Starting with a Good Foundations, Part 1

Hello, and welcome to the first week of Magic: The Gathering Foundations previews. Today and next week, I'll talk a bit about the history of introductory Magic products, introduce the Foundations Set Design team, tell the story of Foundations's design, explain the full suite of Foundations products, and show off two card previews, one reprint and one new-to-Magic card. That's a lot, so let's get started.

"Your greatest weakness is your greatest strength pushed too far" is a favorite saying of mine. Magic's strength is its depth. Magic offers you over 27,000 unique cards to choose from. That depth provides customizability, variance, and strategy. It keeps the game from getting boring because there's always something else to explore. But the depth comes at a cost, what we in design call a "barrier to entry."

A barrier to entry is how hard it is for someone who knows nothing about the game to learn it. How long does it take to go from absolutely no knowledge of a game to enough knowledge to play it? I'm not talking about being good at a game, just knowing enough that you can play it. Here are the core things we've learned people need to know:

The concept of what a trading card game is

Most games come with all the components you need. When you open a Monopoly box, for example, you get the board, the cards, the "money," and the game pieces. That's everything you need to play. If you go to your friend's house and play with their copy of Monopoly, you'll encounter the same pieces. For most people, that's how a game works. The idea that Magic is bigger than a box, where you collect some of the game pieces and choose which ones to play with, is a radical idea, and that's something we have to get across to players early on.

The basic card types

A new player doesn't need to know every card type, but in their first game, we need to at least expose them to lands, creatures, and sorceries. Instants, artifacts, and enchantments shouldn't be too far behind. We can take our time with planeswalkers, and there's no need to rush into battles or kindreds.

The basic zones

We need players to understand their library, hand, graveyard, and the battlefield. We can take our time to get to the exile zone, a little more time to get to the stack, and the command zone isn't necessary until you teach someone about Commander. Most of the core zones are made easier to understand through a player's knowledge of other card games.

How lands work and how spells are cast

This is a crucial one, and one of the hardest to teach, as it doesn't come intuitively for most players. The key to teaching this aspect of Magic is getting them to see the connection between lands and the mana costs of spells.

The five colors of Magic

The five colors are, interestingly, the opposite of spell casting. Players understand it easily, but it's not integral to learning how to play, other than understanding how colors in mana costs work. The reason you want to introduce it early on is because it's one of the most-compelling elements of the game.

The steps of a turn

This involves learning the order and process of untapping, drawing a card, playing your cards, and attacking. The player doesn't need to know all the details, such as what's a step and what's a phase, but we do want them to get a sense of the organic flow of a turn. When things tap or untap is another common pain point for beginners.

How attacking and damage works

This is the third area where new players struggle. They really want their creatures to attack their opponent's creatures, not their opponent. You don't need to get into most of the details, but you do want them to understand how creatures make the game end and the basics of attacking and blocking.

If you can master these components, you'll know enough to play Magic with a little bit of guidance.

Beyond the complexity of a game's components lies another major question: How intimidating is the game for new players to learn? Chess, for example, isn't that difficult to learn. It has six unique pieces, and the basic rules fit on a sheet of paper. But there's a lot more to a game than just the nuts and bolts of how to play. Designers have to think about how people who don't play the game perceive the game. Chess is thought of as this highly intellectual game, which makes learning it intimidating.

Magic is both complicated and intimidating. Over 30 years of cards and a comprehensive rules book that is inches thick makes learning it pretty daunting. At the time of this article being published, I just celebrated my 29th anniversary working at Wizards of the Coast in Magic R&D. For all those years, we have been trying to figure out how best to teach new players. It's a challenging task, a fact that's made clear by how hard it's been to do well.

When I first got to Wizards, we tried something called the ARC system.

The idea behind it was that it was a simplified version of Magic. There were just three colors rather than five and just four different card types: the equivalent of land, creatures, sorceries, and instants (though they could only be cast during combat). We made three different versions of it. One had an original story made by famous comic artist Jim Lee called C-23. The others were based on television shows: Hercules and Xena: Warrior Princess. This was our earliest stab at something like Universes Beyond.

