The Un-Ending Saga, Part 2

Last week I started telling Unstable's design story, but I began early because I had a lot of story to tell. Today is the beginning of previews, so today I get to continue the story but also show you preview cards from the set. (And I have a lot of them today.) Today's section of the story is about the largest feature of the set—Contraptions! The story of their design is a long and winding one, and I'm excited that I finally get to tell it.

Before I explain how the mechanic came about, I want to start by walking you through what the mechanic is and how it works. It's a little on the complex side, so bear with me.

First, and foremost, let me explain what Contraptions are. I often talk about how Un- sets explore the future and stretch into areas that current black-border Magic does not. Contraptions fall firmly in this category. Contraptions are cards from their own deck, what is called a Contraption deck. It has a different back.

This back both explains what happens when you assemble a Contraption and is used as a guide to help with Contraption placement. When Contraptions are assembled, they go onto the battlefield as artifacts, but in a specific configuration. They are put into one of three vertical columns called sprockets. The three sprockets are called Sprocket 1, Sprocket 2, and Sprocket 3. The card back helps with this.

Each turn, one of the three sprockets cranks, which means that every Contraption in that column is going to activate. You're allowed to have the Contraption effects go off in whatever order you wish. Also, using Contraptions is optional, so if it's not in your interest to use an effect, you can just skip it. The turn after you assemble your first Contraption, you crank Sprocket 1. The next turn you crank Sprocket 2. The next turn you crank Sprocket 3. And then the next turn, you're back to Sprocket 1. This loop goes on for as long as the game lasts.

To keep track of which sprocket you're on, there's a CRANK! counter that goes onto the back of your Contraption deck to mark it. At the beginning of each turn, you advance the CRANK! Counter to the next sprocket and it activates all the Contraptions in the column. The CRANK! Counter starts on Sprocket 3, so that the first sprocket to get cranked is Sprocket 1.

Let's walk through an example. Imagine your opponent has a pesky creature you want to get rid of, so you cast Finders, Keepers.

It destroys the creature and then assembles a Contraption. You draw and reveal the top card of your Contraption deck and it's Hard Hat Area.

You now have a choice of where to assemble it—in Sprocket 1, Sprocket 2, or Sprocket 3. You choose Sprocket 1 because that will activate next turn. At the beginning of your next turn, you control a Contraption, so you move the CRANK! counter from Sprocket 3 to Sprocket 1 and crank it. This makes the Hard Hat Area activate. You roll two dice and get a 5 and a 4. The difference is 1, so you get to assemble one Contraption. You draw and reveal the top card of your Contraption deck and it's Genetic Recombinator.

You now have a choice of which sprocket to assemble it in. You might choose Sprocket 2, as that would make it go off the fastest, but let's say you have no creatures on the battlefield. Maybe you want to put it in Sprocket 3, allowing you to cast creatures on this and the next turn and get the most out of the effect. (Note that Genetic Recombinator says "up to two," so you could still use it if you only have one creature.) Looking at your hand, you choose Sprocket 2. Then this turn, you cast Kindly Cognician.

This then allows you to cast Steamflogger of the Month for just four mana.

When Steamflogger of the Month enters the battlefield, you get to assemble a Contraption for each Contraption you have. As you have two (Hard Hat Area and Genetic Recombinator), you get to assemble two new Contraptions. You draw and reveal the top two cards of your Contraption deck, which are Dogsnail Engine and Bee-Bee Gun.

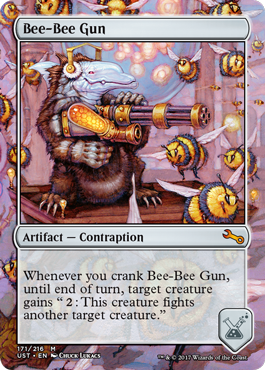

Dogsnail Engine lets you gain life equal to the greatest power among creatures you have on the battlefield. That combos nicely with Genetic Recombinator, so you put it in Sprocket 2. Bee-Bee Gun lets you fight with one of your creatures. It also combos nicely with Genetic Recombinator, but your opponent doesn't have any creatures on the battlefield, as you destroyed their only one with Finders, Keepers. You have a choice between putting it in Sprocket 2 for the synergy or putting it in another sprocket to try and up the chances that you get to fight something sooner (or maybe just to discourage your opponent from playing a creature for an extra turn). Let's say you choose the latter and put it into Sprocket 3.

