Gimme a Hand

Welcome to Opening Hand Week! This week we'll be exploring the first thing you see each game, your opening hand of seven cards. When I first started to think about what to write for this topic, I realized that I didn't have one big thing but rather a number of small things. As luck would have it—seven small things. Perhaps you can see where this is going. This week I'm going to talk about seven different topics, all tied to the opening hand. It is a sort of random gathering of material drawn from my "deck" of inspiration. Let's hope I don't have to mulligan. (Yeah, I'll be covering mulligans before the column is over.)

- Draw #1

An opening hand in a game of Magic is seven cards. Have you ever wondered why? While thinking of topics for this column this came up, and I realized that I had no idea. My best guess was that seven is one of the more common numbers for card games where you draw cards and perhaps it won out because it was what Richard Garfield thought people would assume to draw.

Quick aside, have you ever noticed that the vast majority of card games have initial draws that are odd numbers? Have you ever wondered why? It's the same reason that comedic beats almost always have an odd number while premade lists more often than not have an even one. The answer is that even numbers feel more structured and odd numbers feel more natural. Why? It's just the way the human brain is wired. When dealing with things that have tempo or rhythm, humans are more comfortable with odd numbers. When dealing with things that are orderly, humans prefer even numbers. Humans like having their open draws feel more natural and thus are drawn towards odd numbers.

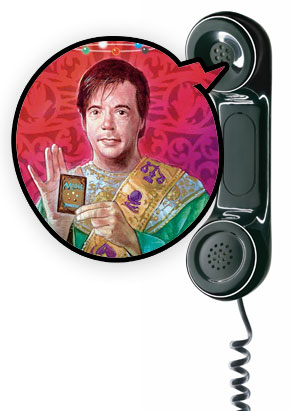

Anyway, I had no idea why the opening hand size was seven so I did something that I have the great pleasure of being able to do: I called Richard Garfield.

Another aside (what can I say, I do love asides), my job is my dream job so it's got so many wonderful perks. One of them has been to have the chance to get to work with and know Richard. For starters, he is the best game designer I've ever met. He has a historical knowledge of games that I've seen rivaled by only a few people (Richard and Skaff Elias, by the way, have actually taught a college class on the history of games) and a wonderful intuitive sense of how game design works. Second, Richard is awesome to hang out with. He's very funny and quite entertaining. Third, Richard has a joy about him that is contagious. He really loves what he does and it just makes spending time with him extra enjoyable.

So I called Richard up on the phone and had the following conversation: (as always there is some dramatic license)

Me: Hello Richard, It's Mark.

Richard: Hi Mark.

Me: So, I'm writing this column on the opening hand and I was wondering if you remembered why you chose a seven-card hand?

Richard: Hmm.

(Pause as Richard thinks.)

Richard: I'm not sure.

Me: Here was my best guess. The most common opening hand sizes I believe are five, seven and thirteen.

Richard: Are you talking poker?

Me: Not just poker. Card games in general. Uno and Go Fish are seven. Dominion and multiplayer Cribbage is five, most trick taking games are thirteen.

Richard: I don't consciously remember why I chose seven. It felt right. I assume I was subconsciously influenced by games I liked.

Me: What about Cosmic Encounter?

Quick aside, while Magic has many influences, Richard has gone on record as saying the game that had the biggest influence on Magic was the game Cosmic Encounter which from a game design history standpoint is really the game that defined the genre of "rule-breaking" games that allowed players to subvert the game's rules.

Richard: Let me look.

(I wait, as Richard looks it up on his iPhone.)

Richard: Yeah, draw seven.

Me: It's probably safe to say that that's what influenced you the most.

Richard: Yeah, that's safe to say.

Me: Because once I put it into my column, that's going to become the definitive answer.

Richard: That seems right. It's the best answer I can come up with.

Me: Official answer: Seven just felt right. You were probably subconsciously influenced by Cosmic Encounter. Got it.

And that is about as a definitive an answer as I can give. By the way, if you've never played Cosmic Encounter, I heartily suggest giving it a try.

- Draw #2

I have designed some broken mechanics in my day. The "free" mechanic from Urza's Saga was mine. Affinity, (based on an earlier mechanic created during Tempest design by Mike Elliott) from Mirrodin was mine. Artifact lands, also from Mirrodin, was mine. Storm was ... no wait, that's all Brian Tinsman's fault. But not one of these holds a candle to the most broken mechanic I've ever designed. Luckily, this one never made it to print.

It happened during Tempest design, the first design I was ever on. (Also the first design I lead—designers' first outing on a design team are no longer lead design of large sets.) The design team was myself, Richard Garfield, Mike Elliott and Charlie Catino. It was a pretty potent design team and I was trying to really innovate and impress the rest of the team.

My idea was for a series of cards that if you put them in your deck, you could just choose to have them in your opening hand. The cost was that you'd have to draw one less card at the start of the game. Also, the cards were a little weaker than a normal card. For example, I had a cycle of lands that tapped for C (Ramp;D slang for a specific color) but came into play tapped. I think I wandered down this design path because cards that let you break rules you couldn't break before intrigued me. (Frequent readers will know that this is a bad reason to do something—break rules because they creatively solve your unsolvable problem not just because you can.)