When the ARC system failed, our next attempt was something we called Portal. It was another attempt at a simplified version of Magic, but this time a little closer to the actual game. Portal used all five colors, complete with the Magic mana symbols, and had card with the Magic card back. Some of the cards were even reprints from existing Magic sets. The Portal cards were designed so they could be shuffled into a normal deck and work, but the core of Portal was a simplified version of Magic. There were only three cards types: land, creature, and sorcery, although some of the sorceries acted like instants. Some of the terminology was changed. Blocking, as an example, was called intercepting.

While all the cards could work in a Magic deck, the new cards weren't legal in any Constructed format, creating a divide between Portal players and Magic players. Years later, we would make all Portal cards Eternal legal. There were three Portal sets: Portal, Portal Second Age, and Portal Three Kingdoms, the last of which was designed for the Asian market and based on a famous historical novel called Romance of the Three Kingdoms. Among other things, the set is famous for changing flying into an ability called horsemanship.

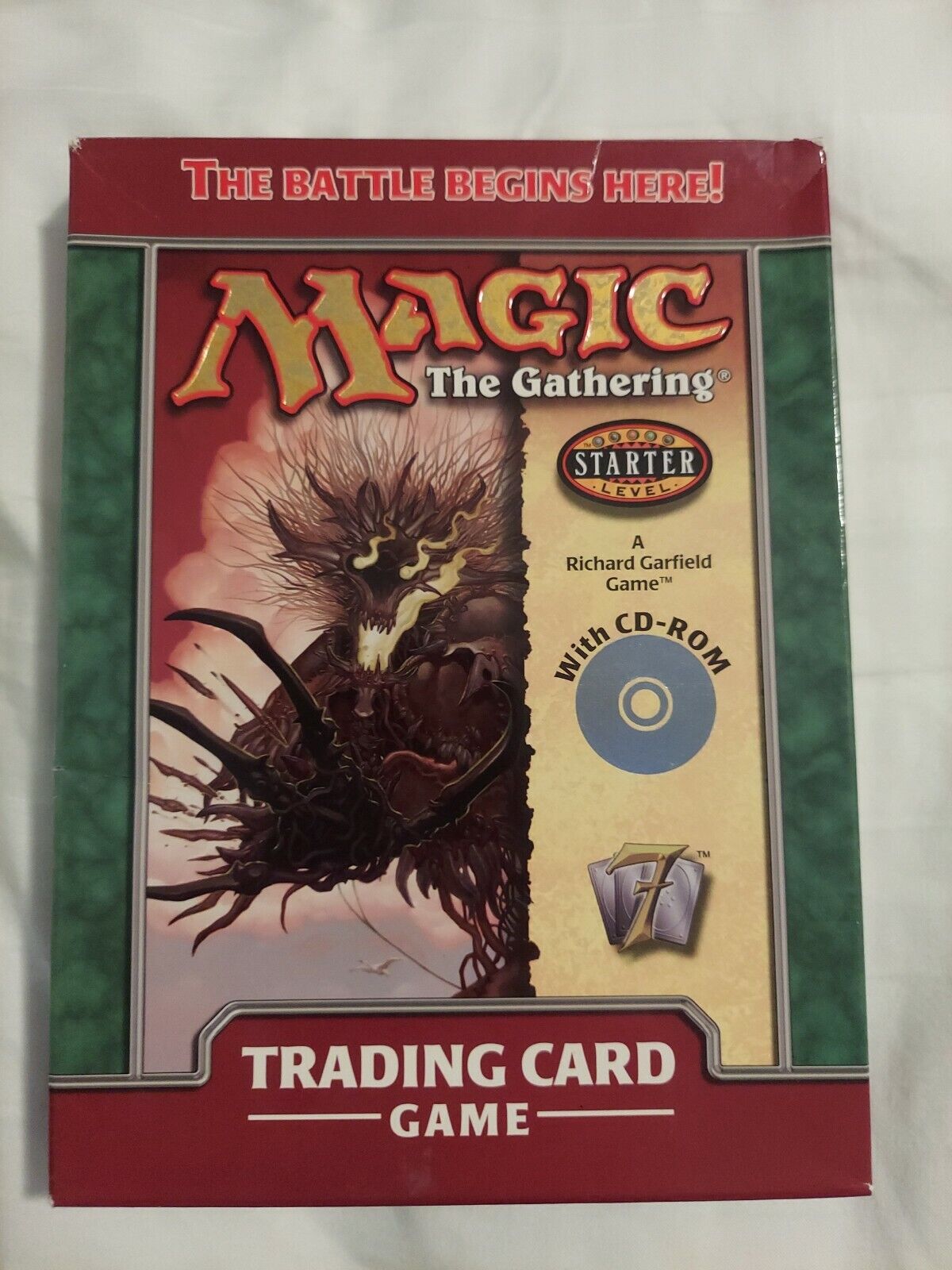

The next attempt at a beginner product was called Starter. Rather than being a separate product with different terminology, Starter was a subset of Magic cards, albeit ones that focused on the simpler side of the game. There were lands, creatures, sorceries, and a small sampling of instants. Creatures had some evergreen abilities but no tap abilities. Starter had a boxed product that acted as a tutorial as well as randomized boosters. I believe this is the first product that adopted the idea of a turn-by-turn tutorial. Both