Duskmourn: House of Horror | Episode 5: Don't Give In

To Tyvar's transmutation magic, the substance of the floor and walls was identical to the flesh of the monster that had attacked them. It was unnerving to think they were walking through the body of something alive and hostile. Still, as Tyvar wrapped them in the body of the House, they were able to cross rooms and navigate halls without being attacked. He dropped the camouflage whenever either of them started to feel unfamiliar emotions tugging at the back of their minds, keeping them free from the transformation.

Zimone had to admire the skill with which he cloaked and uncloaked them, walking the thin line between safety and loss of self. During a pause, she asked how he knew what to do, and watched as his expression turned pained.

"During the assault on New Phyrexia, I watched many of my allies lose themselves forever," he said, voice hollow. "Upon my return home, to my fair Kaldheim, I saw that same fate befall too many. I saw the World Tree burn. Koma, who I had revered, whose favor I had sought, fell to that cruel transformation. I felt it spread, across two worlds, and I know what the process feels like to the magic of my own changes. I simply wait to feel like the world is ending, and when it does, I let the magic go."

"I'm sorry," said Zimone. "I didn't mean to—"

"But, we should be moving along," he said, jovial once more. He put one hand against the wall and the other on her shoulder, and the flesh of the House flowed over them, and sorrow and grief and loss were suddenly far away, hidden behind a veil of nightmares.

On they moved, through shifting rooms and portrait galleries, past another library, this one with empty shelves and scraps of paper littering the floor like blood-stained confetti. Zimone still looked at it longingly, like she wanted to stop and reassemble the slaughtered stories of this dead place from the bodies they had left behind.

Tyvar flickered their concealment off and then on again, buying them time, and they moved on, into an impossible room:

It was large and cozy, outfitted with several small couches and large, overstuffed chairs, the styles of furnishing apparently chosen to blur the lines between the two. Shelves lined the walls, filled with a mixture of books and knickknacks, and pleasant pictures hung on the cream-colored walls. There were no strange smells or unlikely shadows, no bloodstains or nightmares. It was just … pleasant, the sort of place either of them would have been perfectly willing to doze an afternoon away.

Sunlight streamed through the two closed windows, bathing the teenage girl who sat on one of the larger couches, a diary open on her knee. She wrote a line, then paused, sticking the end of her pen in her mouth as she looked thoughtfully out the window at the quiet-looking street below. She had a tumbler of amber liquid filled with ice chips, tea maybe, resting on a low nearby table, and looked as peaceful as she was out of place. This room didn't belong here. It was antithetical to the House around it, and it shouldn't have existed.

Zimone gasped, grabbing Tyvar's arm in her surprise. He turned to look at her, frowning slightly.

"I know her," whispered Zimone. "She was in the picture that I found in the first parlor, all the way back when we first came inside! But that picture was very old … she's younger than I am. How …" She fumbled for her detector, raising and sweeping it in front of her like she was scanning the area. "There's no active time magic here. How can she be younger than I am?"

"Perhaps she's a ghost?" suggested Tyvar. "A spirit of some sort? She doesn't seem to be aware of our presence, and even wrapped in the body of this house, I'm difficult to overlook."

Zimone looked at him unbelievingly. "Are you bragging about how hot you are? Like, right now?"

"I am simply stating facts—and look. She's leaving."

The girl, who still hadn't noticed them, rose, taking drink and diary with her as she left the room. The transformation was terrible and swift. Clouds immediately choked the sky outside, swallowing the sunlight; the wallpaper began to peel; and as the curtains slithered shut across the now-dark windows, blood began to bubble from the floor, marking her footprints.

"That doesn't seem good," said Tyvar.

"No, it's not," said Zimone. "Come on." She took off after the girl, and this time it was Tyvar who was forced to follow.

They caught up with her in the next room, a small conservatory that was coming to life around her, dead plants turning green and standing up straight, ambitious vines releasing their grasp on walls and furnishings as they retreated into their pots. Zimone watched all of this with an eagle eye.

"I think I understand," she said, slowly. "Whatever she is, she's repelling the House. It can't touch her. I just don't know why—and I think that's why she can't see us. If the House can't attack her in this room, we should be safe here. Let the transmutation go."