On your next upkeep, you advance the CRANK! counter to Sprocket 2 and crank it. Genetic Recombinator and Dogsnail Engine are in this sprocket, so you get to decide the order of the effects. You choose to let Genetic Recombinator's effect resolve first and make your Kindly Cognician a 3/5 and your Steamflogger of the Month a 5/5. Then you let Dogsnail Engine resolve to gain you 5 life.

On your next upkeep, you advance the CRANK! counter to Sprocket 3 and crank it. Bee-Bee Gun is in this sprocket, so you can have your Steamflogger of the Month fight one of the creatures your opponent played last turn.

There are 45 Contraptions in Unstable, nine per faction. (The symbols of each faction are in the bottom right-hand corner and, for game purposes, count as watermarks.) They are common, uncommon, rare, and mythic rare. Each booster pack has two. (Note I am talking about Contraptions and not cards that assemble Contraptions.) In Limited, you may play with whatever combination of Contraptions you open or draft. You're not required to play them all and you can play duplicates. In Constructed, you must play a minimum of fifteen Contraptions and you may only have one of each.

I know there are many questions you have about how Contraptions work. Be sure to check out the Unstable mechanics article so you can get all those questions answered.

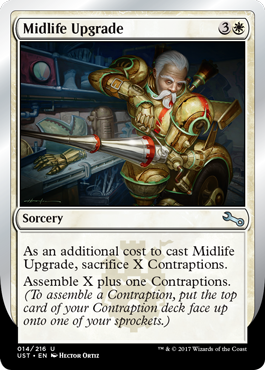

Now that I've explained what Contraptions are, I want to move on to talk about how they got designed. Before I do that, though, I have one last Contraption-related preview card to show you. It's a sorcery called Midlife Upgrade.

Hopefully cards like Kindly Cognician and Midlife Upgrade demonstrate how you might be able to build a Contraption-themed deck.

Building Up Steamflogger

When last we left our story, I was intrigued by the idea that silver-bordered design space might allow me to capture the essence of Contraptions. Let me walk through some of my problems when I tried to solve Contraptions in black-border Magic. Steamflogger Boss was made as a joke card; when we fleshed it out originally, we weren't trying to create something we planned on following up on. Contraptions were defined as an artifact subtype and Steamflogger Boss implied that there were creatures of the subtype Rigger that could assemble Contraptions. (Note that Riggers did the assembling and not the player.)

Probably the biggest limitation though was the word Contraption itself. According to my dictionary, a contraption is "a piece of equipment or machinery that is unusual or strange." The fact that it was assembled implied to me that it was made of multiple pieces that were somehow being forced together to create a larger machine. My mind kept going to Rube Goldberg machines.

That meant that I needed to have multiple artifacts that came together in some way. I experimented with energy, but the connection between the artifacts felt tangential. I tried making artifacts with the subtype Contraption that had the option of adding counters to other Contraptions instead of being cast, but it resulted in always having just one card on the battlefield with a lot of counters; it just didn't feel like a machine. I played around with the link mechanic based on things like S.N.O.T. from Unhinged where cards pieced together (discussed in this article), but the rules didn't cooperate. (Link would be the inspiration for another mechanic in Unstable, but I'll talk about that next week.) I messed around in meld space where you had different pieces and you needed to play them in conjunction with one another, but the gameplay was frustrating.

In about a five-year span, I experimented with 50-some different mechanical executions. They mostly fell into two camps. Either they had a glimmer of hope in that they captured some of what the idea of assembling Contraptions wanted but they didn't work in the current rules, or they worked within the rules and just felt like kind of blah. Yeah, assembling a Contraption could mean tutor (go into your library and get) or impulse (search the top N cards of your library) for an artifact with the subtype Contraption, but that wasn't delivering on the crazy promise of Steamflogger Boss. If I was going to capture the essence of Contraptions, I felt like I had to be trying something amazing and not just playing it safe.

So, when the idea came up in the Unstable meeting that maybe Contraptions could be a silver-border thing, I was excited to explore what that might mean. Interestingly, my brain went to fighting robots.

