Avacyn-gle Ladies, Part 3

Welcome to Pro Tour Avacyn Restored Week. This week, the site will be talking all about Avacyn Restored and the Pro Tour that will use it. To keep in tradition with my last Pro Tour theme week, I'll be doing the third part of a three-part article of card-by-card stories of the set. Go read Part 1 and Part 2 first if you haven't yet.

I have an interesting relationship with the exile zone. So much so that I even made a card in Unhinged to vent my frustration.

Before it was called exile, the zone was called the "removed from the game" zone. The problem was that being removed from the game didn't actually mean that. Note that there are two main ways we use the exile zone. One is as a hiatus, to put things that might very well come back because the thing that removed it plans to possibly bring it back.

For example, Oblivion Ring wants to get its target out of the game for as long as Oblivion Ring is in the game. Once Oblivion Ring is destroyed, though, the permanent it's removing needs to return. Now, I like many of the cards that temporarily exile things, and I have no problem with making them. In fact, I actually like making cards like this. Even this use makes the term "remove from the game" a little sketchy, as at best you could argue it is "temporarily removed from the game." I was happy when we changed the term to "exile."

The second use for exile is that the game needs ways to remove something in a way that it's gone for good. Some of this is a mechanic need—we really only want a card used once, for example, or we want a card eliminated so there is no way it can be brought back. Some of it is flavor. Swords to Plowshares was all about saying that white can remove threats without killing them. If you never got it, Swords to Plowshares removes the creature's desire to fight, so it leaves to go do less warlike things.

The inertia of Magic design is to do things that have never been done before. So obviously, the idea of getting things back from the zone that normally you can't get things back from is attractive. Here's the problem: the game needs a way to permanently get rid of things. The more we allow things to get back exiled cards the more we turn the exile zone into graveyard #2. At some point, it could even force us to make a new exile zone. That whole idea is ridiculous, as there's no need for graveyard #2. We have graveyard #1 doing lots of good work. If we want to allow you to get things back, let's put our energy there.

Because of all this I have campaigned pretty hard to stop getting things back from exile. I feel my job as head designer is to fight this kind of design inertia to make sure that we don't ruin things because we don't have the self-control to not ruin them. I bring all of this up because Misthollow Griffin plays around in this space.

Be aware, the reason I've come to terms with this card (and note I did fight to stop us making it) is that, really, it's in the first group of cards, which I'm fine with. The problem is that it seems like it's in the second, and I don't want to further slide down the slippery slope, because it feels like we've allowed ourselves to get more things back from exile.

All this is a long way of saying that I have mixed feelings about this card. I feel it's awesome that Ramp;D as a group isn't defined by the thoughts and opinions of any one person. It allows us to create the game in a way that one single visionary never could, but it does mean there are cards like this that make me personally twitch a little. (My mantra for this card is "At least it's not Hornet Sting.")

So Avacyn Restored needed basic land. Every large set has basic land. This was a large set, though, that would restart the draft environment, so we wanted new art for them. The problem, though, was that although the tone of the set has changed radically from the two other sets in the block, the actual geography had not.

The solution was an elegant one. Let the artists of the Avacyn Restored basic lands go back and show the same scenes from the Innistrad basic land but now with a lighter, less ominous feel. How do we show the change on Innistrad? Through the contrast of the basic lands. If you want to see more of this, check out this Magic Arcana.

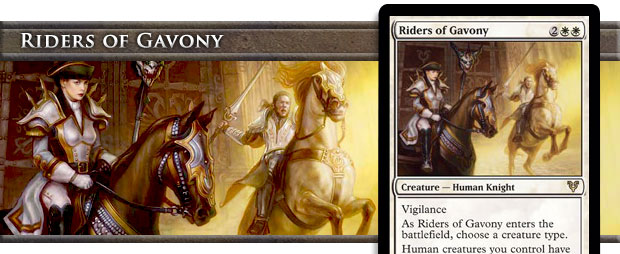

This card solved an interesting design problem. We wanted the flavor of the humans driving out the monsters. The problem, though, was that Avacyn Restored was being drafted by itself and the change in the tone of the set meant there were a lot fewer monster cards in the set. By letting the card name a creature type, it had the flavor we wanted and allowed players in Constructed to use this card as an answer to tribal-themed monster decks. In Limited though, you can use it however you need to, meaning you can name things like Angels and Humans. The fact that you name it allows needed functionality while keeping the flavor.

Here's a common problem we have in design. You have some neat iconic part of the set that you want to make super splashy and cool. This tends to lead you to design one or more mythic rare cards, but I keep talking about how we want your themes brought down to common so we make sure all the players actually see them.

Case in point for this set: Avacyn and Griselbrand. Clearly, these legendary creatures wanted to be mythic rares, but how do we make sure the guy who buys ten packs has a chance of ever hearing of them? Okay, in Avacyn's case we went the distance and put her in the name of the set. Hopefully, that gets the job done for her, but what about Griselbrand?