Tyvar nodded and released the spell. The two returned to ordinary flesh, and Zimone cleared her throat. "Hello?" she called.

The girl turned, seeming to see them for the first time. Confronted with a strange woman wearing unfamiliar clothing and carrying a boxy scanner, and a shirtless, barefoot elf, she did the only reasonable thing: she dropped her drink and screamed.

"Oh, no!" yelped Zimone. "We're not here to hurt you! We just wanted to talk to you."

"What are you doing in my house?" demanded the girl.

"Wandering lost, trying to evade an almost certain death, and searching for our friends, who were separated from us by a maliciously appearing wall," said Tyvar.

The girl just looked more confused.

"I'm sorry," said Zimone. "We were following an unexplained phenomenon, and we wound up here. I'm Zimone. You are …?"

"Marina," said the girl. "Marina Vendrell. Unless you're here to kill me, and then I'm about to run outside to scream for the watch."

"A lovely name," said Tyvar. "Both of them. I am Tyvar Kell, prince of Skemfar. We aren't here to kill you. May we speak?"

"I … suppose," said Marina. "How did you get in here?"

"Through the door," said Zimone. "We need to know what happened to the House."

"What do you mean, what happened to the house?" Marina frowned, apparently confused. "It's the house, same as it's always been. Are you all right?"

"The House has always had monsters popping out of its walls and trying to eat people?" asked Zimone, horrified.

Marina stared at her. "What? No!"

"I found a book in the library about the history of this place, and it didn't mention the monsters, either," said Zimone. "So, something clearly happened."

"Oh, you mean An Architectural Accounting? That was started by the last person to live here. Bit of a weirdo, by all accounts—she felt a house should be treated with the respect you would show a living thing. She lived here for many years. Died here, too. When we bought the place, the realtor asked us to update it—it was one of the conditions of sale, that we keep the book current with our occupancy. Mom and Dad thought it was silly, but I thought it was sort of sweet. Everything deserves to be respected for its place in the world."

"That's the book," said Zimone.

"Was that the one with the academically unpleasant magic annotated in the margins?" asked Tyvar.

Marina flushed red. "I was just taking notes," she said.

Zimone frowned. "That was you? Marina, that kind of magic is—well, it's dangerous. People could be seriously hurt, or worse, if you used anything like that. Did you use something like that? Is that what happened to the House?"

Marina responded like a much younger child being told that she'd been naughty: she clamped her hands over her ears and screwed her eyes tightly shut, chanting, "You're not real, you're not here, you're not real, you're not here."

While the square of floor directly under her feet remained unchanged, the rest of the room began to warp and twist, the walls opening into holes from which crawled pustulant nightmare beasts, their long, multijointed limbs reaching for Tyvar and Zimone. Zimone took a sharp step toward Marina, reaching for the girl, only to be stopped by Tyvar grabbing hold of the back of her shirt. He ran, pulling her with him.

Deeper into the House they went, the beasts in pursuit, until they managed to whip around a corner and flatten themselves up against a wall, letting the House-flesh creep over them as Tyvar's magic took hold again. Panting, they pushed free and peeked back into the hall, watching as the house-spawn thundered furiously past.

"The House protects her," said Tyvar.

"Looks like it," said Zimone. "She has something to do with whatever happened here, I know she does. And we have the proof."

Tyvar frowned. "Proof?"

Zimone held up the small, tattered book she had grabbed before being pulled out of the conservatory.

"I got her diary," she said.

"Normally, I would view this as a massive invasion of privacy," said Zimone. It had taken them three rooms to find an unbroken table where they could settle to review her find. "I looked at Rootha's diary once, and she went on this whole little monologue about how easily people burn. I'm not even sure she was trying to scare me by the end. She was mostly just reassuring herself, and fire keeps her calm. Anyway, diaries are supposed to be top secret, don't look, not ever, but I think our circumstances are a little unique."

"You seem to be talking yourself into it," said Tyvar.

"Do you have diaries on Kaldheim?"

