The Pit and the Pendulum

Anyone who reads me regularly knows I love my metaphors. I find them an important tool for explaining things in an approachable way. As someone who constantly writes about Magic, that means I make a lot of metaphors about the game—but one metaphor has been used by me more than any other: the idea that Magic is like a pendulum.

Click to read just a few examples

"I do believe that we are at a low ebb right now, and as I love to say, I believe the pendulum will eventually swing the other way."

—"Inquiring Minds Want to Know, Part 2," March 24, 2003

"Probably my favorite metaphor of Magic is that of a pendulum (you know, the metal point on a rope over a sand pit) constantly swinging in an ever-changing pattern. Design's job is to keep pushing the pendulum in new directions, knowing that every aspect will eventually come back to center. Why do I bring up the pendulum metaphor (yet again)?"

—"Come Together," October 6, 2003

"What separates Magic from other games is its ability to constantly shift. And that shift comes from the designers pushing the pendulum in new and different directions."

—"Type 1, Take 2," December 15, 2003

"Magic is a game of ebb and flow. I always describe it as a pendulum that R&D keeps pushing in different directions. This ever-changing quality means that at any one moment in time some aspects of the game are weaker or stronger than the norm."

—"Up and Down," December 6, 2004

"The pendulum can swing, but only so far."

—"Once More with Feeling," August 1, 2005

"I've often explained Magic as a perpetually swinging pendulum. From year to year, the designers choose different elements of the game to focus on.

—"City Planning, Part II," September 12, 2005

"But the pendulum always swings back and I felt it was important that Time Spiral block return to our traditional handling of block keywords—that is, that they evolve over the course of the block."

—"The Future Is Now, Part III," April 23, 2007

"The pendulum always swings. Time Spiral block made many deliberate choices that we felt would shock the audience."

—"State of Design 2007," August 13, 2007

"While design came into Lorwyn with its goals, so too did the creative team. Metal world, Japanese-inspired world, city world, post-apocalyptic world—each of these environments had their own distinctive stamp, but none of them were solidly grounded in traditional fantasy. Combine that with a desire to swing the pendulum back from the crazy chaotic feel of Time Spiral block and you have a sense of where the creative team wanted to go."

—"A Lorwyn/Lorwyn Situation," September 10, 2007

"I always talk about how we like to swing the pendulum to alter how formats work from year to year. Lorwyn Draft is quite different from Time Spiral Draft in that the basic strategies are a little more linear."

—"Lorwyn One for the Team," September 24, 2007

"The good news is that Magic is all about change. What this means is that we are constantly pushing the pendulum in new directions."

—"Innovate Is Enough (Or Is It?)", February 18, 2008

"I always talk about how Magic design is about constantly pushing the pendulum in a new direction."

—"State of Design 2008," September 1, 2008

"Now it's time for the pendulum to swing away for a while."

—"Tweet Talk," June 8, 2009

"But as with any aspect of the game, the pendulum is allowed to swing."

—"Drop and Give Me 2010," July 6, 2009

"To all the control lovers out there, don't worry—the pendulum will swing like it always does."

—"Feeling Blue," July 13, 2009

"For the same reason that we take away the other beloved things: Magic works best when the pendulum swings, having things go in and out of sets."

—"Achieving Zendikar, Part 1," September 7, 2009

"Another way to think about it is that Limited allows you to better experience the swings of the pendulum."

—"You Had Me at Eldrazi," April 26, 2010

"While I like to push the pendulum in all areas of the game, including the speed of the Limited environment, I believe Zendikar pushed the pendulum farther than it should have."

—"State of Design 2010," September 27, 2010

"The pendulum will swing, but in general, we don't want all the mechanics in a set being linear or modular."

—"I Want to Threshold Your Hand (Or Possibly My Artifacts)," October 18, 2010

"The pendulum has swung back a bit and we are more willing to do slightly more complicated mechanics at higher rarities."

—"The Mighty Core," July 18, 2011

"We try to make sure the pendulum is swinging in different directions so that the feel of the game is shifting, but we also watch our block themes to make sure that they have synergy with the sets before and after."

—"A Modern Sensibility," October 31, 2011

"As I like to call it, we push the pendulum so the game keeps swinging into new territories."

—"Old vs. New," February 13, 2012

"Magic has a bit easier of a time because we allow ourselves to push our pendulum pretty hard in a new direction each fall."

