City Highlights, Part 1

December 3 was my 20th anniversary as Magic's head designer. Interestingly, today's column is about the very first block I planned as head designer, Ravnica. My first set as head designer was Betrayers of Kamigawa, but the Champions of Kamigawa block had been created by my predecessor, Bill Rose, and I was trying to follow through on his vision for the block. The Ravnica block was my first opportunity to create a block from scratch. Looking back, there are a lot of things that the Ravnica block introduced that became staples to the game. My plan for today is to talk through several of them, explain how they came to be, and then talk about how they have shaped Magic. The full Ravnica Remastered debut experience starts today (check out Collecting Ravnica Remastered), and I thought it would be fun to give some context to the product. I also have a preview card!

Equal Color Weight for Two-Color Pairs

When I started working on the Ravnica block, then codenamed "Control," "Alt," and "Delete," I knew one thing: it was going to be a multicolor block. The first block to have an overarching theme was Invasion (Bill's first block as head designer), and it was a huge hit. We then went on to have a graveyard-themed block (Odyssey), a typal-themed block (Onslaught), an artifact-themed block (Mirrodin), and a flavor-themed block (Champions of Kamigawa). We'd decided that five years was the right amount of time to return to multicolor. When I started working on the Ravnica block, I was initially concerned about how to make it something that played into the multicolor theme without feeling like a repeat of Invasion.

First, I decided to push in the opposite direction of Invasion. Invasion had the domain mechanic and pushed you toward playing as many colors as you could. Okay, Ravnica would push you to play as few colors as possible. That meant two colors; any less, and it wouldn't be a multicolor block. This led another big decision that I made early, to push back against something we'd done for the first ten years of Magic.

When Richard Garfield made Alpha, it introduced the color pie. A core part of the color pie is that each color had two allies and two enemies. To help highlight this, Alpha had cards that helped its allies (mostly through cards with off-color activations or ones that were boosted by having an ally's basic land type) and cards that punished its enemies (cards with negative effects toward cards of that color or players using cards of that color). Early Magic carried that philosophy by encouraging ally relationships over enemy relationships. We'd make more multicolor ally cards than multicolor enemy cards. And when we made cycles, we would give the ally cycles or the enemy cycles a drawback. They weren't as good as the ally cycles. This resulted in ally-color decks that were much easier to play than enemy colors.

As a huge advocate of the color pie, I appreciated how the mechanics of the game were reinforcing the flavor of the relationships of the colors, but as a game designer, it seemed we were pushing a bit too hard. The game would just be more fun if all the two-color combinations were equally as easy to play. So, I decided that I was going to have all the two-color pairs in the block treated equally. I know this might seem obvious with 20/20 hindsight, but it was a bit of a contentious idea at the time. A lot of Magic design is based on doing what we've done before, so changing how we do something can be a struggle.

My strategy, at the time, wasn't to pitch this as a permanent change but rather something for this particular block. I'd learned over the years that player sentiment could help turn temporary plans into permanent ones. The Ravnica block, being hugely successful, changed R&D's take on the color pairs. From that block onward, we treated them more as equals and generally tried to have them appear at the same quantity and power level.

Hybrid

When tackling a theme, I always like to dig deep and explore how we've handled it in the past. This allows me to see where we've concentrated our efforts and pinpoint room for the most growth. It also allows me to examine where there might be problems that future design processes could help solve. Finally, it allows me to get a better grasp on whether there are new tools to craft. Here are a few things I realized in my deep dive on multicolor design:

Multicolor decks put a strain on mana.

In a monocolor deck, every land helps you cast your spells. But in a multicolor deck, it's possible to get "color hosed," that is, you draw land or mana sources that give you access to a color that isn't on the spells in your hand. That means more games with multicolor cards end up having land issues where players struggle to play their spells.

It's harder to make certain types of two- and three-drop multicolor spells.

The inconsistency of drawing the right mix of mana makes it trickier to create cheaper multicolor cards. This plays out the strongest in two areas. First, in Limited. Players have much less access to color fixing, so hitting multicolor two- and three-drops becomes tougher. As such, we tend to avoid making lower-cost multicolor cards at common. Second, in aggressive play. Two- and three-drops that really need to be played turn two and turn three to be affective are hugely handicapped in multicolor decks because the mana consistency is tricky. We do make some, but they're hard to balance.

You can't make a one-drop.

