The Basics of Mana

For the next few weeks, Reid is revisiting some of the key concepts of Magic, updated for Magic Origins. These concepts are so important to learning Magic that we wanted to reintroduce them to the next wave of Magic players. Enjoy.

Nearly every game of Magic begins the same way: a player plays a land. Mana is one of the fundamental resources of Magic. Without it, you simply can't play the game.

Mana is central to the game play of Magic, but its importance begins even before we reach that point. Mana is also one of the key elements of deck building. In the same way that you can't cast a spell without the proper mana in a game, you can only put creatures and spells in your deck if your mana base can support them.

The Mana Base

A deck's mana base is its lands and any supplemental ways to produce mana, such as anything along the lines of Leaf Gilder or Nissa's Pilgrimage. A mana base can be simple (say, seventeen Plains in a mono-white Limited deck) or it can be quite complex: featuring multiple colors of mana, lands with unusual abilities, and indirect methods of making mana (via artifacts, creatures, or spells).

There are no hard and fast rules about what a mana base should look like; any guidelines I can offer might need to be adjusted or completely scrapped under certain circumstances. However, what I can give you is a helpful starting point.

How Many Lands to Play

Traditional knowledge is that lands should make up a touch over 40% of a deck. This means about 17–18 lands for a 40-card deck and about 24–25 lands for a 60-card deck. This is a tried-and-true structure that's worked for many players for many years. You'll rarely be making a big mistake if you always stick to such a guideline. That said, there are a number of factors that might make you consider small adjustments.

Consider if you have any nonland ways to produce mana. The presence of creatures like Leaf Gilder might impact the number of lands your deck needs to function.

The correlation isn't one-to-one—as in thinking one Leaf Gilder equals one land—for a number of reasons. First, you cannot cast it unless you have lands already. Second, Leaf Gilder is less reliable than a land because it's easier for your opponent to kill. Third, you'd normally put such a card in your deck because you're looking to jump ahead in mana, but you still want to play a land every turn, at least for the first few turns. These cards shouldn't be counted directly as lands, but two copies of Lead Gilder can be a fine reason to play, say, seventeen lands instead of eighteen in your Limited deck.

An equally important question is, simply, how expensive are the cards in your deck? If all of your spells cost four mana or less, you won't need as many lands as a player sporting multiple cards that cost seven or eight mana.

Colored Mana

A question that can be even more challenging is how to balance your colored mana requirements. There's not much to it if you're only playing one color, but once you get into the realm of playing three or more colors, things get a little hairy.

Often in Magic, you'll be presented with small tradeoffs between power and consistency. The more colors you play, the wider the range of cards you have access to. So it's likely that your deck will be capable of more powerful draws when everything runs smoothly. However, when you play more colors, it also becomes more likely that you'll be stuck without the proper colors of mana to play one of your spells, which will lower the consistency (or reliability) of how your deck functions.

Finding the right balance of power and consistency can be tricky. When it comes to a mana base, one important question is: What tools do you have access to?

In the simplest case, you'll only have basic lands (Plains, Island, Swamp, Mountain, and Forest) to work with.

When you're working with basic lands, a two-color deck is virtually always where you'll strike the right balance between power and consistency. If you only want to play one color, that's a perfectly fine choice, but if there's an appealing card that you'd like to play in a second color, you can feel safe in doing so. With two colors, you'll be able to cast both colors of spells in most games (not all games, but what most players would consider "an acceptably high" percentage of games). With more than two, you'll begin to notice problems.

However, that's a description of the simplest case. A deck builder is like a carpenter—the better the tools the carpenter has access to, the more complex projects he or she can undertake. Nonbasic lands, as well as nonland ways to produce mana, can be quite powerful and can assist you in playing multiple colors in your deck.

Meteorite, Evolving Wilds, Caves of Koilos, Shivan Reef

If you have access to a bevy of cards like these, which have the ability to produce multiple colors of mana, you can begin to feel comfortable playing a three-color deck if you choose to. Playing with more than three colors is a rather advanced technique; I recommend against it until you feel very comfortable with two- and three-color decks.

Even when playing multiple colors, it can be in your best interest to center your deck primarily around one or two colors, and be a little bit less reliant on the rest. Say, for example, you have a sealed deck that's primarily black and red, but you want to play with two copies of Possessed Skaab. It might be fine to only play with three or four sources of blue mana in your deck. You'll often find a way to make blue mana by the time you're ready to cast Possessed Skaab. And even if you don't, having one card stuck in your hand for a little while isn't a complete catastrophe. This is commonly referred to as splashing a color.

To play a deck equally reliant on all three colors of mana is possible, but difficult. After all, the more things that can go wrong, the less often things will go exactly right. Here are a few more guidelines to use as a starting point:

- For a 40-card deck, if you really want to have a land that produces a certain color of mana in your opening hand, you should play at least nine or ten lands that produce that color (eleven to be safe).

- For a 60-card deck, you should play at least fifteen or sixteen lands that produce that color (seventeen or eighteen to be safe).

The Mana Curve

The question of mana isn't fully answered once you've decided how many and what types of lands to play. It also influences what spells you play with and the overall structure of your deck.