"Among my people, if a thing is not meant to be repeated, it should not be written down," he said. "Stories and sagas are for sharing, and secrets are for swallowing, to keep them safe from other eyes."

"Oh. Well, it's a good thing for us that she keeps a diary, because we need to know," said Zimone, and opened the little book to the beginning.

Marina's handwriting was crisp and reasonably clear. Zimone began to read.

I don't want to move, but what I want doesn't matter, because we're moving. It's "better for Dad's work," and I'll be going to "a great new school" where they're sure I'll make "so many wonderful new friends."

Yeah. Because sixteen years in our old neighborhood with only the other weirdos to show for it absolutely has me primed to be the social butterfly of a new scholastic environment. I'm more of a social moth. Stick to the shadows, stay out of the way, and hope I don't get swatted before I can find a lantern to immolate myself on. Not like they'd notice, which, as much as they're trying to pretend I'm not here …

"It goes on like this for a few pages," said Zimone, flipping forward. "I think Marina was really lonely, and sort of scared by the move, so she pretended she didn't care. But wait, here …"

She began to read again.

The presence I felt in the basement when we first moved in, I felt it again, so I went down to see what I could find. This time, it talked to me! His name is Valgavoth—Val—and he was summoned here and bound by one of the owners before us. They thought he would be like the little service spirits people call to do simple tasks, and when they realized how big he was, how powerful, they panicked and ran, but they didn't release him. He's been here this whole time, alone. He says he can give me a list of books that might help me figure out how to free him …

"And I think this is where she started doing the academically questionable research," said Zimone. "There's some really dense stuff here, about demonology and necromancy and spirit-binding, and it all adds up to bad news. But this Valgavoth was captive, and for the House to be this active, he must still be here."

"Even now?" asked Tyvar, seemingly enthralled. "Read on, skald, and tell me the tale."

"You're very weird," said Zimone.

I read the books, and I think I could let him go, but I … I don't really want to anymore. School's still awful, and maybe it's mean of me, but Val is the only real friend I've made since we moved here. I don't want to lose him. Also, he's been locked up for a long, long time, and he's pretty mad about it, even though he tries to pretend he's not when we're talking. I think if I let him out, he might hurt a lot of people before he leaves. I don't want to hurt a lot of people.

"So, Marina was essentially a good person at one point, even if she was making poor academic decisions," said Zimone.

"It seems."

"Something must have changed," said Zimone. She rubbed the back of her head. "My thoughts are starting to itch. Let's be ourselves for a few seconds?"

Tyvar nodded, dropping the transmutation. The crushing weight of the House's regard rushed back in, and after a moment, Zimone said:

"Okay, put it back. I don't want to keep reading while the House can see us."

Today was the worst day yet. Some of the girls in my necrobiology class decided to corner me after class and they—

What they—called me—pushed me—the wall.

"A whole bunch of this has been scribbled out," said Zimone. "But what's left looks pretty bad. There're tear stains on the paper. I think they hurt her bad enough to make her cry."

Val says he can make them pay for what they did. He can make them suffer. I don't care anymore. I can't live like this.

I'll invite them over tomorrow after school.

Zimone flipped to the next entry, barely breathing:

What have I done?

He took them. Hands reached out of the walls and grabbed them, and they were screaming and screaming and changing, like he was moving underneath their skin, and then they stopped screaming and he pulled them into the walls and they were gone. Nothing left at all.

I did this. He's trapped: no matter how angry he is or how much he wants to hurt people, he couldn't have done it without me. I did this to them. I let this happen.

I can't sleep. The house keeps creaking, and the walls are pulsing, like they're trying to breathe. I keep thinking I can hear them moving in there, trapped inside the house, trying to get away.

I did this.

Zimone looked up. "Oh, no."

She turned to the next entry:

The houses to either side are gone, and our house is bigger now. I think Val is the house, somehow, after all this time, and he's hungry and he's angry and I gave him the power to start eating the world around him. I can't let this go on. I have to talk to him. I have to find a way to save myself, to save my parents. Maybe I can't save the world, but I don't have to be entirely a monster, do I?

It's not too late.