The trick to solving this problem is to create things associated with the legendary creatures in question. Sometimes these cards can be spells, and sometimes they are creatures or enchantments or lands. Often, they're artifacts, as flavor loves concrete items.

The scrolls were designed for multiple reasons. One was to show contrast between the forces of good and the forces of evil. Note that the mechanics mirror each other to create this sense of conflict. Another important reason to do them is because we want to create associations with our main characters. We want to get their names on common cards and we want to help associate a feel with each character.

Avacyn likes angels and wants to help you. Griselbrand likes demons and likes hurting people—in this case, your opponent. These cards might seem very innocuous but they are doing very important work communicating the major themes of the set.

The number one comment with Tamiyo I've received is, "She doesn't feel like she belongs in this block." My response is that what people are really saying is, "She doesn't seem to fit in this world." My response to this is, "Exactly. That's the point."

It's very easy to gloss over what a Planeswalker is because we don't play up their Planeswalkerness as much as we could. Mostly you just see the Planeswalkers on the cards. They're just here—wherever here may be. What gets forgotten is how they got here.

It's very easy to think of Planeswalkers as just a fancy way to say wizards or mages but it misses a key defining point. What exactly is a Planeswalker in the world of Magic? The answer is that Planeswalkers all share but one trait. A Planeswalker has the ability to walk between planes. This might sound silly, but the concept is very important.

Almost everyone who lives in the Multiverse has no idea of its existence. They live on a plane and for all they know that is what exists. Planeswalkers, though, have a special ability (what we call "a spark") that allows them to travel between these planes. That sole ability is what defines Planeswalkers. They are a special lot because they have learned a major fact about the Multiverse no one else knows.

I bring this up because one of the things we don't do that often is play up the fact that Planeswalkers normally aren't from the plane we see them in. The question to me isn't "Why does Tamiyo seem out of place?" but rather "Why don't more Planeswalkers seem out of place?" I think Tamiyo is paving new ground as a means for how we make Planeswalkers. For example, there are many more worlds we've visited than ones we can return to, so using Planeswalkers as a means to tip our hat to them might be something we want to do more.

A lot of that, though, is going to depend on how Tamiyo is received. If players like having a Planeswalker clearly from a plane of Magic's past, perhaps we'll do more. I know I'd like to see more Planeswalkers who feel like they come from somewhere else.

I've done a lot of interviews for Avacyn Restored. In just about all of them I'm asked what my favorite card is from the set. In each one, I say Thatcher Revolt. Why, you might ask? The card is not at all splashy and doesn't even seem on the surface like it has much to do with Avacyn Restored. This is the Angel set. Why am I enamored with three angry farmhands?

For starters, let's talk about what Avacyn Restored is really about. It's about the tide turning in the world of Innistrad. Sure, the angel Avacyn has returned, but the bigger story is the impact her return has had. I've talked in this column before how I see humans as the protagonists of Innistrad block. The story told is their story.

Riot Ringleader | Art by Gabor Szikszai

In Innistrad, the humans are in trouble. Monsters surround them on all sides and the tools that have been keeping them at bay are getting weaker and weaker. In Dark Ascension, the humans are on the cusp of extinction. Things had never been bleaker. Avacyn Restored shows the humans' triumphant return. The set is about seeing the humans reclaim their world. In that context, Thatcher Revolt is very much about what Avacyn Restored is. Yeah, they're angry. The humans have been through a lot.

But that isn't the real reason Thatcher Revolt is my favorite card. Usually, the cards that are the most popular with players are the cards that are splashy, with big effects on the game or powerful in the effect they create. Designers, on the other hand, are attracted to slightly different things. Designers love elegance. Designers love simplicity. Designers love cards that help tie everything together.

That's why I love Thatcher Revolt. It's such an elegant and simple card yet it does so much. Whenever I've said this, the reply I keep getting is: "I don't see it." Let me explain.

I talked a few weeks ago about how we wanted to create contrasts between the sides of good and evil. The good side had enter-the-battlefield effects. The evil side has death triggers (aka things that trigger when they die). To help promote those mechanical themes, the good guys have numerous cards that reward creatures entering the battlefield and the bad guys have cards that reward things dying. Thatcher Revolt does both.

In fact, there was a fight for what tokens Thatcher Revolt was supposed to make. The card worked so well with both sides that each deck wanted its creature type (Human or Devil) mentioned. In the end, because the humans won and thus make up more of the set, and Human tribal mattered more, Human won out.

If you managed to get to the Prerelease last week, hopefully you've started to get a sense of the set's synergies and why Thatcher Revolt is a figurative Swiss Army Knife for the set's Limited. If not, you soon will.

Now we get to the other Planeswalker of Avacyn Restored. The number one question I've been getting on Tibalt is, "Why does the discard have to be random?" The answer is because it would be too strong if it wasn't random. Development decided it wanted to try and make a two-mana Planeswalker, so that meant putting a lot of restrictions on the card.

