At the end of each year, we let the website staff and writers have a break and run two weeks of best-of content. Each author gets to choose what they would like to run as their best-of articles. Each year I choose my favorite design-oriented column and my favorite overall article. This year, I'm going to start with my favorite design column. Here were my runners-up:

The article I chose for my favorite design column of the year was "Phooey." Khans of Tarkir

was a block about an alternate timeline, so it seemed only appropriate that design spent many weeks on an alternate card file. This column talks all about why that happened and how it went.

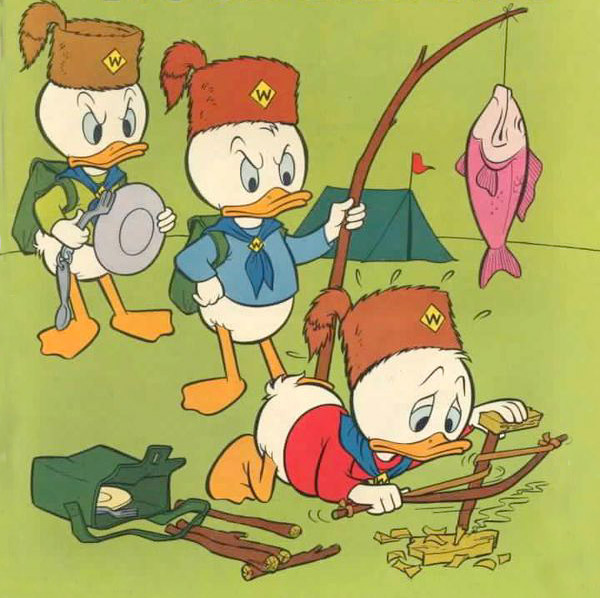

The

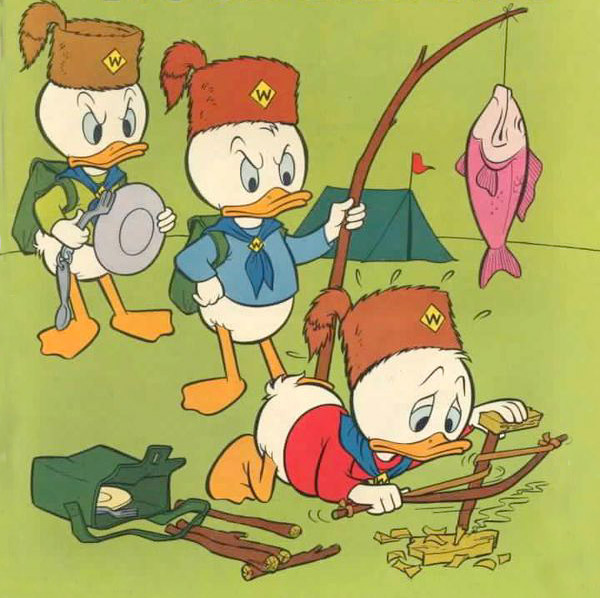

Khans of Tarkir block was codenamed "

Huey", "

Dewey" and "

Louie" after Donald Duck's three nephews. It proved to be a poor choice of codenames as having three rhyming codenames that is each spelled differently was very problematic. (Note that we have both "

Tears" & "

Fears" and "

Lock" & "

Stock" coming up so we haven't quite gotten all the way through this mistake yet.) In addition, while there is an actual order to their names as it's presented in the comics and cartoons, not enough Wizards of the Coast employees knew the order, so people were constantly mixing it up. Once again, the rhyming names didn't help.

It turns out the naming convention had one other by-product. You see, occasionally in the comics an artist would accidentally draw four ducks instead of three, and numerous comics got printed with this mistake. It happened enough times that they actually named the fourth duck, Phooey Duck. So when the codenames became public, I got a lot of jokes from Huey, Dewy & Louie fans about where was the fourth set? Where was "

Phooey"? Little did the people making that joke realize there was a "

Phooey." It was a real set that, for a little while, looked like it was going to get made.