Zimone closed the diary, staring at the wall as she set it to the side. "Those rituals she was researching … with the power from four people's lives, Valgavoth would have been able to expand his reach exponentially. Trap more people inside himself, and then do it again, and again, and again. Until there was nothing left outside."

"What do you mean?"

"I don't think there's a plane left outside the House." Zimone turned to look at Tyvar, face strange under her mask of horror-house, eyes wide and terrified. "I think at this point, mathematically speaking, Valgavoth is all."

The outdoor "room" where they had encountered the dancing wickerfolk was connected to more of the same, "rooms" containing forests and thorn breaks and desolate hillsides. Nashi led them deeper and deeper, through environments that should never have been contained in this manner. The Wanderer thought she heard a river running in the distance, water breaking over stones, and as impossible as the sound was, she wanted to follow it to its source. She wanted to know.

Every time it started to feel like they had managed to leave the House, there would be a glimpse of wall or a glint of light off a half-hidden window; however natural these environments felt, they were all fully contained. Niko shuddered at the sight of an earthen mound studded with bones and surrounded by trees, so like the cairns of Kaldheim, so unlike the tombs of Theros. The differences didn't matter. They looked at the similarities, and they knew a graveyard when they saw one.

The group walked on, Nashi still leading the way, although Winter nodded encouragingly when anyone looked to him, indicating that they were on the right track. Forest bled into thicket into briar, until they emerged into a broad meadow too impossibly large to be contained. Huts were scattered across the rolling hills, some with smoke rising from their chimneys, making gray streaks in the pale air. Somewhere during their journey, the lights had come back on, slowly at first, getting brighter by degrees, until they could see every inch of the terrible landscape around them.

Even in the "outside," the House continued to haunt them. Screaming faces were etched in the bark of looming trees—and after the wickerfolk, it was impossible to say whether the trees screamed because they had grown that way, or because they had once been survivors and were still intelligent and aware of their frozen fates. The brush that rose from the hillside in stunted clusters was suspiciously bony, giving the impression that it might close on a foot or snag a hem at any moment.

This was not a good place, no matter how fresh the air seemed, or how merrily the rivers ran.

Winter made a small, unhappy sound. The Wanderer and Niko looked to him, and he shook his head. "This is the Valley of Serenity," he said. "The Cult of Valgavoth lives here. We should go back."

"My mother has been calling me from this direction," said Nashi. "I know we're in the right place."

"But—"

"You don't have to come. I didn't ask you to follow me here."

"We're going with you, whatever that means," said the Wanderer. She shot Winter a challenging look.

Winter sighed. "Don't say I didn't warn you," he said, and the trio walked on.

The Wanderer's glimmer still drifted around her shoulders, circling her as she walked. Niko pulled a shard out of the air, spinning it between their fingers and looking thoughtfully at Winter.

"Who's this cult you're talking about?" they asked.

"The Cult of Valgavoth," said Winter. "They claim Duskmourn was created by an entity summoned by their ancestors, one who took root in this House and grew to swallow everything. The demon called Valgavoth is as trapped here as the rest of us, but he doesn't mind so much anymore, since he eats well. This is a perfect feeding ground for something like him, fertile and flourishing. The cult hunts survivors, both the ones who were born here and the people like me and my friends—or you. They catch us when they can, and drag us away to either be converted or given to Valgavoth. Either way, the ones they capture never come back."

"They sound like charming people."

"They're not."

"I was being sarcastic."

"I know."

"Then why—" Niko caught themself, shaking their head. "Never mind. This cult is bad news, then?"

"The very worst," said Winter direly.

Niko looked at him. "After the wickerfolk, the razorkin, and the glitch ghosts, this is what you want to call the very worst?"

"You'll see," said Winter. He sighed. "I was hoping it would take us longer to encounter them."

"So, you knew we'd encounter them."

"They're inevitable in Duskmourn. They, like their Devouring Father, are everywhere."

Niko frowned and followed Nashi and the Wanderer through a stone tunnel shaped like a doorway, into the next room.