—"Duel's Paradise," June 11, 2012

"Another reason it's important for cards to rotate out, as well as in, is without the exodus it would become harder and harder to push the pendulum in new directions."

—"Setting the Standard," August 6, 2012

"When the pendulum swings back to its neutral position, white will return [to] doing what it always does."

—"Unanswered Questions: Theros," November 14, 2013

"When I design a Magic set, I have multiple goals in mind. I'm trying to make a fun game experience. I'm trying to push the pendulum in a new direction."

—"Story Time," July 28, 2014

"Theros block had been top-down design based on Greek mythology, and I was interested in pushing the pendulum to the other end of the spectrum."

—"Khan Do Attitude, Part 2," September 8, 2014

"I use the pendulum metaphor because there is a center to the game and we want to make sure the game doesn't drift, long term, and keeps coming back to the center."

—"Bleeding Cool," April 6, 2015

"I believe experienced players had a lot of fun with Khans of Tarkir block and the pendulum of complexity needs to swing, but I also believe this was a harder than average block for a new player to start with and we have to remember that there are always new players."

—"State of Design 2015," August 24, 2015

For today's column, I want to dive into this metaphor and talk about how it came about, why it's so apt, and why it's become the go-to metaphor for all of R&D, in the Pit and beyond.

I Never Metaphor I Didn't Like

The point of a good metaphor is to take a complex idea and attach it to something that the average person is more familiar with. That way, the complexity is lessened because you're using the audience's pre-existing knowledge as a teaching tool. Rather than starting from scratch, you're building on information the audience already has.

What this means is that designing a good metaphor requires two things. First, the item in question has to be something the audience knows. I could have the best metaphor in the world, but if the audience is unfamiliar with the item the metaphor is built around, it doesn't make use of the necessary pre-existing knowledge and thus won't work. Second, I need the metaphorical item and the original item to have enough similarities that you can make a solid connection. If the metaphor is too strained, the audience often won't be able to make the bridge from the metaphor to the real item and thus, again, it won't work.

My earliest involvement with Wizards of the Coast was through my writing. I was a regular contributor to The Duelist (a Magic-based magazine Wizards used to produce) and was often called upon to write a lot of exploratory text for different sections of the company. As most of this required me teaching things, I started looking around for good metaphors for the game.

Fast forward a year or two and I was working in R&D. I was not just explaining how to play Magic, I was writing about the behind the scenes of how we made Magic. I, once again, started looking for metaphors, but this time more about the inner workings of the game. In April of this year, I wrote an article called "Push and Pull" where I talked about the core tension of Magic design: the fact that the game wants to both constantly evolve and stay the same. I needed to find a metaphor that captured this tension, that the game was in constant motion yet mostly stayed in the same place.

When I'm looking for a metaphor, one of the exercises I often go through is to figure out what parts I'm trying to replicate in my metaphorical item. What exactly about Magic design was I trying to capture? Here were the main points: (with some stories about my college days as a lead in)

- Magic has an unmovable core

In college (and for a few years after), I used to do stand-up comedy. After spending hours and hours doing open mics, I came to learn what the essence of stand-up comedy was all about. It wasn't about jokes. It was about having a voice, about exhibiting a filter through which you comically saw the world. If you had a clean, clear voice, the jokes would come, but more importantly, the audience would be able to wrap their mind around you. You would have a core that your comic persona could be built around.

Magic succeeded because Richard Garfield, Magic's creator, found its voice. It wasn't just a game about dueling wizards. Magic had an ethos. The five colors each had their own philosophy that meant something not just in isolation but in conjunction with one another. Both the mechanics and the flavor were extensions of the color wheel. The persona of the game was built around this core.

Much has changed since Magic premiered in 1993, but the core has not. We have fine-tuned the philosophies, we have massaged the mechanical implementation, we have played with how we visually represent the colors, but the core essence of what each color stands for, of what each color is about, of what each color represents, has not changed.

This means that the metaphor had to take into account that Magic is built around something that is locked in place. The game has a center and that center does not move.

- Magic constantly contrasts with what came before it

Also in college, I started an improvisation troupe called Uncontrolled Substance. For those who have never seen an improv troupe perform, here's how it works. Some number of the troupe gets up on stage and asks the audience for suggestions based on one or more topics (a relationship, a location, an emotion, etc.) and then you perform a skit made up on the spot incorporating those suggestions. An improv show usually lasts from 60 to 90 minutes and has numerous of these improvised skits back-to-back.

