Risky Business

"Only those who will risk going too far can possibly find out how far one can go."

—T.S. Eliot

You're playing a game of Magic against an aggressive white-black deck, and the situation looks dire. Your opponent, Olivier, has decimated your board down to just a single 3/3, and then he attacks with everything.

You run through the potential options in your head. You can't block his two creatures that are swinging in since they have evasion in some way.

You think for a moment. You pick up the one remaining card in your hand: a 4-damage burn spell.

You can use this to take out one of his attacking creatures, stemming the tide. If you block and burn his guy, the board is fairly clear. If he doesn't have a follow-up play, you might be able to climb back into the game. It's a safe play.

Then you glance at your opponent's life total. Seven.

Suddenly, another thought comes into your head. You nod knowingly. You take a breath.

"Char you."

You untap, and...

This risk paid off big time for Craig Jones, creating perhaps one of the most famous moments in the entire Pro Tour. This is far from the first time that topdeck has been referenced in an article like this, and I'm sure it won't be the last. It's such a marvelous example of correctly taking a risk.

But when is it right to take risks? When should you play it safe?

While it's impossible to say for sure without knowing the exact situation, there are some good rules of thumb that will usually guide you to the right place.

Let's take a look at them today.

The Risk Principle

Before going further, it's important to nail down one thing: the guiding principle behind taking risks.

The principle is this: If you're in a strong position, you should take fewer risks. If you're in a weak position, you should take more risks.

Now, more than just games, this is true in life.

Interviewing for a job you're really unqualified for? It's okay to tell a story that could make you look really good or really bad depending on how they take it.

Interviewing for a job you're a slam-dunk fit for? Play it safe.

Do you know the most about basketball out of all your friends and are filling out your group's March Madness bracket? Go with the safe picks your wealth of knowledge tells you.

Filling out the same bracket and don't know as much about basketball as everybody else? Make some unusual calls to see if you can spike a victory.

And as true as it is in life, it's also a prominent part of Magic. The further behind you are, the larger risks you should take, since you're going to need to help them pay off. The further ahead you are, the safer you should play it, since the game generally favors you.

So, what are some times when you might want to take risks? What kinds of things are factors?

Well...

Risky Payouts

Think of risks like an investment. An "even payout" is when the size of the risk is concordant to the result. Small risks yielding small rewards, and big risks yielding big rewards.

However, when the sizes are not concordant is a time when you really need to pay attention.

Let's take a look at the card Gamble (appropriately named!), recently reprinted in Eternal Masters, as a great example:

You have Deceiver Exarch on the battlefield and need to find a Splinter Twin to go off with your combo. But there's a problem: you only have one other card in your hand, and there's only one Splinter Twin left in your deck.

Should you cast Gamble this turn?

Let's say your opponent has no cards in their hand and no creatures on the battlefield. In this case, you are taking a pretty big risk: you are saying there's a 50% chance you are just going to remove your chance of comboing your opponent from happening.

What's the reward? The reward is that your opponent doesn't get another turn or two to mount a threatening offensive or make you discard your Gamble. It's very unlikely.

In this case, you would be taking a big risk for very little payoff.

Now let's change the situation slightly. Instead, you know that your opponent just transmuted Muddle the Mixture for Combust. However, they are currently tapped out.

In this situation, it's right to fire off that Gamble! If you let them untap, you're going to have to try and navigate to a position where you can somehow land a future Splinter Twin on your Exarch while your opponent has Combust mana untapped. It's not impossible—but it's unlikely. I'd much rather take winning on the spot half the time over trying to make that happen.

Mulling Over Risk

Sometimes, entire matchups are favorable or unfavorable. This view can entirely change how you approach the matchup—and how you mulligan as a result.

Let's say you're playing Modern Urzatron versus Modern Affinity.

This matchup is dreadful for you. It's not what you want to play against. They have far too many permanents that they can assemble too quickly. You're on the draw, and, to make matters worse, you mulligan an unkeepable hand to six. The hand you see on six cards is:

This is normally not a great hand. You have a bunch of expensive cards, an Urza's Tower, and a sweeper that requires colored mana. In most matchups, I'd head right down to five cards.

And yet, here I'd keep it.

Here's the deal: this matchup is very unfavorable for you, and going down to five cards isn't going to help matters. This hand has some of the tools you could use to maybe stand a chance, in double Oblivion Stone and Firespout, and the finishers to clean it up.

There's a good chance if you keep that you're going to draw two cards, see no lands, and swiftly perish. But in the instance that you actually do draw a couple running lands—let alone Urzatron lands—you could actually win this game. In a bad matchup like this, it's a risk you should take.

On the flip side, if you are playing against a very favorable matchup, you want to take fewer risks with your mulligans. If you're, say, playing a deck with a ton of life gain against a burn deck, don't keep a one-land hand. You can probably still beat their seven-card hand with your five, or maybe even four.

Outs and Risks

The question you should always be asking yourself at every stage of the game, with every decision you make, is this: "Which play will give me the best chance of winning the game?"

Sometimes, this is obvious. If they're at 2 life and they have no blockers, attack them with a 2/2. But many times, it can involve plays that break your intuition because they go down an odd path—which actually gives you the best chance to win because it plays to your outs.

Let's go back to the example at the beginning of the article from the Pro Tour.

