Kids Play, Part 2

There are few things in life that change your world view more than being a parent. Two weeks ago, I started talking about how lessons learned from parenthood have shaped me as a designer. Today is Part 2 of that column. If you haven't read Part 1, I urge you to do so, because I'm writing today's column assuming you have.

- Lesson #6: You're Going to Make Mistakes

When last we left off, Lora and I just learned we were going to have twins. The pregnancy proved a much bigger deal than Rachel's pregnancy and Lora was stuck on bed rest for three months. Finally, Adam and Sarah were born. In lesson #1, I talked about how much work taking care of a baby is. As it turns out, two babies are even more than twice the work of one baby. This is due to two factors. One, you're already tired from the first baby when you get to the second baby, and two, the main interaction between babies is disruptive (one cries and wakes the other one up). The latter changes as they get older, but for the infant years, baby #2 does not do much to help with baby #1.

When the twins were born, my mother again came out to help us. She herself was a twin, so she was quite excited that we had twins. One day, she noticed that something seemed wrong with one of Adam's eyes. We ended up seeing an eye doctor and learned that Adam has a condition known as Microphthalmia, where one eye is smaller than the other. Not only was it smaller but it wasn't a functioning eye, meaning that Adam was blind in his right eye. Now, had this been the first bit of bad medical news we had ever received about a child we might have been devastated, but having come off of a condition with a mortality rate, it didn't seem so bad.

We did some research and learned that one eye can do the vast majority of what two eyes can do. It even has some ability to provide depth of vision. We talked to a lot of adults with blindness in one eye and were comforted by the fact that it didn't create too many limitations. This would have an impact on Adam's life but not too big an impact.

Nonetheless, we decided we wanted to do everything we could to help Adam live as normal a life as possible, so we sought out the best children's eye doctor in Seattle, Dr. Warner. (That's not actually his name but other than family members I'm not naming other people.) Being the best, Dr. Warner was in high demand, and we were unable to get an appointment. That is, until we mentioned Adam's eye condition. It turned out that Dr. Warner's specialty was Microphthalmia. Once he learned Adam had it, we were in.

We saw Dr. Warner for a number of years. One day, he informed us that he believed it was time for Adam to get glasses. We were confused. Tests had shown that Adam's good eye had 20/20 vision. Why did he need glasses? They weren't for vision, Dr. Warner explained, but to protect his good eye. Adam was fine as long as he had vision in one eye but if he ever had an accident and harmed it, then he would be fully blind. To help safeguard against it, he advised that Adam wear glasses without prescription as protection.

We went out that day and purchased a pair of glasses. Adam was four at the time. We did everything we could to build up the glasses. They were going to be cool and exciting. Adam helped pick them out. Then when it came time to finally put them on, Adam refused to wear them.

We decided to give Adam some time and attempted to slowly warm him up to the glasses. Adam would have none of that. See, he didn't need the glasses. He could see fine. We didn't want to make him hate the glasses so we decided to retreat and regroup. We tried again and again but we were never successful.

Flash forward six months, when we had the next visit with Dr. Warner. He asked about the glasses. We told him that we had purchased them and just couldn't get Adam to wear them. That's when kindly old Dr. Warner chewed us out. We were Adam's parents. His safety was our responsibility. It didn't matter if Adam wanted to wear the glasses—he had to. Our job was to make sure that happened.

We didn't argue with Dr. Warner because he was 100% correct. We had failed as parents. It was a very telling moment for me because I had always strived hard not to make any mistakes as a parent. My children's welfare was on the line and I was determined to always do the right thing. It was this moment where I realized I wasn't always going to do the correct thing, but rather than wallow in the mistake, I would use it as an impetus to try harder.

We went home and within two weeks (with some help from my mom), Adam was wearing his glasses. The lesson here is that perfection is a fool's errand. In any endeavor, you're not always going to get everything right. Mistakes are going to happen, but you have to learn to use them as teaching tools to help prevent you from repeating the same mistake in the future. Also, you have to not beat yourself up for mistakes because you have to understand that they're going to happen.