It looked like a natural cavern worn out of rock by centuries of erosion, the walls rough and uneven, the ceiling bristling with stalactites. Some matching stalagmites grew up from the floor, but most of those showed the signs of intentional reshaping, their tops chipped off and smoothed out to make flat surfaces supporting sacramental lanterns, bowls, and even a large stone slab altar made by setting a sheet of hand-chipped quartz atop four leveled stalagmites.

All those things were set dressings, immutable facts of the environment, and nowhere near so disturbing as what the room contained. Half a dozen humanoid figures in long robes shaped like moth's wings, clean and well mended but tattered at the hems. It took Niko a moment to realize why the condition of their clothing was so ominous.

There were no patches. No stains. They had the luxury of caring for themselves in a way that Winter never had, and by extension, the rest of the survivors wandering the House would have been denied. In this place, cleanliness was virtually a declaration of power.

Chrysalises hung around the edges of the room, hard, angular things that gave the impression of natural and unnatural geometry at the same time, like they were shaped from platonic solids dredged out of another dimension. They were painted in shades of green and brown, and as Niko watched, one of them twitched, moved by something from inside. It was unsettling. It hurt their eyes to look at for too long.

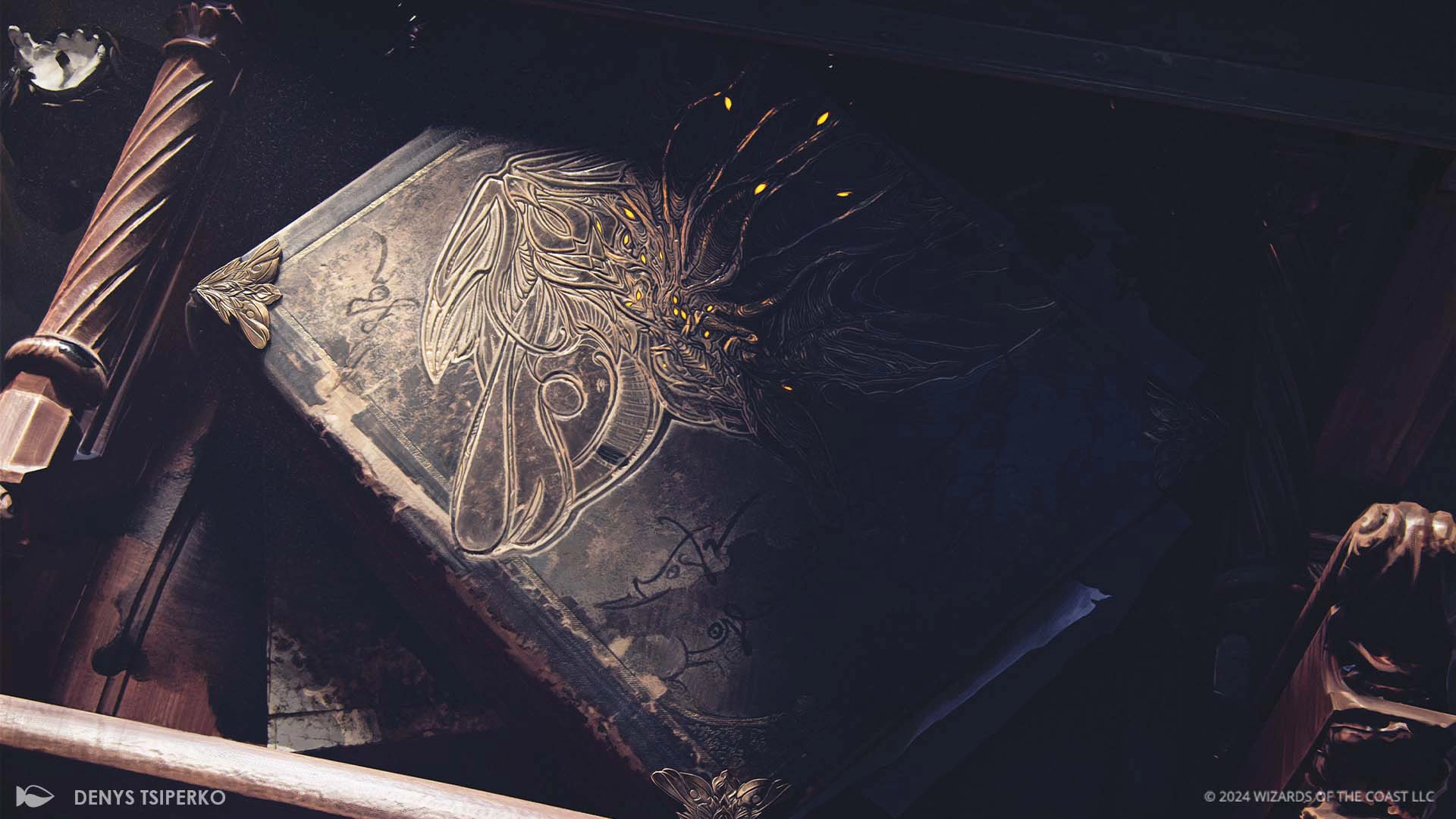

Three people in clothing more like Winter's were bound at the center of the room, struggling weakly against the ropes that held them. One had a vicious-looking gash on her leg, cutting through layers of fabric to the flesh beneath; the other two appeared to be unharmed. One of the robed figures—who held a leather-bound book close to his chest—was preaching to them.

"The Devouring Father has not yet refused your service," he said, voice sonorous and rolling, clearly pitched to beguile. "Be reborn in his name, and you may yet be transformed in glory, cleaned of your fear by the Gift of the Threshold. Wouldn't it be glorious, children, to no longer be afraid? To no longer walk wrapped in the chains of your weakness, unable to stand proud and confident beneath his eaves?"

The injured survivor began to cry, noisily. "Yes," she said, through her tears. "It would be so nice. I've been so scared."

"Hush," hissed one of her companions. "They have our gear, but we can still get out of here. We can survive this."

"We can't! I told you and I told you, but you didn't listen, because you wanted to be brave. Well, being brave isn't the same thing as being unafraid." She looked at the speaker, eyes wide and wet. "I don't want to be afraid anymore."