Part of my job as the person running the troupe was structuring the shows. I had to pick which improv formats (different ones asked for different inputs and led to different styles of skits) happened in which order with which troupe members. One of the things I learned quickly is that the key to success when creating an improv show was to make each skit different from the one that came before it.

Improv formats fall into a number of categories. What you wanted was to separate out the ones that were similar from one another. If one skit, for example, asked for the audience to yell out a large number of suggestions from one topic (like say genres of television and film) that got written down and yelled out during the skit, you didn't want to put another like that right after. Likewise, you wanted to mix up which actors you were using and even how many actors were used per skit. Novelty was key in making the show feel fresh.

Magic blocks work in a similar fashion. If Block A is about one aspect of the game, Block B, which follows it, wants to be about something different. This applies not just to the mechanics but also to the creative side. There's a reason Kaladesh block is bright and sunny following Shadows over Innistrad block, which was dark and bleak.

This constant change of focus has another important purpose in addition to novelty. Development is responsible for providing a balanced game environment while making sure that every new set has something to contribute. To do this, they have created what I have dubbed the Escher stairwell, after M.C. Escher's famous lithograph, "Ascending and Descending."

Each set takes some element of the game and pushes its power level. To keep from creating power creep (each expansion is just more powerful than the one that preceded it), development keeps the power level static by reducing the power of other aspects of the game. As attention is drawn to the powerful aspects, it creates this illusion that the stairwell is constantly going up when in reality it's staying roughly the same.

All this means the metaphor had to explain a system that is always in flux and never stays static.

- Magic is a relational, dynamic system

In college, I also did a bunch of playwriting. I belonged to a group called Stage Troupe that was the extracurricular acting organization at Boston University. I was a bit of an outsider, so when I would write a play, I usually got minimal financial support from Stage Troupe. I had access to the students for auditions, but I had to mostly self-finance my plays, often by going to different organizations around the university and getting a bunch of them to each give me a small amount of funding.

Because of this, my budgets were always very tight. That meant that I tended to write to my limitations. I didn't have enough money for more than one simple set, so my plays would take place at a single location. The actors didn't cost anything so I was able to have larger casts if I wanted. This is probably where I first encountered the idea that restrictions breed creativity, because I found that having to write with limitations actually provided me with direction.

Magic design has a similar quality to it, not by lack of funds but rather by the need to move away from where we had just been. There have been many times where I have had to avoid the more obvious answer because a recent set went down that path. Similarly, sometimes we find ourselves pushed in a certain direction specifically because we were trying to move away from a different direction. There are many different ways to do a steampunk-inspired world, for example. The push toward optimism and brightness was a direct result from moving away from pessimism and darkness.

What this means for the metaphor was that the movement between sets wasn't random; it was relational. We needed an item where the movement had fluidity, where all the movement could be looked at sequentially as a larger pattern.

- Magic has limits on how far it can go

Still during college, I started a writer's workshop—a means by which a group of writers could write, direct, and act in their own series of sketches. (Yes, there's an ongoing theme in my life of not having much downtime.) One of the rules I set up was that each individual workshop had to have a theme. The theme could be loose and the writers were allowed some leeway to stretch the theme, but there were limits and sometimes a sketch was considered out of bounds for a particular workshop.

The reason I'd made the theme a mandatory component was that I wanted each workshop to have an identity, and I knew if there weren't constraints, the shows would lose their cohesion. It's very easy when you focus on the micro to not see what impact your choices have on the macro (or in more common terms, you can't see the forest for the trees). I've often talked about how limits can help you with creativity, but they're also good for helping set boundaries to keep you from drifting too far away from your core.

In Magic, what this means is that there's a limit to how far away we want the game to move from its center. There comes a point where you're different enough that the game starts losing its identity. I could take Magic's rules and make a functioning game that no one would recognize as Magic, but what would I have accomplished? The game being recognizable is a key element of what makes it something players stick with. They need enough familiarity to create a sense of comfort.

What all this means is that the game can change but only so much. There are limits. And that means our metaphor has to take this limitation into account.

Going with the Swing

To find the metaphor, I started with these four qualities:

- The item has to have an unmovable core.