Today's column is all about "

Phooey," the

Khans of Tarkir set that no one outside of Wizards has ever heard about.Well, that is, until today. Sit back, my faithful readers, as I am going to tell you a story of the set of "

Phooey"—what is was, how it got made, and why it never saw print. Sound fun? Then let's get started.

It Began with a Mask

Our story actually starts during the design of

Onslaught(in the summer 0f 2000). I was helping out the design team try to find a major mechanic for the set when I was approached by a member of the rules team. You see, back in the day, there was a number of people who would meet on a regular basis to hammer out different rules issues. One of their jobs was to take troublesome cards from the past and figure out how to make them actually work within the modern rules. Two cards were particularly thorny:

Illusionary Mask | Art by Amy Weber

Illusionary Mask and Camouflage, both from Alpha, had you turn creatures face-down on the battlefield. Neither card really went into great detail about what that meant. They just were unknown. The way it worked at the time was: players would interact with them and then the controller (also usually the owner), who knew what the card was, would explain what would happen but wasn't forced to explain why. The classic example was Terroring a face-down black creature. Terror was another Alpha card that could destroy a non-black, non-artifact creature. When the opponent attempted to Terror the face-down creature, you would just say "Sorry, you can't do that." The owner of the Terror wouldn't know why. That could mean it's black or an artifact or un-targetable for other reasons. They could try Shattering it (an Alpha card that destroys an artifact). You again would say "Sorry." Now they knew it wasn't an artifact.

[card mvid="20">ILLUSIONARY MASK[/card] [card mvid="143">CAMOUFLAGE[/card]

Not only was this process aggravating for the other player, they had the additional problem that they couldn't confirm anything you were saying. It was novel back in the day where cards just did wacky things and you figured it out as you went along, but as we consolidated and streamlined the rules, it stuck out like a sore thumb. The rules team had to figure out a way to make it work within the modern rules. And remember, they couldn't just throw their hands up and say "never mind," the cards in question were already in print.