Traditional multicolor cards require mana in each color to play, meaning they must cost at least two mana.

There's less flexibility.

A red-green multicolor card can only go into a deck that has access to both red and green mana. That means, in a draft, the options for who can draft a two-color card goes way down (even more so if three-color decks aren't viable). This is an added complication in designing multicolor sets for Limited.

We made multicolor our first block-theme return because multicolor is very popular among the players. But as I spelled out above, multicolor brings a lot of challenges to design. This got me thinking. Are there different ways to think about multicolor? And that's when I had my big breakthrough.

To explain, I must first give you a little background on myself. I've always been more of a word person than a numbers person. I often talk about how one of my big influences in Magic design has to do with me being a word person in a sea of numbers people. In college, though, I had to take three math classes as part of general requirements. I got out of one by doing well on my AP Spanish test. (Being a gamer means you find clever ways to accomplish your goals.) One of my math classes was a philosophy class on mathematicians. My other was a logic class. I love puzzles, especially logic puzzles, and saw that my roommates' tests from the class seemed like the kind of thing I do for fun.

In logic class, they teach you a bunch of symbols. Two of them were ^ and ˇ, a caret facing upward and one facing down. The first represents "and" while the second represents "or." "And" and "or" are pretty important functions in logic. Having a whole semester of logic just cemented "and" and "or" kind of being opposites, so one day, while I was looking at some multicolor cards, it dawned on me that we treated multicolor as "and." A blue-black card required blue mana and black mana. What if we turned the "and" into an "or"? What would it mean for a blue-black spell to require blue mana or black mana?

Once I asked myself that question, I got to the idea for hybrid mana quickly. The symbol means you can pay one or the other. The ramifications of hybrid mana hit me quickly. It helps offset mana issues, especially in a two-color deck. If your deck is all hybrid cards, it has the same mana play as a monocolor deck. It makes it easier to create cheaper multicolor spells and even allows for one-drops. Lastly, it increases the flexibility of cards. If you have a green-white hybrid card, anyone playing a deck with white or green could put it in their deck.

I was so excited that I ran around The Pit showing off my discovery. The response I got was "eh." No one was particularly enthralled. I think they saw it as a gimmick that we could put in a set, but I don't think anyone really saw it as the tool it would become. To defend my R&D co-workers, I think hybrid is a strange animal. It hides its potential in that it appears mundane. It doesn't give you access to new abilities and puts stress on a part of the game, color-pie overlap, that's uneven, even more so at the time. (We've worked hard over the years to find more overlap space for certain color combinations.) The strength of hybrid is subtle. To my colleagues' credit, they saw that I was excited by it and encouraged me to figure out what to do with it.

It addressed a lot of multicolor weaknesses, so I put it into Ravnica. The set went through a lot of changes, as I'll discuss next week, but through it all, hybrid stayed in the file. That is, until development started. (For those unaware, original Ravnica was made during a time where the file was divided between design and development, different from today's exploratory, vision, set, and play design delineation.) The set was asking a lot of development (again, something I'll get to next week), and Brian Schneider, the lead developer for Ravnica, decided that hybrid was just a bit too much, so he took it out.

I ended up putting it into the next block, Time Spiral, to show how the time disaster was affecting the very nature of magic. Brian came to me in the later stages of Ravnica development and said that while the structure of the set was unique, the team felt it was light on mechanical innovation, and then he kindly asked me to let them have hybrid back. The plan was to do it lightly in a vertical cycle (common, uncommon, and rare) for each color combination. I said it sounded great. I was happy to see hybrid go back in.

An interesting aside for those who enjoy Magic trivia: Many years ago, I and a few other members of R&D attempted to change the frames for traditional multicolor cards. At the time, they were all gold, and other than the mana symbols, there was no way to tell what the colors of the card were. We suggested a new frame for two-color cards that was half one color and half the other. We made frames for them, but in the end, the majority of R&D felt there was enough momentum and popularity for gold that we shouldn't change. Our solution was to add the colored pin-lines to gold cards to help players tell what colors they were. When hybrid got put back in Ravnica, we needed to get a frame for them, so I suggested we use the frames we'd created when we tried to redo how multicolor cards looked. The half and half of the frame matched well with hybrid's sensibility.