"Take her," said the speaker.

The other figures—cultists—moved forward, cutting her free. One of them kissed her forehead. Another took her arm. As a group, they pulled her toward the nearest chrysalis, which was split down the middle, and began to ease her inside.

Niko couldn't watch any longer. They jumped onto the nearest stalagmite, a shard appearing in either hand. "Hey!" they yelled. "Leave her alone!"

Slow and deliberate, the speaker turned to look at them, and then at their companions. "Amazing," he said. "You actually did it."

The Wanderer began to step forward, only to feel a strange, placid feeling seep over her. It wasn't enough to drop her—she had more willpower than that—but it made the hands that suddenly grabbed her arms from either side feel as though they were made from iron. Nashi moved to her side, and was restrained in a similar fashion, as were the other nezumi, leaving only Niko and Winter free.

Niko dropped down from the stalagmite and moved to flank Winter, clearly intending to help the man avoid capture. Winter only bowed his head, saying nothing, as the cultists rose up and grabbed Niko in turn.

The speaker moved toward the pair as Niko struggled, trying to break free. He smiled and placed an approving hand on Winter's shoulder. "You shall be most favored," he said.

"At this point, I better be," said Winter, and stepped backward, pulling a loose stone from the wall. A slab of solid granite crashed down between him and the others, sealing them in the room with the cultists.

It was an unfair fight to begin with. One of the greatest swordswomen in the Multiverse, a javelin thrower who couldn't miss, and Nashi, who had learned survival on the streets of Kamigawa, running with people who didn't have his safe home to retreat to, against seven cultists. There was no way for them to lose.

But then, their leader raised his book and blew across the pages, and a thick layer of dust rolled off the paper, gleaming silver in the light as it coated everything around it. Their limbs became heavy, and their movements became slow, and then they blacked out briefly, falling into a nothingness that was purely outside of and distinct from sleep.

The Wanderer was the first to wake. Being jerked back and forth across the Multiverse by her own spark for years had left her better equipped than most to recover from sudden shocks to the system, and she was able to shake off the lingering effects of the sedative dust to find herself held up by loops of some white, cottony material, pinning her tightly to a post. They were in a different cavern now, this one larger and darker, with jagged outcroppings of rock on the wall. She could see her companions, tied to stone posts of their own around the edges of the room.