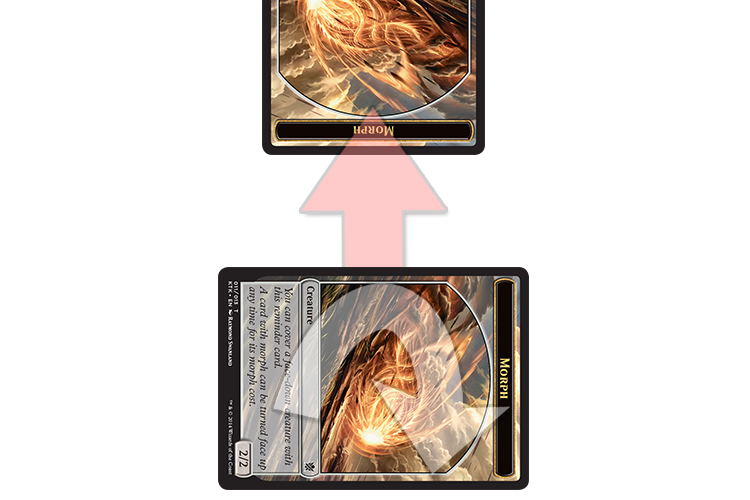

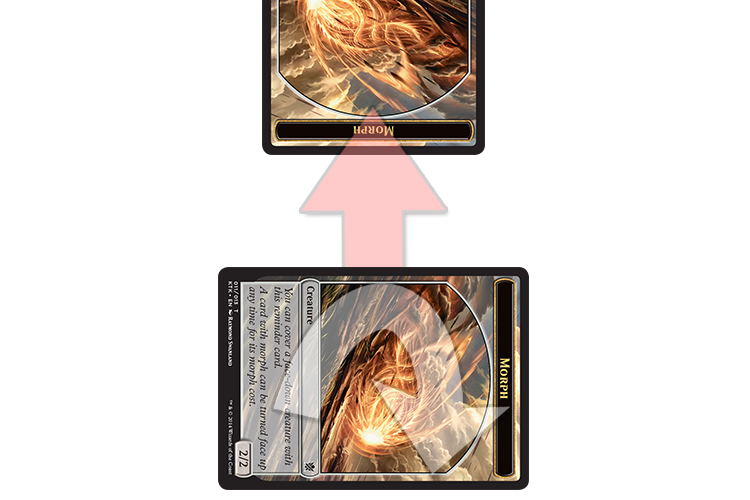

The rules team spent a long time trying to crack this problem, and then one day found the perfect solution. What if the game just defined the stats of a face-down creature? If all of them were the same, you didn't have to know what was on the other side to figure out game state situations. The rules team then realized that this new rules technology would enable an entirely new mechanic. Imagine cards that you played face-down from your hand, and then you could later pay mana to turn them face-up. If this was a whole mechanic, the opponent wouldn't even know which creature you had until it turned face-up.

Art by Raymond Swanland

The rules team was quite excited with their mechanic which obviously would go onto become morph (at the time, by the way, they called it stealth). They came to R&D to find someone to share their enthusiasm about the mechanic. That someone would be me. No one else was particularly fond of the idea but I saw great potential in it. I did, though, have one small change I suggested. In the rules team original version, you paid two mana and the face-down creature was a 1/1. Feeling that the 1/1 would not be substantial enough to matter on the battlefield, I suggested how about three generic mana and it was a 2/2? (For more on the history of the morph mechanic, feel free to check out "Wait, There's Morph," the article I wrote about the mechanic's design for Morph Week.)

Bear With Me

Flashforward over a decade later. The exploratory design team had been working on

Khans of Tarkir block for close to a year. (Remember the very first exploratory design team—we used to call it

Advanced Planning—was for

Khans of Tarkir block.) We had created the large/small/large, "draft the middle with both large sets" structure and attached the time travel flavor to it. Finally, I had my heart set on using morph as the core mechanic that would warp from set to set as Tarkir changed. Knowing that I wanted to use morph and that it had proven to be a developmentally challenging mechanic in the past, I went and talked to Erik Lauer (the head developer, my equivalent for development).

Erik spent some time looking at how morph had been done developmentally in

Onslaughtblock and then how it was done in

Time Spiralblock. He felt there was probably a way to make it work. His big question was did we want to use morph or did we want to make a new mechanic that was very similar but instead of three mana to cast the 2/2 face-down creature it cost two mana. We nicknamed that mechanic "borph" as in "bear morph" because Bears (or

Grizzly Bears) are slang for a vanilla 2/2. "I'm about to start design," I asked Erik, "Should I be using morph or borph?" Erik said morph.

Grizzly Bears | Art by Zina Saunders

I started up Khans of Tarkir design and, thanks to all the work of the exploratory design team, we managed to do the design faster than we ever had before. We came up with the idea of the factions based around dragon attributes and eventually figured out those factions would be wedge-based. We hashed out that Dragons of Tarkir would be allied-colored pair instead of enemy. We found five guild mechanics. And, finally, we crafted an environment around the morph mechanic such that the very style of how it played would both take advantage of morph existing and interact with it in cool and fun ways.

Things were going great…until I had another conversation with Erik. Now remember that design is a year ahead of development. While I was busy trying to design Khans of Tarkir, Erik was busy bringing the Theros block to life. While I was neck-deep in thinking about Khans of Tarkir, Erik was not. He told me that he was still trying to figure out whether they wanted to use morph or borph. I explained that he and I had talked about it, and he had chosen morph. Erik explained that when I had asked him about it he hadn't had any time to put toward thinking about Khans of Tarkir block. He assumed I was asking him which I thought was more likely to end up in the set. No, I said, I needed to know which to use because design was starting and I was building the entire set around the mechanic. That was a problem, Erik said.

Something on the Side

As a quick aside before continuing: The act of creating

Magic is an ongoing process that we keep refining. Design having to make decisions that will affect development long before development has had any time to think about the issue is a problem that we've spent a lot of time working on. This event was a wake-up call that we had to re-evaluate how we were doing some things—much of which we have, so there's a happy ending long-term.