players are given decks in a specific order and were then taught by a booklet that walked them through each turn of the prearranged game. This turn-by-turn tutorial was one of our biggest discoveries in how to teach Magic. There were two different Starter products: Starter 1999 and Starter 2000.

Beginning with Seventh Edition, the Starter Box was incorporated into core sets. In addition to the normal first-game tutorial, Seventh Edition came with a CD-ROM that allowed you to play one of the decks against the other. One of my jobs for Seventh Edition was to write the logic behind the code of how the computer played its deck. I prioritized what order the computer should play its cards and then walked through the logic of what order the computer would make use of the cards. For example, if the card was going to destroy a creature, I gave the program a priority list of what to destroy. It wasn't exactly modern AI, but it did a good job of giving a beginner a fun game. The CD-ROM allowed a new player to play for a while by themselves, figuring out basic strategies at their own pace, before playing with other people. In later years, this would morph into digital tutorials.

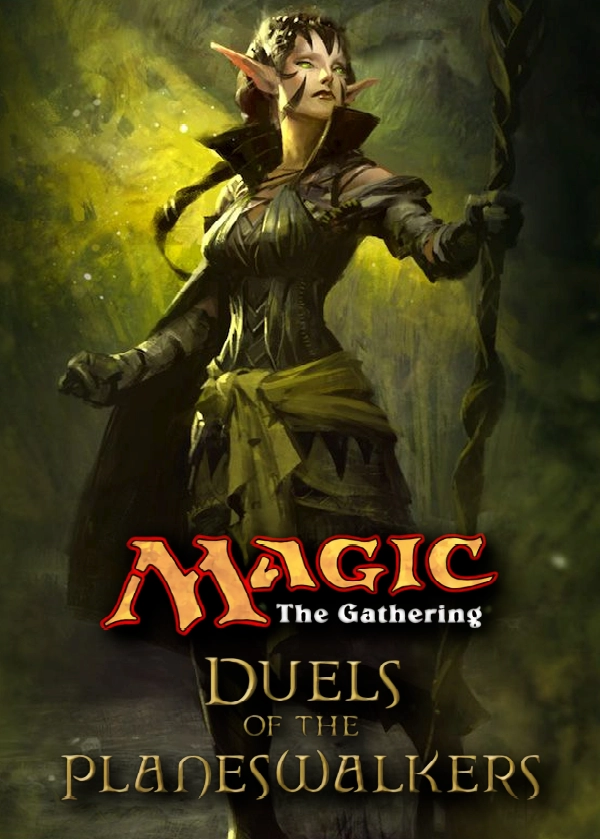

We tried numerous things with various core sets and starter products over the years. We experimented with different layouts for our teaching manuals. Pictures, perhaps unsurprisingly, turned out to be instrumental. We tried different preconstructed decks. We used various mediums to teach, including incorporating more digital teaching tools. The biggest leap forward in this area was a video game called Duels of the Planeswalkers. It released in 2009 for video game consoles and demonstrated some of the huge advantages that digital methods had for teaching Magic.