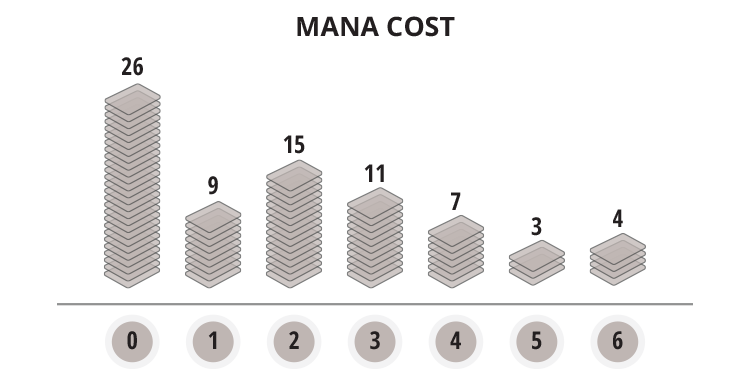

A deck's mana curve is the balance it strikes between cards of varying mana costs—cheap cards and expensive cards. You might refer to a deck as having a "high mana curve" if it has more expensive cards than usual, or a "low mana curve" if it's comprised mostly of cheap cards.

It would be a mistake to play with all cards that cost five mana, because you'd have nothing to play in the first four turns of the game! On the other hand, if your deck was made up entirely of weaker, one-mana spells, you wouldn't be making the best possible play on any turn beyond the first one. There's a lot of value in having at least a couple of cards of each mana cost.

Like most things, the mana curve is not an exact science. There's no "master formula" for how many cards of each mana cost you should play. The answer to that question depends a lot on context. What cards do you have access to? What's your strategy for winning the game? What are your opponents likely to be doing at each point in the game?

The concept of the mana curve is important to all decks, but it's most clearly illustrated in the case of a fast creature deck. If your goal is to play creatures and unload a lot of damage very quickly, you really want to come out of the gates starting on turn one or two. Some Constructed decks play twelve, fourteen, or even more creatures that cost one mana!

Again, this is a question of strategy. If your goal is not to win with a quick creature rush, playing dozens of one- and two-mana creatures will water down your deck and reduce the number of more powerful spells you can play with. You should have some plays that you can make early in the game, but there's no mystical number for how many it should be. Ask yourself how fast your opponents are likely to be. Do you have to start defending yourself immediately on turn one, or might it be okay if you sometimes don't play anything until turn three?

Mana "Hosed" and Mana "Flood"

It's a sad fact, but every new player learns these concepts early in his or her Magic career. "Mana hosed" is one slang term for when you don't draw as many lands as you want, and "mana flood" means that you've drawn far too many. These things can happen to any player, with any deck, at any level of competition—it's simply part of the game.

But not to worry! Although any one particular game where you get mana hosed might be aggravating and unfun, variance in the number of lands you can draw is actually something that enriches Magic and helps to make it the game it is.

There are things you can do to manage being mana hosed and mana flooded, both in deck building and in game play. It all starts with doing a good job of building your mana base and your mana curve, but here are a few other tricks you can use.

To mitigate the risks of mana flood, one thing you can do is look for mana sinks. Mana sinks are cards that, while not necessarily expensive in themselves, can make use of your extra mana in late-game scenarios.

To view the entire cards, check them out in the Card Image Gallery.

Note that it's completely normal to draw eight, nine, or even more lands in the course of a long game. When you have a mana sink in play, you might still prefer to draw more spells, but when you inevitably start drawing more lands than you need, at least you can put them to some use.

If your goal is to mitigate the effects of being mana hosed, you can look for cheap cards that have the ability to answer or trade with more expensive cards.

My best piece of advice is simply to recognize that drawing the wrong number of lands is a normal part of the game. Try your best not to be frustrated by it. A common pitfall for a new player is to overcompensate by adding or removing lands from a deck after every mana hosing or mana flood. If, after a couple of dozen games, you notice a pattern of things working out poorly, it's good to learn from that and be ready to adapt. The point is to not let short-term frustration overcome rational decision-making.

Example

Let's take a look at an example sealed deck, with an eye toward its mana.

To see the new cards from Magic Origins, check them out in the Card Image Gallery.

This deck is mostly red and green, but splashes black for a removal spell (Cruel Revival) and a particularly strong creature (Blazing Hellhound).

The first question is how many lands to play. A typical sealed deck should play with seventeen or eighteen lands. This one looks fairly typical, so there's no reason to deviate from that. It has a handful of expensive cards, costing five and six mana; it has a mana sink in the form of Volcanic Rambler; and it's three colors. These factors would normally make me lean toward playing eighteen lands rather than seventeen.

However, it also has a Leaf Gilder and a Meteorite, each of which can count as a fraction of a land. Also, the presence of two Elvish Visionaries, a cheap card that draws another card, can help this deck find more lands if it gets stuck early in the game. All things considered, I think it's best to go with seventeen.

Next, what about the colored mana? Black is only a splash color, so we want to play enough black mana that we'll usually draw one in a normal game, but there's no need to go far beyond that. Three sources of black mana might work, but four would be ideal. Thankfully, this deck has Meteorite, Evolving Wilds, and Llanowar Wastes to help out! One Swamp (to go with the Evolving Wilds) makes four sources of black mana, which is perfect.

The rest of the deck is pretty evenly split between green and red, so we want close to an even split of Forests and Mountains. However, most of the cheap plays are green, and this deck really wants to be able to cast Elvish Visionary early in order to come out as smoothly as possible. Counting the Llanowar Wastes as a source of green mana, and the Evolving Wilds as both red and green, seven Forests and seven Mountains makes nine total green and eight total red. (I chose not to count Meteorite, because this deck really needs both red and green mana before turn five). If I decided to play an eighteenth land, I'd make it another Forest.

Hopefully, that example gave a basic sense of what you should be thinking about when building a mana base.

If your deck has a good mana base and a balanced mana curve, you've managed to avoid one of Magic's most dangerous pitfalls. If you can make your mana serve you well, instead of feeling helpless against awkward mana draws, you're well on your way to success.