A Smashing Good Time

For this part of the story, we have to go back to the year 1993. I had recently discovered Magic and was blown away by the concept of a trading card game. My game designer brain was intrigued by the idea of what other trading card game designs there were. What I was most interested in was finding an execution that was as far away from Magic as possible to see what other nooks and crannies the new game genre allowed. The idea I latched onto was cards that cared about where they existed in relation to other cards, something Magic didn't touch upon.

The idea was that you would start with a single card in play and that you would attach new cards to that initial card, but some elements of the card would dictate how and where things could connect. The theme I ended up with was robots, where the first card represented the core of the robot. Different cores would represent different systems. Then each core allowed you to add components to them—arms, legs, weapons, elements for movement, defenses, etc.

As the game progressed, you would be building a robot that would be made up of a series of cards connected together. At some point in the game, the different robots would start fighting with one another. Because they were made up of parts, robots could get damaged and lose certain functionality without losing the whole robot.

I called the game Qubit (this was a few years before the quantum computing term was coined) because I had come up with a cute backstory for the game. The game took place in the future, where humans had taken to space. They had discovered a safe, efficient energy resource called a Qubit. The creation of Qubits thus was very important, which meant there was a lot of motivation to figure out how to make Qubits quicker. To help solve this problem, a rich woman started a yearly competition anyone could enter. The goal was to be the first person to have your machine to make 50 Qubits.

In the early years of the competition, people would haul out their Qubit-making machines and rush to be the first to get to 50. Then one year, someone figured out that as the goal of the competition was to be the first to make 50 Qubits, they could win by simply destroying all the other machines first and then make Qubits at their leisure. Fast-forward 20 years and the competition had turned into a giant robot battle.

The point of the game was to make 50 Qubits, but really it was a reason to fight with robots. The game was won when you made your 50 Qubits or all the other robots were destroyed.

I was in the middle of making Qubit when I got hired by Wizards, so it was never completed.

Qubit is where my brain went when silver-border Magic was made available for Contraptions. I wanted you to assemble a Contraption by putting together different pieces. That was exactly what Qubit did.