It allowed a player to learn at their own pace, gave them the ability to have more control of how they learned, and most importantly, let them learn without another human judging them. The computer was patient and kept to itself if you took a while learning something new. Also, the fact that it was available on consoles let people play on their televisions in the comfort of their home.

The next big leap in teaching technology was Jumpstart. Jumpstart started as a hackathon project run by Doug Beyer. The impetus behind it was to find a way to make deck construction simpler. One of the things we'd learned over the years was that a major barrier to learning Magic was deck building. We could make preconstructed decks, but our goal was to find a way to let players have some input into deck building without it being too onerous. Doug's pitch (based on various ideas that had been explored) was a system where you had the choice between a variety of half-decks. You could choose any two and they would go together to make a deck.

While simple in concept, this idea proved to be a lot more complex in execution. How exactly do you make a bunch of half-decks that all go together, especially when each half-deck has its own mechanical theme? Even once we figured out the mechanics of it all, figuring out how to print such a product was a huge undertaking. It also required us to work with our printers to do things we'd never done before.

The original Jumpstart set came out in 2020 and was a big hit. We followed it up two years later with Jumpstart 2022.

I bring up all this history because this is the information that led us to create Foundations.

Before I get into how we made Foundations, let me first introduce the designers who made it. Since Foundations was modeled after core sets, it didn't have a vision design, moving straight into set design. As always, I'll let the lead designer of the team, Bryan Hawley, introduce the team members. Don't let him writing about himself in third person fool you.

-

Click here to meet the Foundations Set Design team

-

Foundations is a set with so much enthusiasm behind it in design. It was crucial that we get a variety of perspectives on the set, so there were more designers during Foundations's design period than there would normally be for a design that only ran for one year. Each designer brought a different perspective and expertise.

Bryan Hawley was the lead set designer for Magic: The Gathering Foundations and helped orchestrate the rest of the interconnected pieces of the product suite. His day job is as a game design director for Magic, though he moonlights as a set design lead from time to time, most recently leading the last few Masters sets.

Carmen Klomparens is a powerhouse senior game designer on the play design team and wore a lot of hats for Foundations. She was a strong second for the main set, heading up most of the play design work for both Limited and Constructed late in the process, and was the lead designer for the Foundations Starter Collection.

Matt Tabak is a principal editor, R&D's resident MC, and one of the linchpins of Foundations. As an editor, he was instrumental on the Foundations Beginner Box tutorial, writing and rewriting copy for the tutorial, and he spent several months on the Set Design team early on.

Reggie Valk is a versatile, adaptable generalist senior designer across a variety of sets and product types, including experiences like Ravnica: Clue Edition. He is our resident Jumpstart expert. He was lead set designer for Foundations Jumpstart and led the design of the gameplay and packets of the Foundations Beginner Box beyond the tutorial sequence, as well as helping out on the main set.

Daniel Xu is one of the newer designers on Magic, and one of the brightest. He contributed to every aspect of the main set. Across cards, mechanics, reprints, overall design, his fingerprints are everywhere.

Jeremy Geist is a brilliant vision designer and served on the Set Design team for the first few months while Foundations was taking shape. He's one of our most prolific and clever individual card designers, and his background in casual and party game design brought a valuable viewpoint to a set focused on being exciting and fun with as low of a barrier to entry as possible.

Adam Prosak is a veteran senior game designer who's led the design of many sets over the years, most recently Phyrexia: All Will Be One. He's particularly passionate about casual gameplay and teaching. He helped guide the shape of the set as it came together in the early stages

Annie Sardelis is a senior designer who was on the team for only two months, but the focus on charm and simple delight that she infused into the cards and the team's thinking in that short time was great!