The last paragraph applies almost directly to design. As the lead designer of a set, it's your goal to do everything right and create the perfect set, but you're going to make mistakes and you have to accept that as part of the process. Not only that—not only do you have to accept mistakes as part of the process—but you have to act in a way that can allow mistakes to happen. What do I mean by that? Let me explain.

One of the best ways to avoid mistakes is to never venture into unknown territory. If you stick to things you already understand and have experience with, your chance of making a mistake goes down. The problem is that design, especially trading card game design, has to venture into the unknown. If you are unwilling to accept the possibilities of mistakes, you are unwilling to go places that as a designer you have to go.

Mistakes can be quite shaming (I can still remember how I felt when Dr. Warner yelled at us), but it is through mistakes that we grow as people and designers. As I've talked about in this column before, success makes us feel good, but it is mistakes that educate us.

For example, when I designed Time Spiral block, I was experimenting with pushing the boundaries of block design. I was very excited by designing around such abstract concepts as the past, the present, and the future. While I created work I am still proud of to this day, I also lost sight of the point of what I was doing. I had created something so complex that I was driving hordes of players away from the game.

So in Lorwyn block, I tried to make up for the mistakes of Time Spiral block only to make a completely different set of mistakes. The cards were no longer complex but now the battlefield was. I remember Wizards employees leaving the Prerelease because they were overwhelmed by the Sealed play.

But it was the experiences of designing those two blocks that led me and Matt Place to create New World Order. While there are numerous factors at play, I believe strongly that New World Order was one of the things that has led to Magic's success of late. By lowering the barrier to entry, we've made it much easier to get new players into the game while keeping the complexity for experienced players at higher rarities. New World Order would never have happened had I not pushed the boundaries in Time Spiral and Lorwyn blocks. Without those mistakes, the great breakthrough might never have happened.

In parenthood, as in design, I am going to make mistakes, but I hope that I become better at both from the lessons learned from making them.

- Lesson #7: Make Sure They Have Opportunities

Sarah is the baby of the family (sure, just by one minute, but Adam never lets her forget that fact) but she has the most energy. One of the things we do with the kids is make sure that each one has the opportunity to choose an extracurricular activity he or she wants to participate in. Each has some mandatory activities (we'll get to one of those in a minute) but we wanted the kids to have the ability to pick something that was of their own choosing. Thanks to my position in Magic, Lora has the freedom to be at home with the kids and, bless her heart, has a more complicated driving schedule than any set I've ever designed.

Now, Sarah is the jock of the family. She has boundless energy and picks up physical things very quickly. When she was five, she decided she wanted to take ballet. At the very first class, the teacher asked Lora where Sarah had taken her last class. The teacher was stunned by Lora's response. Sarah had never done ballet before? Apparently, she was a natural.

When the class ended, we asked Sarah if she wanted to take ballet again and she said no. She took acting and then art and then dancing. In each, she was a quick learner and showed promise, but each time, she would opt to do something else. Next came gymnastics. Once again, she quickly rose through the ranks with her natural athletic prowess. The end goal of gymnastics is to start competing on the team. Sarah qualified but wasn't enjoying it. She loved doing the flips and tumbling but she didn't like the harshness that came with competition. Then, during the summer, she went to a camp that did dancing in the morning, cheerleading in the early afternoon, and gymnastics in the late afternoon. At the end of camp, she informed us she wanted to take cheerleading.

Lora and I talked about this request. Sarah showed great promise in so many different areas. If only she chose one, she could focus and become very good at whatever the chosen activity was. That's when Lora spoke up. She said that she thought we were thinking about this wrong. The goal of raising Sarah, or any of our kids, wasn't to create an expert at something. This wasn't some roleplaying game where we were trying to max out a skill or attribute (okay, my metaphor, not hers, but I felt mine would be more applicable to all of you).

We were trying to raise a well-rounded, happy child. Our goal wasn't to solve anything for Sarah but rather to give her opportunity. With time, Sarah was going to figure out who she wanted to be as a person and what things in life she wanted to focus on. Our job, as her parents, is to allow her to experience all the world has to offer, and if she hasn't made up her mind yet what her passion is going to be, that's okay. We have to support her for who she is now and not what she could one day become.