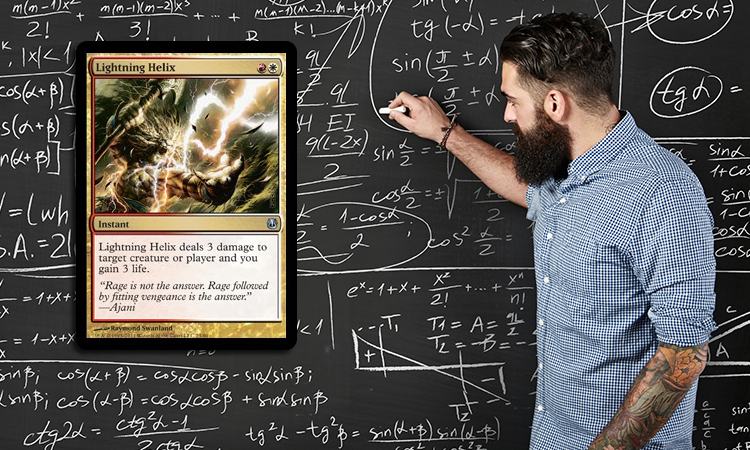

Craig, our eventual Lightning Helixing hero, is certainly not in a good situation here. He has to ask himself, "Which play will give me the best chance of winning the game?"

Well, let's think about it.

To win with the "blocking and Charring a creature" play, Craig needs his opponent to have no more follow-up creatures this turn, and he basically needs to draw a string of creatures that can block and some removal spells to deal with the flying 1/1 token. The chances of Olivier not having more creatures plus drawing a bunch of action from his deck are not great.

On the flip side, let's think about the Char-the-face play. This basically makes it a simple question: you need to deal 3 damage on your next turn. And, though you wouldn't know this just from that short video, Craig's deck has multiple cards that can deal 3 damage.

And consider this: if you burn the creature, think through the next several turns. A card you're probably going to need to climb back into the game is Lightning Helix. So you're basically saying that you might be able to win the game if Olivier draws nothing strong and you draw creatures and Lightning Helix in the next few turns. This is opposed to straight-up winning the game if you can deal 3 damage.

At that point, it starts to become pretty clear: Charring the face is the clear right play.

It can also be useful to consider what your opponent's outs might be and how they can come back from here—and make sure to cut off any chance of that happening.

Let's say you're playing a Sphinx's Revelation Control mirror match. You and your opponent have actually run each other out of resources, and you each have 10 lands on the battlefield and nothing else. Your opponent has no cards in their hand, and you have Dispel in yours.

You draw Sphinx's Revelation for your turn. What do you do?

One of the few ways your opponent can get back into the game after you Revelation is to resolve a Revelation of their own. While it might be tempting to Revelation for the full amount on your main phase and just assume you'll draw an untapped blue source to play, that's a risk not worth taking. Being up six versus seven cards is likely not a meaningful difference—whereas making sure they don't fire one right back could be game-deciding.

Risks on the Side(Board)

Finally, one other area where it can often be appropriate to take risks is with sideboarding.

Let's say that you are playing in a draft, and after Game 1 your deck seemed to be significantly weaker than your opponent's. This means you are at a disadvantage—and should be looking for risks you can take that could pay off.

A common one I do is sideboard out a land for another spell. (Or, if I feel my Draft deck is particularly weak, play one fewer land than I normally would.) If your opponent is going to have better card quality than you, then you're going to need to lean on finding more spells to beat them. (In addition to playing well, of course!)

Similarly, if you think you are extremely advantaged and are likely only going to lose to mana troubles, you can sideboard in an additional land.

Another tactic is to sideboard in cards that are situationally incredible against your opponent's deck. If you're going to be behind against them, you're going to need a powerful option to punch through.

Finally, thinking of the entire tournament scene and more of the metagame, sideboarding can play a huge role there. Sideboarding is, essentially, metagaming distilled into fifteen cards—and sometimes you have to take risks with how you spread those cards.

Let's go back to the Red-Green Urzatron versus Affinity example. Let's say that you just believe the matchup is unsalvageable. You can sideboard in four Ancient Grudges and maybe get to a 30% win rate.

At some point, you just have to let go of winning everything and accept the risk: if you play against Affinity, you're probably going to lose. Spending a bunch of sideboard slots that could be used for shoring up much closer matchups is not worth the little you will move the needle by having cards specifically for Affinity.

Appropriate Risk

Jon Finkel once said, "The right play is the right play, regardless of outcome."

Not every risk, even if it's the right play, will pay off. You will take risks that don't work out. But if it was indeed the right play, then you should be okay making it—and understand that, whether it wins or loses you the game, you'd make the same play over and over again knowing that, on average, it's correct.

Hopefully now you can make those choices with confidence.

In time, and with perspective, appropriate risks just become correct plays. You just have to become accustomed to taking them—and hopefully this sets you on the right path.

There's a lot to think about and discuss here, so if you have any thoughts about this (or anything else, really), I'd love to hear from you. Feel free to contact me on Twitter or Tumblr, where I tend to hang out the most.

If neither of those work for you, you can also reach me through e-mail at BeyondBasicsMagic@gmail.com.

Have a great time playing Magic—and may you take all the right risks. Make it a point to try making some plays you wouldn't normally this week, and see just how far you can go.

Talk with you again next week,

Gavin