Why did Tibalt have to be two mana? One of the challenges of making Planeswalkers is trying to give each of them their own identity. One way to do this is to look for different areas that no previous Planeswalker has covered. That's how we got to a two-mana Planeswalker. The development team is willing to push cards and take risks, but a two-drop Planeswalker seemed to be a poor place to take such a risk, as the downside far outweighs the upside.

The number two question about Tibalt I've received is, "Was he named after the character from Romeo amp; Juliet?" I don't think he was, although many of us were aware of the name because of Romeo amp; Juliet. In fact, Tibalt's name (which is spelled differently; the character in the play was Tybalt) has spawned numerous Romeo amp; Juliet jokes. My favorite, created by Shakespeare fan and Magic card designer Shawn Main, is that any creature that kills Tibalt is exiled.

The funniest thing about this card is that it's poking a small joke at Ramp;D. For those of you who are unaware, we refer to the giant series of desks where Magic Ramp;D works as the Pit. (My daily comic, Tales from the Pit, is named after it.) We also refer to people who sit in the pit as Pit Dwellers, so this name is a bit of an inside joke.

Mechanically, the interesting thing about it is that it does something designers love to do. It takes a mechanic and finds a way to invert how it normally works. You see, with most undying creatures you want them to die because they come back stronger, but Treacherous Pit-Dweller is the undying card where undying is a drawback, not an upside mechanic. I don't like to do too many of these kinds of cards but one or two a set is usually fine.

I've talked previously about how we decided to make green the best color for soulbond. One of the ways we did this was to put all the power-boosting soulbond cards in green. Why does this matter? Because the power-boosting cards have a very unique quality among soulbond cards. They are the only ones where you are encouraged to pair them with themselves.

Usually, you don't want to pair the same creature with itself because having the same ability twice doesn't do anything extra. But power-boosting stacks, so it does work. Remember, if you pair a Trusted Forcemage with another Trusted Forcemage both become 4/4 creatures.

This is what Ramp;D calls a "punisher card." That is, the card gives the opponent two choices to pick from, and either choice is a punishment because it does something bad for your opponent or something good for you. Usually, one of the choices is direct damage to the opponent.

I made the original punisher cards in Odyssey because I was trying to find different ways to give red the feeling of chaos. I liked the idea that these were spells that allowed red to stretch what it could do (usually one of the punisher cards in Odyssey block did something out of color pie for red) but didn't allow it the control to what was going to happen.

The punisher cards went over very well. So much so that we've pulled them out from time to time. Vexing Devil has not bucked this trend and initial response to Vexing Devil has been very strong.

So we wanted a creature that was more offensive than defensive. We talked about a bunch of different ways to do it when we stumbled upon this simple design. What if we just made it bigger when you are able to attack? I like that this card hints at what it wants without bluntly telling you. There is a time and a place for cards to be blunt, but I like the fact that sometimes the cards get to be a little subtler with their intent. The mechanics themselves push you in the right direction without having to loudly tell you that's what it's doing.

I have talked numerous times about the weekly Tuesday Magic meetings, but I've spent far less time talking about an equally important Tuesday meeting about Magic. The meeting is called Card Crafting, and it is a chance for the core designers and developers to get together and talk through technical issues. For example, this was the meeting where we figured out how we were going to separate blue looting from red looting.

One of the topics we had a few months ago was how to differentiate white's growth effects from green's. By growth effect I'm talking about things like Giant Growth—usually instants that boost a creature's power and toughness until end of the turn. Both green and white can do these boosts, but we wanted to make sure they weren't doing the same thing.

What we decided in the meeting was the following:

Green gets big boosts while white gets small boosts

The first dividing line we made was what I'll call the Giant Growth line. We decided that +3/+3 and larger boosts were supposed to be green. White's boosts are allowed to be no larger than +2/+2. We did allow green on special occasions to do +1/+1 and +2/+2, but those would be special exceptions and not the norm. Usually, those smaller boosts would be accompanied by other things on the card.

We also decided this line would be used for mass boosting, which white and green also do. White would be able to boost its team for +1/+1 or +2/+2, but once it got up to +3/+3 that was more green's area.

White gets abilities with its pumping

One of the ways to separate the two was to allow white to do a little more than just boosting power and toughness. As such, most of white's boosting also grants keyword abilities. Zealous Strike is an example of a white boosting card with this feel. Green got the one exception that it is still allowed to grant trample in addition to its boosts every once in a while.

These little details might sound silly, but it's actually key to the game's wellbeing. The color pie is vital to Magic's health, so one of the things we must always be vigilant about is ways to make sure each color has clear definition, even when two colors do similar things.

- "And That's The Way It Was"

I hope you've enjoyed this three-week jaunt through the cards of Avacyn Restored. I'm eager to hear your feedback about what kind of stories you liked and didn't like to shape future card-by-card story columns. (They're pretty much a staple at this point.) You can talk to me through Twitter, Tumblr, and Google+, this column's thread, or my email.

Join me next week when I bond with a bunch of creatures.

Until then, may people enjoy listening to your stories.