Magic sets are very similar. One day, your set is going to figure out what it is and focus, but early on you have to open up the set to possibilities. Oftentimes, I'll have design team members make suggestions that I personally don't think are going to pan out, but if I think they might show us something new, I'll put them into the file. Sometimes they do work out and other times they get us somewhere we wouldn't have gotten without those ideas as stepping stones.

As I talked about two weeks ago, there are always surprises and you have to be willing to adapt to them as they happen. This lesson is that you have to open yourself up to opportunities to allow those surprises to occur. And don't let your fear of mistakes keep you from that path. (See, all these lessons really do tie together.)

I had no idea what the timeshifted cards were going to do to Time Spiral when I proposed them, but their existence fundamentally reshaped what not only the set was but how the whole block worked. The defining quality of Future Sight, for instance, ended up being the future-shifted cards that only existed because of Time Spiral's timeshifted cards.

As a designer, I've learned to let my sets—as I let my children—explore, so they can figure out who they're going to become.

- Lesson #8: Listen To Them

Above, I talked about how our kids had some mandatory activities. One of those is swimming. The rule in our house is until the day that you can easily get to the side of a pool if you accidentally fall in, you're taking swimming lessons. Both Rachel and Sarah were naturals in the pool and quickly got to the point where swimming lessons were optional. Adam, not so much.

You see, Adam, like many children, has always been afraid of the water. He loves playing in it, but get him to the point where his feet aren't easily touching the bottom and he gets scared. For years we took him to lessons at the local pool. While his sisters kept advancing classes, Adam always remained in the lowest class, afraid to even put his face in the water.

As we had learned from the glasses incident, we weren't going to let Adam walk away from something that would protect him, so the lessons continued. Year after year, nothing seemed to change. Adam went from being the youngest in his swimming class to being the oldest. Frustrated, one day I sat Adam down and we had the following conversation:

Me: Adam, why don't you like swimming?

Adam: I do like swimming.

Me: Why won't you put your face in the water?

Adam: Well, I don't like that.

Me: Why?

Adam: It's scary.

Me: Can't your teachers help you make it not scary?

Adam: No.

Me: Why not?

Adam: Because they don't care.

Me: What do you mean?

Adam: The big guy told them to not worry about me.

Me: Why did he say that?

Adam: I was wasting too much of their time.

Adam wasn't improving because the instructors didn't have the time to give him the attention he needed. He had been written off because they didn't have the resources. The answer was clear. Adam needed a private lesson.

The thing that struck me was not the solution to the problem but the fact that Adam had the facts necessary to reach the conclusion. We had been spinning our wheels for years because I never thought to go to Adam and find out if he knew what was wrong. Being the adult, I just assumed I knew more than he did.

We immediately sought out a good private instructor and Adam has been taking lessons there for almost a year. It's slow going, but Adam is now putting his face in the water and, more importantly, he's excited to go to swimming lessons.

The lesson applies pretty directly to Magic design. One of the things I tell my designers is "listen to your set." When you playtest, certain cards or mechanics or themes will rise to the surface. They will be the cards that playtesters talk about or that keep drawing your attention. The cream will rise to the top, but as the lead designer you have to pay attention. Likewise, some things will not work and you also have to pay attention to that information as well.

During Zendikar, for example, I knew I wanted a land mechanic but I was looking in the wrong place. I was fascinated by the idea of the land drop as a resource, but playtesting kept showing that it was this very aspect that was frustrating people. It forced players to do things they didn't want and it often punished them when they did. The solution to the problem was to go the opposite direction. Instead of forcing them to do what they didn't want to do, how about reward them for what they wanted to do—play land? And that was how landfall got created, by listening to what the set (and the players) wanted.

Sometimes your kids or your set will fight you (see lesson #2) but sometimes they'll help. You'll only be able to know this, though, if you pay close attention to what they have to say.

