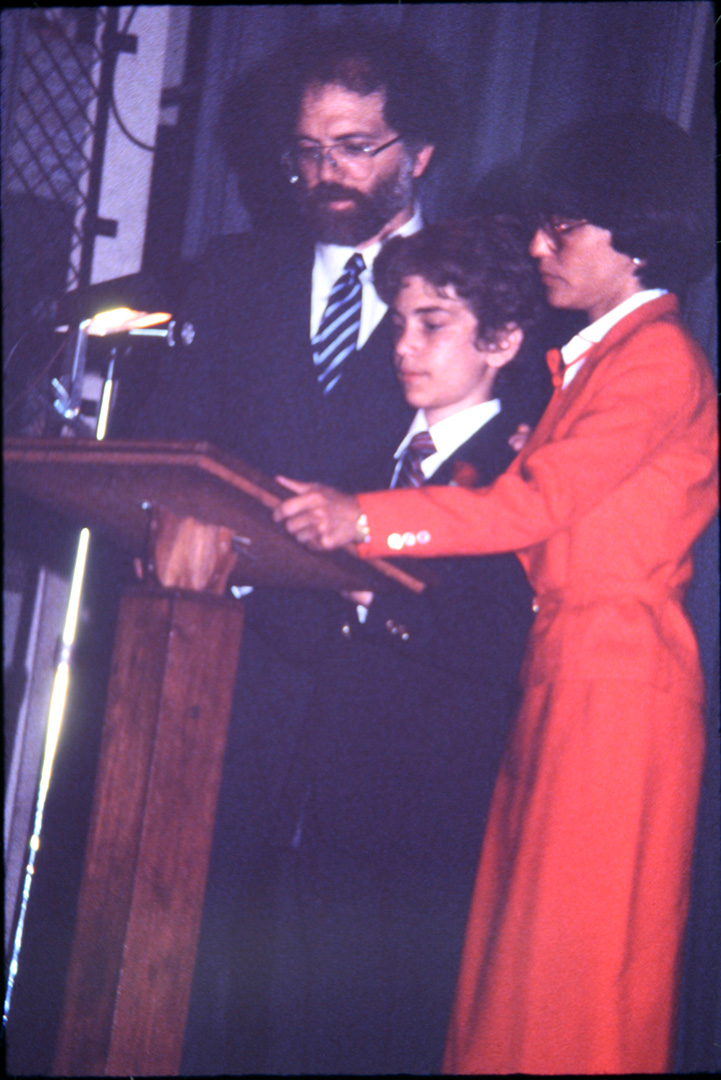

My dad was a jock. He wrestled in high school. He got a wrestling scholarship for college, where he managed multiple times to make it to the state championship, once coming in third. I was not a jock. Other than playing a little softball when I was young, I didn't really play sports. I was a theater kid. I liked to act and write plays. So, my dad helped build sets and was the main photographer for all the productions. He took all the skills he had and applied them to helping me do what I wanted to do. He taught me what good parenting is—helping your child become the person they want to be.

This lesson is easy to apply to design. When I'm designing a set, the goal is not to make it into what I want it to be. A good set design is about figuring out what the set wants to be and then designing it such that it maximizes its own potential. I often get asked how I don't fall into the rut of just making the same set time after time. The answer is I simply let each set become the thing it wants to be. As a designer, it's my job to nurture a set, understand what makes it unique, and then lean into that. I'm super proud of my design of Zendikar, Ravnica, and Innistrad, but much like my three children, each has its own identity, and the reason for my happiness with them is I was able to let each be what they wanted to be.

Today's article is only a small glimpse into who my dad was, but I hoped to give a hint at what a wonderful man he was and how his philosophy about life and games lives on through me and thus through Magic. As always, I'm eager to hear any feedback on today's column. You can email me or contact me through any of my social media accounts (X, Blogatog, Instagram, and TikTok) to let me know.

Join me next week for a return to the Rabiah Scale.

Until then, if you have a good relationship with your parents, and they're still around, give them a call and let them know how you feel. One of the things that has helped me through my grief is knowing that my dad knew how I felt about him and vice versa.