- It has to constantly move to new spaces.

- The movement has to be relational to previous movement.

- There are limitations to how far away it can move.

Number 1 implies that the item in question is attached to something. Numbers 2 and 3 require that it's capable of movement. Number 4 restricts that movement. This led me to an object that is attached on one side but unhindered on the other. There are weapons, for example, the wielder holds that deal damage with movable parts. There are also static types of transportation like a ski lift that stay on a track but move.

The part I kept having problems with was number 3. All the things I was coming up with moved, but not along a very discernable path. If I wanted the movement to be relational, I needed a force that was constant in how it functioned. That led me to the idea of gravity. Gravity was constant without necessarily having to be directional.

I needed an object that was attached on top that I dropped and then allowed gravity to control its movement. After working through a bunch of different items (I really wanted to make a yo-yo work), I ended up with the idea of the pendulum.

Let's examine it against the four qualities:

The item has to have an unmovable core.

A pendulum is attached at the top. Gravity pulls downward. That means there was always going to be a center, one that the pendulum would keep returning to.

It has to constantly move to new spaces.

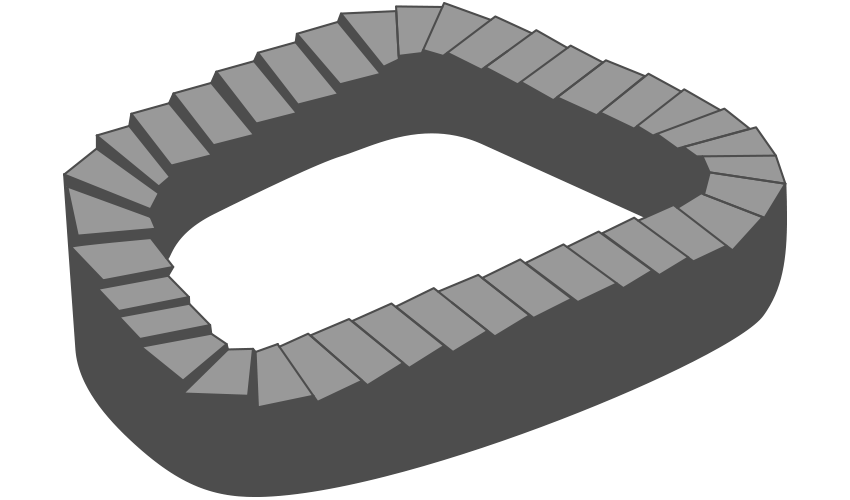

A pendulum is defined by movement. In fact, most pendulums have a component that traces its path into the substance below it, usually sand.

The movement has to be relational to previous movement.

A pendulum is controlled by its locked center and gravity. The end result is that a pendulum is always carried away from where it last went.

There are limitations to how far away it can move.

A pendulum can never move farther than the length of its rope allows. By definition of the factors at play, a pendulum has a defined outer limit.

Good Ideas Are Contagious

Once I found the pendulum metaphor, I started using it both externally (in articles) and internally (in meetings and internal documents). I found that it did a good job of hitting both requirements for a metaphor—most people knew what a pendulum was and how it functioned, and the relationship between Magic's inner workings and that of a pendulum was close enough that people could make the logical leap.

R&D took quickly to the metaphor, not just for mechanics but for other aspects of the game as well, such as creative. In fact, when I was finding all my quotes from the website above, I discovered that over half the uses weren't by me. The public also took a liking to the metaphor and it's still something that shows up when players discuss the dynamic of change within the game.

And that, my faithful readers, is how the pendulum metaphor came to be.

This was a different kind of article, so I'm curious what you all thought of it. As always, you can email your thoughts or talk to me through any of my social media accounts (Twitter, Tumblr, Google+, and Instagram).

Join me next week when it's time for another Topical Blend.

Until then, may you know the joy of finding an apt metaphor.

"Drive to Work #386—Preview Season"

In this podcast I talk about what it's like from our side knowing things that the players don't and watching what happens as the public learns about new sets.

"Drive to Work #387—Urza's Destiny, Part 1"

This is part one (of four) in my series on the design of Urza's Destiny.

- Episode 385 Council of Colors (24.9 MB)

- Episode 384 Group Creation (25.7 MB)

- Episode 383 20 Lessons: Customization (25.9 MB)