- Lesson #9: At Some Point You Have to be Willing to Let Go

One of the values I was raised with was the importance of education. College wasn't a question in our household but an absolute certainty. Lora and I have tried to bring these same values to our kids. Their job, we've explained to them, is being a student. They need to learn to the best of their ability. A big part of this is homework.

Throughout elementary school, Rachel always had a single teacher ,so it was very easy to track the homework for each night. We were proactive about making sure that Rachel knew what had to be done each night and ensuring she did it. As such, elementary school went very smoothly.

Last year, Rachel started middle school. (Yes, the same school that I went to speak at Career Day.) Middle school is a lot different from elementary school. For starters, you have a different teacher for each class, meaning that following homework is a much more complex endeavor. At first, Lora and I were planning to use the same approach we had in elementary school, but we quickly realized that it was both impractical and detrimental.

You see, when you take a step back, parenting is all about giving your children all the skills they need to be able to function without you. While you will always be their parent, there's going to come a day where they leave home. When that day happens, you no longer are going to have the ability to safeguard them and you will have to rely on all the work you did during their childhood.

Part of getting to that point is learning as a parent that you are not doing your children a service if you always solve their problems for them. As they get older, you have to find ways to allow them to create their own independence. For Rachel, one of the biggest first steps was getting her to claim ownership of her homework. It was her job to track what needed to be done each night and then make sure it gets done.

We're there as a backup and when she needs help, we step in, but otherwise we're there in a supporting role. This has been a big change for Rachel and there have been a few slip-ups. With time, though, she has risen to the challenge and is now queen of her own homework domain.

Magic design parallels this lesson very closely. Whenever I work on a set, I know it will leave me one day. My goal is to prepare my set so it will have what it needs for its journey to development and beyond.

One of the most common questions I get is what is the difference between design and development. There are many answers, but today I'll explain it this way: Design is about figuring out a set's character. Its mood. Its tone. Design is crafting the broad strokes and giving the set a personality. Development takes what design has crafted and then fine tunes it, makes it practical. Makes it balanced. Makes it work. In order for development to do its job design has to set the agenda for the set and create a vision to aim for. Development figures out how to get the set to where it needs to go but design has to inform development where that is.

Having designed Magic for as long as I have, I've learned that my job as a designer is to do the design and leave the other aspects to the experts in those areas. So what do I have to do with a set before it leaves my purview? I have to instill it with what it wants to be, I have to help it find its heart, and I have to make sure it has the available tools to get the job done. You know, I have to be a parent.

- Lesson #10: Your Children are Going to be Who They are, Not Who You Want Them to Be

One of the great joys of parenthood is seeing glimmers of yourself in your kids. For example, Rachel is a natural performer; she loves getting up in front of a crowd. At her middle school, she is one of the anchors for the morning announcements (school announcements are now done as video broadcasts). Rachel loves directing and is constantly shooting films and editing and scoring them herself. She loves to write and always provides her own scripts.

I watch her practice for an audition and I flash back to all my acting classes. I see her making her films and I remember my days at Boston University's College of Communication. I observe her writing and I... well, that one you might already know. It is a great joy to watch my child reliving so many of my own personal passions.

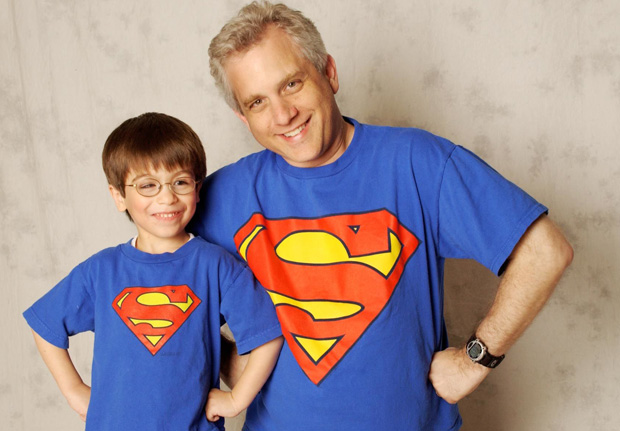

Adam loves games, especially video games. He loves comic books and super heroes. He loves making up stories with his vivid imagination. Forget my childhood. That's all stuff I still do. Buying gifts for Adam is so easy because I just buy him things I would enjoy. Every year I go to San Diego Comic-Con and I come home with a giant bag of presents for Adam for the holidays because our interests overlap so much.