One wall was taken up by a vast, pulsing cocoon that throbbed like the beating of a heart, the whisper-soft sound of its contractions and expansions echoing through the chamber.

At the center of the room was another altar, and on the altar, a square device like the one Winter carried, like the ones they'd seen abandoned around the House. The top was open, and Tamiyo's scroll echo floated there, flickering in and out of focus, like it hurt her to be manifest. Her shoulders were slumped, and her head was bowed, and she spoke in a voice too soft for the Wanderer to hear to the man in front of her, who was writing down her every word.

"Such delicious stories," said a voice to her left. She whipped her head around, as far as she could, and saw the man who'd been leading the ritual in the first cavern standing beside her, book still in his hands. "She was a glorious discovery, a jewel beyond all price, and we are beyond honored to have her."

"She's not a thing to be taken," spat the Wanderer.

"And yet we took her," said the man, almost jovially. "The Devouring Father has no interest in leaving Duskmourn. This has been a glorious cocoon to feed and nurture him, and he has grown strong. But the space outside the walls has changed recently, and now he can spread his blessings even further, to more and more new worlds. He no longer needs to strain with all his might to open a door. All he needs is to know that they exist."

The Wanderer tried to struggle against her bonds. She could hear Nashi and Niko beginning to stir. "You're stealing her stories. You're giving them to a monster."

"If you wish to remain heretics, I cannot save you, but we would be gloriously glad if you would join us," said the man, sounding almost sorry. "The offer is made. You need only accept."

The Wanderer scowled, shaking her head. The man sighed.

"A pity and a waste, but you have time to change your answer."

Book under his arm, he walked away from her, toward the altar where the memory of Tamiyo helplessly recounted her life's work for a cruel audience.

The sounds of Ravnica were like an assault after the eerie quiet of Duskmourn. Kaito spun around, wary of the possibility of attack. He was in the alley where he had first met Zimone, where this had all begun—had he been aiming for Ravnica? Had he been aiming for anything? He'd been desperate to escape before it was too late …

Something bit into his clenched palm. He forced it open. A piece of bloodstained wood rested in his hand, a parting gift from Duskmourn. Kaito scowled at it, then cast his awareness out across the Blind Eternities, searching for the tainted foundation of the House. Grasping hold, he attempted to throw himself across the void, out into the infinite—

And nothing happened. Panic momentarily gripped him, hand snapping shut on the splinter as fear bubbled up from the pit of his stomach. Had the time come for his spark to blow out as well, leaving him as dependent on the Omenpaths as so many of the others? Was he trapped? Was Kamigawa without a defender who could react with any proper speed?

Panic put that same speed into his heels as he hurried down the alley toward the spot where Niv-Mizzet and the others had set up camp. Aminatou and Etrata saw him and waved for him to stop, but he continued onward, heading for the quarantine zone.

He was almost there when Niv-Mizzet closed a great talon on his shoulder, pulling him to a halt.

"Kaito, what happened?" he asked, almost gently.

Kaito stopped. "We were separated, and then Jace … Jace was there."

"Beleren?" demanded Niv-Mizzet.

"He left me." Kaito looked at Niv-Mizzet, offended. "He said he was sorry, and he left me."

Aminatou and Etrata had reached them by that point, Yoshimaru on Aminatou's heels. She reached toward Kaito, then appeared to think better of it and pulled her hand back. "What you fear hasn't come to pass," she said. "You're still lit, and not yet blown to embers. The trouble isn't in you. It's in the House."

"The House?" asked Kaito.

"It knows you now. It knows you're more trouble than you're worth. It doesn't want you inside its walls. Your friend's fate depends on the people who are already with him. If you chose wisely, he'll be free."

Proft walked up to the small group, moving with less urgency than the others. He looked to Kaito's hand, which still clutched the broken-off piece of Duskmourn.

"If you would come with me, I think I have an idea that might help us," he said, and motioned Kaito forward.

Lacking any better ideas, Kaito followed him back over to the workstations on the other side of the courtyard. Time was passing. And it wasn't on their side.