It turns out I broke a rule that just shouldn't ever be broken. These cards were so insanely overpowered (or in Ramp;D slang "bah-roken") that I figured it out without even needing a playtest. Why bother ever playing with pesky lands when you could just have what you need in your opening hand? Every draw will be a playable card. No land drop problems, no variance between games, no suspense—you know, just chuck everything that makes Magic actually fun. I had somehow managed to break one of the things that made trading card games work.

It's not often I kill a mechanic in design for being too powerful, but these cards definitely got that honor.

- Draw #3

Trivia Question: How many Magic cards have the words "opening hand" in their rules text?

When you have your answer, click here.

The answer is ten, only nine of which, by the way, are Leylines:

What's the tenth card?

But wait, isn't there another card that has an ability it can use in your opening hand? Why yes, there is—Serum Powder from Darksteel.

Serum Powder specifically talks about mulliganing (the only card currently in Magic that does) so the template just asks for it to be in your hand as no other time but your opening hand would matter, so it didn't need to be spelled out.

If I asked this trivia question a year from now, what would the answer be?

Fifteen.

- Draw #4

Since I brought up Serum Powder, perhaps this would be a good time for an origin story. How exactly did Serum Powder get designed?

The answer is that Ramp;D didn't design it. You did. Okay, technically that "you" was a man named Gerard Pfiefer who submitted the card for the very first You Make the Card promotion we ran back in 2002 (Forgotten Ancient was the card you all ended up making.) Here's what Gerard submitted: (remember that this was designed to go on a green creature)

Mulligan Man

If you draw CARDNAME in your initial hand, you may reveal it to all players. If you do, shuffle your hand into your library and draw a new hand of seven cards.

The idea didn't work so well on a green creature (we didn't even let the audience vote on it) but Ramp;D really liked the concept.

Remember that at this time, my team and I (myself, Mike Elliott, Brian Tinsman and Tyler Bielman) were working on the design for Mirrodin. One of the things we realized when setting out to do an artifact set was that there were certain qualities about artifacts that had to get represented in the block. One key thing to me was that artifacts had this quality of doing things that have never been done before. For a while, Ramp;D used a term "marquee card" which meant it was a splashy card that drew a lot of attention to itself and did something that had never been done before. I coined the term about Jester's Cap in Ice Age and convinced the rest of Ramp;D that each large Magic set had to have a marquee card in it.

The marquee card in Mirage was Grinning Totem. You could steal and play cards out of your opponent's deck. The marquee card for Tempest was supposed to be Volrath's Helm, which, at the time, was what you now know as Mindslaver. The point here is that when we were looking for cards that just broke away into truly virgin territory, we tended to use artifacts. There is something flavorful about a powerful, mystical relic that granted you some power you've never even seen before.

As Mirrodin was an artifact block, I felt like this quality just had to be higher than normal. That was, for example, one of the reasons I pulled Mindslaver out of the mothballs and tried to finally get it printed. I needed more. Platinum Angel came out of this desire, although, the card wasn't designed by me (I'd credit the designer if I knew who it was). During this same period, Gerard Pfiefer submitted this mechanic.

We changed it from a creature to a noncreature artifact because the ability seemed like it wanted to go on a trinket—some small, magical item you'd keep in your pocket. The artifact itself had to do something simple so that any deck that wanted to throw it in for its mulligan power could make use of it if they didn't mulligan it. In the end, a mana-producer seemed the cleanest answer, so we made it tap for  . The original design name was Mulligan Mox even though it didn't cost

. The original design name was Mulligan Mox even though it didn't cost  (I think the design version costs

(I think the design version costs  ). Mulligan Mox was put into Mirrodin but it kept losing out to other cards. The feeling was that it was an "out of the box" card and Mirrodin had enough.

). Mulligan Mox was put into Mirrodin but it kept losing out to other cards. The feeling was that it was an "out of the box" card and Mirrodin had enough.

As I always do when a card I like gets knocked out of a design, I save it for the next design team I'm on. That was Darksteel. (I was on all three Mirrodin block design teams.) I pitched the card and Bill (as in Bill Rose, Darksteel lead designer) liked it and the card went in the file never looking back.

- Draw #5

I often talk in this column about the differences between design and development. Most of the time I talk about bigger issues, but today I thought I'd talk about a very tiny difference, one that actually deals with opening hands. Here it is: in design playtests we usually don't mulligan while in development playtests we usually do. What do I mean we don't mulligan in design? I mean that if a player has a bad hand, they just redraw a hand of seven cards. In a development playtest, we'll make use of mulligans meaning that any player who needs to draw a new hand draws one card less.

Why is this? It has to do with the nature of design and development playtests. Design playtests are very raw. That is, we are playing to get a sense of the cards and determine whether or not they have potential. Are the cards/mechanics/themes fun? Do they play well? Do they create good moments? Do they have interesting elements to hang other designs on? (One day I'll get to my theory of "hooking"—how cards need to interconnect mechanically to make a set design work holistically.)