And then we come to Sarah. As I explained above, Sarah is a jock. She's super physical and bounding with energy. She seems to excel at every physical thing she tries. That was not me as a kid (or to be fair, now either). I excelled mentally but physical activity was never a strong suit.

Sarah has a passion for music. I never did. She loves to dance. Not me. Her interests across the board just don't line up with what I knew in my childhood. Note that almost everything I described was true for Lora. She was an athlete and loved gymnastics and tumbling. She adored music and dancing. I can look at Sarah and I see a lot of Lora.

But when I dig deeper, I realized that there's a lot of me there too; it's just buried a little deeper. Sarah is very empathetic and is attracted to helping others. She's very open with her emotions and likes to express how she's feeling. She embraces happiness is a way that warms my heart. (Actually all my kids do this, which is one of my great joys as a parent.)

If I had to predict what my children would be like, I might have guessed Rachel or Adam but I don't think I would have predicted Sarah—but that doesn't make who she's become any less wonderful. I saved this lesson for last because this is probably the biggest lesson I've learned as a parent.

You influence your children, through both nature and nurture, but they are going to be who they're going to be. You're job isn't to change them but to accept them for who they are. More so, your job is to figure out what they are becoming and help that along. Your role as a parent is to support and nurture who they are, not who you want them to be.

This lesson is equally as important in design. A lead designer isn't there to make the set what he or she wants it to be, but to nurture what it is. The role of designer is much that of a parent, using your resources to learn what your set is and how you can help it along that path.

I've watched a lot of sets get designed and I've seen the danger that comes when the lead designer tries to make the set follow his or her agenda. Much like parents forcing their children down paths so they can live vicariously through them, the designers end up with a conflicted set that doesn't ring true.

In reading comments from Part 1, numerous people felt as if I was giving designs sentience. It's hard to explain for those who haven't done it, but a big part of design is letting your own subconscious act as a representative for the set. You create parameters and then you let the set breathe, moving in whatever direction it wants. Yes, down deep you're the one calling the shots but it's a part that you don't have direct control over.

I've often joked that development is a science and design is an art. A lot of this is because design is about getting a feel. The way one creates a vision is to play with the set until some part of it speaks to you. It's the same process I assume a painter has when he or she figures out where the next stroke is going. It's not something you know, it's something you feel.

I'm often asked about how I know that I've finished with a set? You could fiddle endlessly, so how do you realize that you're done? The cynic might say the deadline tells you, but having made a lot of sets, I know that there's just a moment when you know everything's in its place.

How do you get there? By letting the set become the thing it wants to be. A little less technical than my "Nuts & Bolts" columns, I know, but much like being a parent, sometimes you just have feel your way through.

I'm very proud of all my babies, biological and magical. I firmly believe my work in each has helped me better understand the other.

- I Kid, I Kid

I hope you all enjoyed this two-parter. The personal columns always mean a lot to me, so I hope you've enjoyed reading them as much as I've enjoyed writing them. As always (actually even more so than always), I would love to hear your feedback: in an email, in the thread, or on social media (Twitter, Tumblr, and Google+)

Join me next week when things get grave, as it's time for Golgari Week.

Until then, may you be just as proud of your kids, whoever or whatever they are.

This week on the podcast, I examine the cycling mechanic—the non-evergreen mechanic that has shown up in more sets than any other mechanic. How did it come to be and why do we keep using it? Take a listen and find out.

|

Multi

|

- Episode 8: Cycling (14.0 MB)

- Episode 7: Alliances (14.0 MB)

- Episode 6: Gold Cards (16.9 MB)

- Episode 5: Ravnica (12.9 MB)

- Episode 4: Invasion (14.2 MB)

- Episode 3: Planeswalkers (15.0 MB)

- Episode 2: Zendikar (15.3 MB)

- Episode 1: Tempest (13.8 MB)