Doug Beyer is a creative director and was the worldbuilding lead early on during Foundations design while we established the tone for the set and which characters to focus on. He spent a few months on the Set Design team contributing cards and archetype ideas. Fun fact: his catchphrase for the set, one he said so many times we started joking about it, was about its "implication of tantalizing depth."

Foundations began as an old idea. For years, dating back to my early days at Wizards, we'd talked about the idea of a core set that didn't change. We used to call it the ultimate base set. We never actually made it, but the idea of a constant core set would come up as a product concept every few years. One day, Aaron Forsythe and some of his direct reports were talking about what was going to go in the final product slot of 2024.

There were a lot of issues swirling about. We'd be trying to figure out a product to help new players get into the game. We'd been examining ways to cut back on the number of Magic releases. We were trying to figure out how to best position a new Jumpstart set. As they talked it through, they realized there was a product to address all these issues. The unchanging core set, the one we've been talking about making forever.

"What if we finally just made it?" asked Aaron.

Magic has gone back and forth on having a core set. We like it as a landing point for new players, but a constant churn of new core sets proved problematic. For example, because the core set kept changing, we had to keep adapting it to Standard and Standard to it. If we just made a single product that didn't change, we could build around it and give the entry-level product a consistent identity. By having the core set not be something that's grabbing attention every year, it's one less thing established players have to focus on. That would also allow new players to enter the game with a constant reference point.

Once we decided we were going to make it, the next big question was what we would include. Bryan and his Set Design team decided that they needed to start by looking back and seeing what we've learned from our last 30 years of teaching beginners. There were two big takeaways, which I will talk about next week as we're out of time for today.

But before I go, I have two preview cards to show you. One is a popular reprint, and the other is a brand-new card.

Let's start with the reprint.

I'll give you some clues about it. When you think you know what it is, click the box below.

Clue 1: I designed this card many years ago.

Clue 2: It does something that I've always been a fan of, but it took R&D a while to warm up to.

Clue 3: It's a popular mechanical theme with the players, one R&D has been doing a lot more of recently.

Clue 4: It premiered in Ravnica: City of Guilds.

Clue 5: It's a green card.

-

Click here to see the card

-

0216_MTGFDN_MainRep: Doubling Season 0428_MTGFDN_JapanSh: Doubling Season 0438_MTGFDN_FFJpnSho: Doubling Season Yes, it's

Doubling Season . As a Magic designer, most of what you design is for other players, but every once in a while, you get to make a card just for yourself, something you, as a player, enjoy. I'd always loved doubling effects, and Doubling Season was just a love letter to the theme. It was a card I knew I would love playing with.Well, it turns out a lot of players also enjoy doubling, and the card has gone on to be a fan-favorite design. It is such a beloved card that we decided to bring it back to Standard and put it in Foundations.

My second card preview is a new-to-Magic card called Sphinx of Forgotten Lore.

-

Click here to see Sphinx of Forgotten Lore

-

0051_MTGFDN_MainNew: Sphinx of Forgotten Lore 0457_MTGFDN_ExtRM: Sphinx of Forgotten Lore 0314_MTGFDN_BrdFaves: Sphinx of Forgotten Lore 0380_MTGFDN_EclBdFav: Sphinx of Forgotten Lore As I'll talk about next week, Foundations has a number of deciduous mechanics in it. This card showcases flashback, a mechanic I first made back in Odyssey. A Sphinx that grants flashback to instants and sorceries as an attack trigger felt like a natural tie to a Sphinx, since it is a mystical creature all about knowledge. I hope you all enjoy playing it.

Applying a Foundations

That's all the time I have for today. I hope you all enjoyed part one of my look at Foundations. As always, if you have any feedback on the article, or any part of Foundations, you can email me or contact me through any of my social media accounts (X, Tumblr, Instagram, and TikTok) with feedback.

Join me next week for part two.

Until then, may you find friends that you might enjoy introducing to Magic.