Also, the original plan for hybrid was that its color would match the mana you spent on it. If you had a black-red hybrid card, for example, it would be black if you spent only black and/or colorless mana to cast it, red if you spent only red and/or colorless mana to cast it, and black and red only if you spent black and red and/or colorless mana to cast. One of the last things we changed about it was making it both colors no matter what you spent to cast it, not because we thought the card was inherently both colors (again it's "or" not "and"), but we didn't think the memory issue was worth the pain of tracking. So, the core of the reason it has a two-color identity is based on simplicity of use, not the essence of what hybrid is supposed to represent.

Once the set came out, hybrid was the highest-rated "mechanic" in the set. (I put mechanic in quotes here because I've never viewed hybrid as a mechanic as much as I do a tool.) I believe that at the time, it was the highest-rated item to have ever been rated.

I would bring hybrid mana back in the Shadowmoor block as the backbone of the design (it's almost half the set; a little too high of an as-fan, in retrospect). Hybrid mana quickly became deciduous as R&D found many different uses for it. It helped balance the all-gold Alara Reborn set. It was used to cross between the wedge theme of Khans of Tarkir and the ally themes of Dragons of Tarkir in Fate Reforged. It aided in making uncommon planeswalkers in War of the Spark. It helped Throne of Eldraine cross its monocolor theme with other themes in the set. It was used to make companions more flexible and smooth out a wedge theme in Ikoria: Lair of Behemoths. And the list goes on and on (Zendikar Rising, Jumpstart, Strixhaven, Streets of New Capenna, etc.). In short, it's become a versatile tool for doing all sorts of things, from helping with color identity and bridging themes to broadening the usage of mechanics.

Multicolor Factions

When the Creative team and I talked about the needs for the set, I told them the set has a two-color theme and that I wanted all ten two-color pairs represented equally. Brady Dommermuth was the creative director responsible for the Creative team at the time. While running on the treadmill one day, he had an amazing idea. What if each color pair was represented by a different group and the ten groups made up some larger organization? Brady called them guilds and came up with the idea of a city with a Guildpact to which all the guilds belonged.

When he told me the idea, I was excited. It seemed like a clean, clear way to give each color combination its own identity. I liked it so much that I suggested we use it as the mechanical heart for the set. A mechanical heart is a key component that you build around to create the structure for the set. If the guilds were our mechanical heart, that meant each guild would have its own flavor identity and its own mechanical identity. The low-hanging fruit was to assign one keyword or ability word mechanic to each guild. That would mean that only those two colors have access to it. The crisscrossing of guilds (i.e., every guild overlapping with the six others) would mean that each guild could have access to seven of the ten keyword or ability word mechanics. Then to show how the guilds are similar yet different, we would make ten-card cycles that run through all ten guilds.

Magic had done factions before, but always monocolor ones. Fallen Empires, the first faction set, had ten factions, two per color. Each faction had a mechanical identity (some more pronounced than others) but no named keywords. Later sets would either have factions that were more story influenced and didn't show up much in the mechanics (for example, Mirage) or factions tied closely to a mechanic, but only a portion of the set (such as the Rebels and Mercenaries in Mercadian Masques).

Ravnica introduced the idea of tying whole draft archetypes to factions. If, for example, you drafted nothing but cards that shared specific guild watermarks (I'll talk more about watermarks next week), you'd have a viable deck. This then gave us a set where every component of the set was part of the larger factioning. In short, it created what we now refer to as a "faction set." This proved to be a very potent tool.

First, it created an identity for each faction with which players could identify. The concept of naming the two-color pairs was so powerful that it became vocabulary for the larger game. Even if your blue and red deck had zero cards in it from the Ravnica block, players would still refer to it as an Izzet deck. The Prerelease allowed players to choose which guild they wanted to play. We ended up making tests for players to take to identify what guild they were. We made shirts, card sleeves, and buttons. It allowed the players to interact with the set in whole new way, one that allowed them to express something about themselves.

Second, it created a new kind of set structure. Mechanics were tightly segmented, and each faction had to play nicely with the factions sharing its colors. It forced us to look for a different type of mechanic. Rather than a larger, flexible mechanic that needed to fill 20 to 30 cards, a faction set wanted smaller mechanics that could go on 8 to 12 cards. This opened it up to a variety of mechanics. The interconnectivity between the mechanics also forced us to craft themes that had higher synergy. You couldn't just build a theme in a vacuum; you had to think about how each mechanic played with the others.