Horde Ambusher | Art by Tyler Jacobson

Development was very serious about wanting to try out borph. Whichever face-down mechanic we chose was going to be central to the design. Morph and borph lead to different designs. How exactly were we going to solve this problem? Thanks to a lot of factors (exploratory design being the biggest) Khans of Tarkir design was ahead of schedule, so we came up with a pretty radical plan. We would take the existing Khans of Tarkir file (then codenamed "Huey") and copy it making a brand new set called "Phooey." The original Khans of Tarkir file would stay frozen during the length of this experiment in case we later wanted to go back to it. We would then change all the morph to borph in "Phooey" and alter the design around that change.

The original plan was we would take a month to design "Phooey" and see where that took us. Development was on the hook to pay attention (reading over the file and participating in some playtests) so they could make a recommendation whether the felt we should stay with "Phooey" and borph or go back to "Huey" and morph. Yes, our time travel block with an alternate timeline also had in it a set with an alternate timeline.

A Whole New World

We started the design of "

Phooey" by changing all the morph cards in the file to borph cards. We quickly learned that this change had a number of implications:

Issue #1: The Line Had Moved

The design of morph is built around three mana. Borph is built around two. This means that in a morph-heavy set, the three-drops have to get out of the way to make room for morph; while in a borph-heavy set, the two-drops have to get out of the way. We tried to solve this problem by converting as many of our two-drops as possible into three-drops. This line also had an impact in how you could design a borph creature. With morph, you have the option of making a creature that can be played before you get to three mana. With borph, that left only one-drops…and even a large set doesn't have many of those.

Issue #2: The Environment Sped Up

In borph world, everyone had a 2/2 on turn two. Most had a 2/2 on turn three. They sometimes had two 2/2's on turn four. In a faster environment, a 2/2 vanilla two-drop creature is quite playable. A 2/2 vanilla two-drop creature that can later turn into something bigger is very playable. At one point I dubbed borph the "

Kavu Titan mechanic."

[card]KAVU TITAN[/card]

I then realized that borph was even better, because if you chose to play the creature on turn two, you could still have it be the larger version later.

A turn-two 2/2 isn't about sitting back. It's about being aggressive and attacking. The borph mechanic just turned up the clock on the game and made it much more about racing the opponent.

Issue #3: The Creature Curve Warped

Morph tends to inflate the number of three-drops in a set. Borph did the same for two-drops. The problem was that, normally, in a set there are fewer two-drops than three-drops. Add to that the colorless nature of borph and all of a sudden, every player was able to play lots and lots of two-drops regardless of the colors they were playing.

Issue #4: Face-Down Creatures Got Turned -Up Less

As the environment sped up and the game play got more aggressive, fewer and fewer face-down creatures were surviving to a point where you could turn them face-up. In addition, because games were faster, they just lasted fewer turns; which meant players just had access to last mana overall. This didn't just mean they we saw fewer big bodies. It also meant there weren't nearly as many triggers doing interesting effects.

Issue #5: The Non-Face-Down Part of the Creatures Got Worse

A borph creature just has more play value than a morph creature, which meant that each individual card got less cool stuff on the face-up side. The stats got worse, the mana cost got higher, or the borph cost got more expensive. Putting more "power points" into the face-down side took away from what was allowable on the rest of the card.

Issue #6: The Value of the Faction Mechanics Changed

Raid got much more powerful, as the game play was all about attacking. Outlast, in contrast, got significantly worse because giving up an attack had a much greater cost. Prowess suffered, as decks wanted to play more creatures to ensure the aggressive start they needed to race. Ferocious got worse because the creature were smaller overall. The quicker, faster game play led to fewer larger creatures seeing play. Delve had advantages and disadvantages. Advantages because all the dying creatures tended to fill up the graveyard a little faster and a cost-reduction mechanic can often be very valuable when you're trying to get threats out as quickly as possible. Disadvantages because delve cards were on the expensive side and faster games get you to higher costs less frequently.

I should stress that we shifted how the mechanics worked or were costed to help offset the impact of borph. Raid cards got you a little less value while ferocious only required 3 power instead of 4. The entire point of this experiment was to see what happened to the set when you made the change from morph to borph.

Issue #7: The Clans Had Less Individual Identity

When the correct play for every clan was to drop your 2/2 on turn two, it started making them play more similarly. We worked hard to try to keep an identity for each clan, but the style of game play was working against us.