Design is very much about playing with various pieces, some of which will advance and some of which will not. Design playtests aren't very balanced. That is, time isn't spent making sure everything is of equal value. For example, design doesn't spend a lot of time on color balance or mana curve. We pay attention to it, but we are not as exacting as development will be.

The reason for this is that design is more art than science. We're trying to get a sense of how the bits and pieces feel. Until we get that figured out, it doesn't matter if everything is balanced. As such, playing games where one side doesn't get to play does very little to help design learn anything.

Development, on the other hand, needs to care about how people play based on all the tiny measurements. They adjust the environment exactly so that they can field test how the players are going to respond to it. Development playtests are much closer to what the players play and as such development wants to put it through realistic playtests. I should stress that development does vary some on how much it cares about mulligans depending on what is being playtested.

Another thing that design occasionally does, that development seldom does, is just start with a certain card or cards in the opening hand. Sometimes when we want to test something, we don't leave it to chance.

- Draw #6

Trivia question: What was the mulligan rule for Magic when it first started?

Click here for the answer.

The answer was there was none. Yes, Magic didn't start with a mulligan rule.

Next trivia question: When the Duelists' Convocation (the DC in DCI and the original name of the governing body for tournament play) published its first set of tournament rules, what was the mulligan rule?

Click here for answer.

The answer was there was still none. You can click here to see the original rules in all their glory.

I couldn't find the document, but sometime during 1994 the Duelists' Convocation put out the very first mulligan rule. You were allowed to shuffle your hand into your library and draw a new hand of seven cards if and only if you had exactly 0, 1 or 7 lands in your hand (which you had to reveal to your opponent).

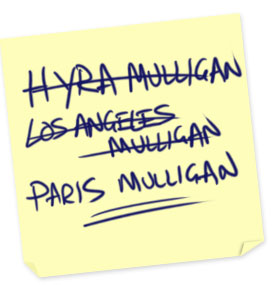

The "Paris" mulligan or what is mostly just known as "the mulligan rule" was introduced at the 1997 Pro Tour–Los Angeles. The second (and first Constructed) Pro Tour to use the rule was Pro Tour–Paris but I guess the "Los Angeles" mulligan just sounded less sexy. Former Pro Player and then Wizards employee Matt Hyra, who came up with it while judging tournaments in the Wizards of the Coast Game Center, created the "Paris" mulligan. (Wizards for a short period of time got into retail gaming.) If you want to learn more about mulligans, feel free to check out my column from Mulligan Week back in 2004.

- Draw #7

For my final story, I'll talk about the design of one other card that cares about being in your opening hand: Gemstone Caverns. Serum Powder was designed by Gerard Pfiefer. How about Gemstone Caverns, who designed it? Pro-player Tsuyoshi Fujita. (Apparently Ramp;D is not capable of designing cards that work in your opening hand, okay, other than leylines ... and future mystery things.) He submitted the card for the 2005 Magic Invitational, the one Antoine Ruel won.

But wait, if he didn't win, how did his card get made? Interesting story. One of the ongoing issues we had with the Magic Invitational was what purpose did it serve. Who exactly was it for? On one hand, it was for the players as an all-star game—as something for them to aspire to play in. On the other hand, the event was made to be a spectator-friendly event. The five formats, the round robin, the who's who list of players. All were chosen to make the event as fun to watch as possible.

In 2005, we thought we would try something to draw in more spectators. There was already a lot of focus on the player-designed cards, as the prize for the winner was that theirs was printed with their picture in the illustration. What if we let the audience choose their favorite card and also printed that one as well? To differentiate it from the winning card, we wouldn't put the winner's picture in the art.

In the end, the idea went over with kind of a thud. At best we could tell it didn't draw an audience and its release was pretty lackluster as we were trying not to upstage the winner. So Gemstone Caverns was the first and last non-Invitational winner's card to be printed. (Okay, technically, cards we have liked have influenced us to make something similar. The most famous example was Chalice of the Void in Mirrodin, which was a tweaked version of a card Gary Wise turned in for one of his player-designed cards.)

The actual design and development was very straightforward. Here was what Tsuyoshi submitted:

Unluckyman's Paradise

Land

If Unluckyman's Paradise is in your opening hand and you're not playing first, you may begin the game with it in play. If you do, Unluckyman's Paradise comes into play with a luck counter on it.

T: Add 1 to your mana pool.

T: Add one mana of any color to your mana pool. Play this ability only if Unluckyman's Paradise has a luck counter on it.

Can you tell what development did? The biggest change was to make the land legendary. It was a little too good when you could play with four. Second, they combined the two abilities into a single ability with a new template. Other than that, what Tsuyoshi turned in pretty much ended up on the final version.

- The Sound Of One Hand Clapping

And with seven tidbits, I'll call the article full. I hope you enjoyed a little peek into my "hand" of cards.

Join me next week when I revisit the past.

Until then, may your opening hands bring you nothing but smiles.