The Making of the Making of the Machine

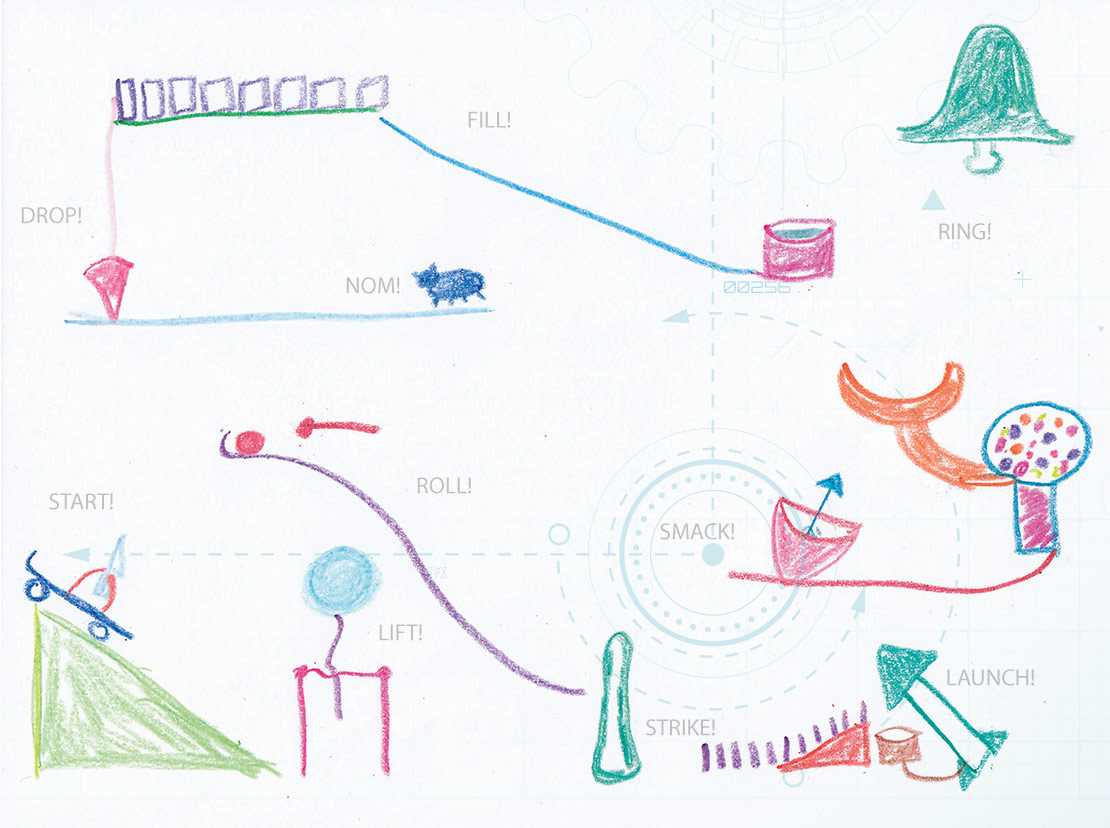

The earliest version of Contraptions started with a card representing the hub (similar to what the back of the Contraption deck looks like). The idea was that as soon as you assembled your first Contraption, you brought out the hub. Your Contraption could then be attached to the hub on the top, right, bottom, or left. Different Contraptions had different connectors so they could be connected in different ways. Then, as long as there was at least one Contraption connected, the hub started working. On the first turn, everything connected to the top of the hub would go off. On the second turn, everything connected to the right. On the next turn, the bottom. Then, the left. And finally, you start over with the top. In order for this all to work, though, the Contraptions would have to be in their own deck.

After the first playtest, I was very excited. We finally had something that felt like a Contraption. You had pieces and you slowly put them together. The pieces could synergize to make a unique machine, something that would change from game to game. It was the first time I had made a mechanic that felt like it truly lived up to the idea of assembling Contraptions.

As we played with this version, we started to find some problems. First was the limitation of where cards could be placed. Too often you'd assemble a Contraption only for there to be no place to put it. Contraptions are hard enough to assemble that having any go to waste felt bad. The second problem was that having things happen every four turns was just a little bit too slow. Third, the physical placement of the cards was taking up a lot of room.

So, we changed from a system of four to a system of three. With that move, we decided it was easier to lay out the Contraptions in columns rather than around the hub. This also tightened up the Contraption play space a little. Also, we removed all placement restrictions. Any Contraption could be placed in any column. This allowed for more strategy and more combo potential. It didn't take a lot of playtesting to realize that this new version was a significant improvement.

Just the Factions, Ma'am

The next step was figuring out what the Contraptions did. The goal was to have small to medium effects that could combine together to make larger things happen. We also decided that we wanted to have different cards for each of the five factions. It was important for each faction to have a different feel.

Order of the Widget

The Order of the Widget Contraptions do one of three things:

- They enhance a creature in some way while also turning it into an artifact.

- They make artifacts.

- They have effects that scale with the number of artifacts you control.

These effects play into their flavor of self-enhancement and their love of artifacts.

Agents of S.N.E.A.K.

The Agents of S.N.E.A.K. Contraptions do one of four things:

- They mess with information (drawing you cards or making your opponent discard cards).

- They make creatures deadlier or harder to block.

- They make creature tokens.

- They have effects that scale with the number of creatures you control.

These effects all have a "spy" feel to them.

League of Dastardly Doom

The League of Dastardly Doom Contraptions do one of three things:

- They destroy, damage, or weaken things, including players.

- They interact with the graveyard.

- They have effects that scale with the number of creature cards in the opponent's graveyard.

These effects tend to be destructive and mean.

Goblin Explosioneers

The Goblin Explosioneers Contraptions do one of three things:

- They enhance creatures in a way that encourages attacking.

- They cause chaotic things to happen.

- They have effects based on rolling two six-sided dice and caring about the difference.

These effects tend to play into the chaotic nature of the Goblins.

Crossbreed Labs

The Crossbreed Labs Contraptions do one of three things:

- They enhance creatures in different ways, always making them bigger.

- They help you get or cast more creatures.

- They have effects based on the power of target creature you control.

These effects tend to play into the creature-building flavor of the faction.