Issue #8: Face-Down Creatures Got Played More

One of the reasons for the change was to try and make the face-down mechanic see more play in both Limited and Constructed. Mission accomplished. As I said above, people were playing not just the borphs in their color but often every borph they opened up/drafted. Making the face-down creatures matter in Limited was always going to be achievable but doing so in Constructed was a tougher challenge. This change definitely encouraged higher-level players to use the mechanic.

Issue #9: The Warlord World Was Even More About Fighting…

One of the goals of

Khans of Tarkir design was to capture the essence of a warlord world by having creature combat play a higher role than normal. Borph world led to a lot of creatures smashing into other creatures.

Issue #10: …But That Fighting Was More of the Same

Yes, more creatures were attacking, but the most common result was a face-down 2/2 running into another face-down 2/2 and both being destroyed. While creature combat was up, it was more monotonous.

Why Did the Check-In Cross The Road?

Our four-week experiment ended up actually lasting six weeks. We were iterating very quickly. One meeting of the week would be making changes and the other was playtesting. If we were going to do this test, we wanted to do it right and we went full throttle in our alternate universe.

When the dust settled, the design team preferred "

Huey" to "

Phooey". Borph mattered more than morph, but with it came a pretty devastating cost. It ran roughshod over a lot of elegant design we had spent a long time crafting. The clan identities had gotten muddier, the face-down creatures were getting turned face-up less, and the game play was faster than we liked.

The developers were more divided. Borph was much easier to make a Constructed mechanic. In the end though, what swayed Erik and others was the fact that the face-down cards were just staying face-down way more often. The cool thing about any face-down mechanic is the surprise of what lies underneath, and that was just happening far less.

I said I wanted to go back to "

Huey" and Erik agreed it was the right call. Along the way, we made numerous changes we liked, so part of switching back was trying to figure out what advancements from "

Phooey" could be made to work in "

Huey".

It's interesting to look back at the "

Phooey" experiment with hindsight. At the time, it was very stressful for me, but I believe

Khans of Tarkir was better for us having done it. Sometimes the best way to understand something is to take it away and experience life without it. Playing "

Phooey" helped me have a better sense about what I valued most in "

Huey".

Art by Jason Chan

Duck, Duck, Duck, Goose

And that, my faithful readers, is the story of the set you didn't know about and will never play. "

Phooey" had a short life, but it was an educational one. As always, I am eager to hear your feedback on today's column. You can write to me through my

email or contact me on any of my social media (

Twitter,

Tumblr,

Google+, and

Instagram).

Until next week, may you learn to appreciate something by taking it away for a while.

It turns out the naming convention had one other by-product. You see, occasionally in the comics an artist would accidentally draw four ducks instead of three, and numerous comics got printed with this mistake. It happened enough times that they actually named the fourth duck, Phooey Duck. So when the codenames became public, I got a lot of jokes from Huey, Dewy & Louie fans about where was the fourth set? Where was "Phooey"? Little did the people making that joke realize there was a "Phooey." It was a real set that, for a little while, looked like it was going to get made.

Today's column is all about "Phooey," the Khans of Tarkir set that no one outside of Wizards has ever heard about.Well, that is, until today. Sit back, my faithful readers, as I am going to tell you a story of the set of "Phooey"—what is was, how it got made, and why it never saw print. Sound fun? Then let's get started.

It turns out the naming convention had one other by-product. You see, occasionally in the comics an artist would accidentally draw four ducks instead of three, and numerous comics got printed with this mistake. It happened enough times that they actually named the fourth duck, Phooey Duck. So when the codenames became public, I got a lot of jokes from Huey, Dewy & Louie fans about where was the fourth set? Where was "Phooey"? Little did the people making that joke realize there was a "Phooey." It was a real set that, for a little while, looked like it was going to get made.

Today's column is all about "Phooey," the Khans of Tarkir set that no one outside of Wizards has ever heard about.Well, that is, until today. Sit back, my faithful readers, as I am going to tell you a story of the set of "Phooey"—what is was, how it got made, and why it never saw print. Sound fun? Then let's get started.