Third, the factions allowed us to rethink how we put a set together, which allowed us to do something else radical, but more on that next week.

Factioning turned out to be so popular that it became a major new tool in our arsenal. Not only did we regularly return to Ravnica, but we made other color-based faction sets. Shards of Alara and Streets of New Capenna had three-color arcs, and Khans of Tarkir had three-color wedges. We created other faction sets built around two colors (Dragons of Tarkir, Strixhaven: School of Mages, Unstable). It shaped how we tackled other themes such as typal (Lorwyn, Innistrad, Ixalan). As we do future planning, we actively think about how often we want to do faction sets. It's a core part of modern Magic design technology.

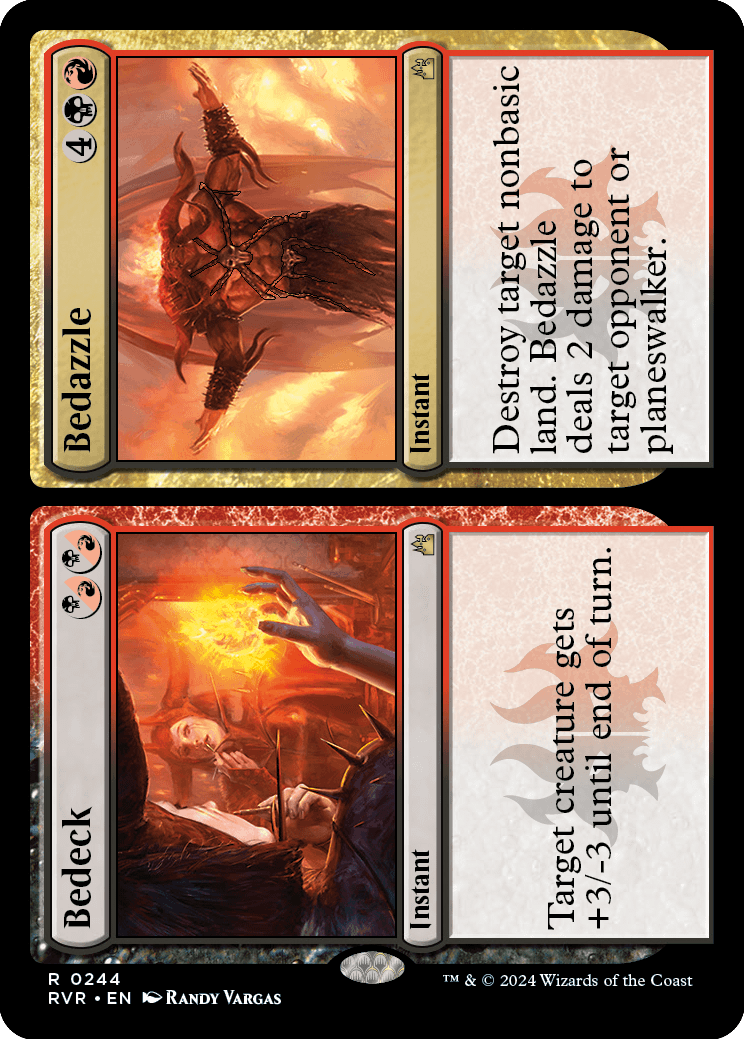

Time to Bedazzle You

Before I go for today, I promised you a card preview from Ravnica Remastered.

-

Click here to see Bedeck // Bedazzle

-

Bedeck // Bedazzle Split cards didn't premiere in a Ravnica set. They were originally created for Unglued 2, which was never released, and we eventually put them into Invasion. We ended up bringing them back for Dissension, the last set in the original Ravnica block, to give all ten color pairs a few extra cards (it was the first time we'd made gold split cards). When split cards premiered and for many returns after, the naming convention was to give them two names that had a ______ and ______ expression. We made enough split cards, though, that we ran out of good names in that model, so in Guilds of Ravnica and Ravnica Allegiance, we tried a new naming convention where both names start with the same three letters.

The Sights of the City

That's all the time I have for today. Original Ravnica had more innovations, which I'll talk about next week. As always, I'm eager to hear your feedback on today's article, on original Ravnica, or any of the aspects of Ravnica I talked about today. You can email me or contact me through any of my social media accounts (X [formerly Twitter], Tumblr, Instagram, and TikTok).

Join me next week for part two.

Until then, may you revisit all the fun of Ravnica in Ravnica Remastered.