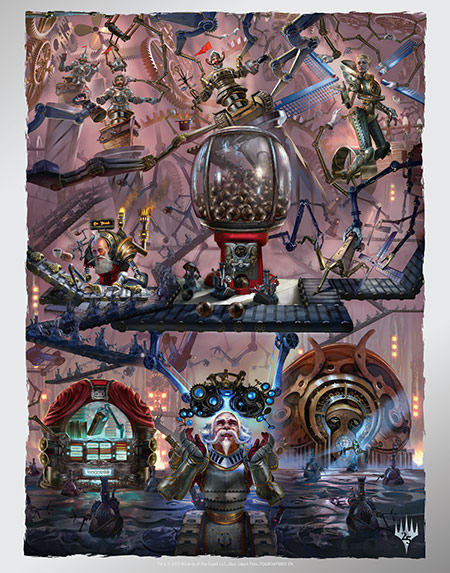

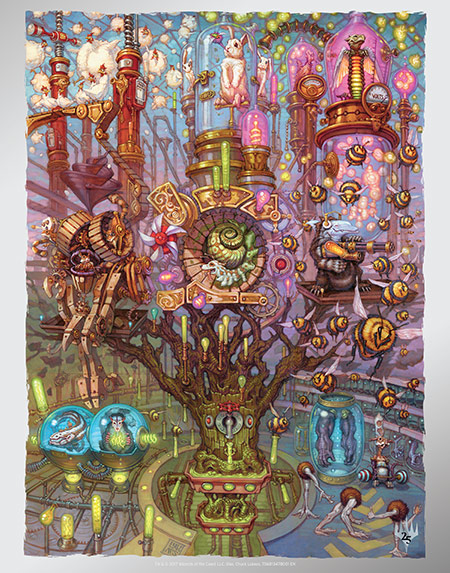

We originally had 50 Contraptions, ten per faction, but Dawn Murin, Unstable's art director, came up with a cool idea of how to illustrate the cards. Each faction's Contraptions were given to an artist, who made a giant illustration combining nine different Contraptions into a three-by-three grid, meaning if you lay out all the cards correctly, they connect to make a giant picture. Note that like the basic lands in Unstable, the Contraptions are borderless. This required us to go down from ten Contraptions per guild to nine.

Here are the five pieces of artwork for the five factions' Contraptions. These five illustrations will be available as prizes from in-store events December 9–10. (So check with your local store to see how you can win one!)

We spent a bunch of time trying to figure out how exactly players got the Contraptions, and ended up dedicating two slots per booster to them. One of the cool things about drafting Unstable is that the Contraptions are a resource that you must draft, so keep track of how many cards you draft that assemble Contraptions and make sure you're picking up enough Contraptions to go along with them.

I Love It When a Contraption Comes Together

And that is the story of Contraptions and their journey through the design of Unstable. There are a lot of other things going on in the set, but you're going to have to wait until next week for me to talk about what they are and how they ended up in Unstable. Wait, I can do better than that. Maybe I should end today's column by whetting your appetite for some of the cool kinds of things we're doing in the set by previewing one last card. This is one of my favorite designs, so I'm excited to show it to you.

Click here to meet Hangman!

Hopefully today's previews have given you a glimpse into the fun that awaits you in Unstable.

As I've been working on Contraptions for so many years, I'm extra eager to hear feedback on the mechanic (and today's article about it). You can email me or talk to me through any of my social media accounts (Twitter, Tumblr, Google+, and Instagram).

Join me next week for the third and final piece of the Unstable design story.

Until then, may you know the joy of finally doing something that you've talked about doing for so long.

#486: Getting Unstable Made

#486: Getting Unstable Made

31:39

I'm joined by carpooling guest Mark Purvis, Magic senior brand director, to talk about how we took a product that no one at Wizards was asking for us to make, Unstable, and got it all the way to print.

#487: Pitching

#487: Pitching

33:36

An important skill is selling your ideas live in a meeting. In this podcast, I talk about how to deliver a good pitch.

- Episode 485 HASCON 2017 (24.5 MB)

- Episode 484 Early Magic Evolution (22.2 MB)

- Episode 483 Ixalan, Part 3 (21.0 MB)