Tarkir: Dragonstorm | Episode 3: What the Past Devours

From a distance, the blood ribboning from the dragon's torso made it look like the sky was a slit throat. Gore wept from every part of its hide. A flight of smaller dragons circled the beast like it was already a corpse, nipping, biting, ripping out what chunks they could before the dying beast's massive jaws could catch them. As it flew, more dragons joined the swarm, eager for their share of the feast. Those dragons aligned with the clans of Tarkir tended to do their prey the courtesy of waiting until they were dead before eating them. Their wilder brethren did not.

A feathered, red-scaled horror took its chance. It dove for its bigger counterpart's eye and sank its teeth into the jelly of the organ. Dragons screamed: one in agony, the others triumphant. And down went the hunted behemoth, crashing shoulder first into a tract of tall grass, startling the gazelles and other landbound fauna. The herbivores scattered, a sea of tan-colored bodies bleating with alarm. As more dragons alighted on their still-living prey, the gazelles scattered, breaking into smaller groups, a few veering off alone.

One—a hungry-looking male barely into adulthood—made a break toward the shadow of a massive pine. It ran, panting. It—

Ajani struck, and he struck true: his axe cleaved through the gazelle's neck, sending the head sailing some distance away. He'd been stalking the herd for the better part of the last two hours, finding an animalistic peace in the effort. All his former preoccupation with civility and protecting innocents from harm, and here he was, no better than a beast. The irony wasn't lost on him.

Ajani studied the decapitated animal, blood guttering from the stump of its throat. His old pride would have eaten the gazelle raw. There was a time when he might have done the same: less out of tradition, more because of convenience. But the idea now seemed unconscionable. He'd done so much damage recently, exulted in it, reveled in the carnage he inflicted on the Multiverse. And when he didn't have the excuse of being compelled by Phyrexia, Ajani had chosen selfishness still, demanding Nahiri heal him as if it was a right she had denied him.

How starved he'd been for redemption.

How desperate for forgiveness.

It took Ajani too long to realize his need for atonement had nothing to do with correcting the evil he caused. No, it was to assuage his grief, his guilt, his gluttonous sense of self-loathing. On some level, Ajani had hoped that if he did enough good, it would expunge from his soul all the sins he committed while he was Elesh Norn's slavish little pet.

All of which is to say, whatever tolerance Ajani had for senseless death was gone now. The least he could do for the gazelle was ensure its corpse was handled with dignity. With care, Ajani slung the corpse over his shoulder, fitting it between his neck and the golden epaulet he wore, and began the long walk home to his hut in the wilderness.

Behind him, carrion birds gathered in the sky, a spiral of black wings like a warning of a coming storm.

Behind him, something in the dust woke.

The horned individual standing beside his hut bowed low as Ajani returned, her smooth face splitting into a star-white grin. "It's such a blessing to be able to once again stand in the company of a hero."

Ajani flinched. "Nur. Please. We've spoken about this. I'm no hero. I'm barely more than—"

"Yes, yes. You're a sham, you're a disgrace to everything you stand for. A betrayer, who allowed hubris—" The djinni's smile remained luminous as she spoke.

"Mercy," said Ajani, setting the gazelle's corpse onto the ground. Blood streaked his white fur, a red gash crossing diagonally over his broad chest. Despite his melancholy, the Planeswalker could not help but smile. Nur was unrepentantly insolent: she seemed to hold few things sacred, and there were rumors she would even publicly tease the Abzan khan with no care for who was in earshot. This would be an issue if Nur wasn't so damned charming about it, something of which she seemed abundantly aware. "I cannot deal with one of your lectures today."

The djinni splayed a hand over her chest. She was wrapped in the lustrous colors of the Abzan, her emerald, gold-lined robes accented with purple. A bag hung from her right shoulder, the leather bulging with geometric shapes.

"Me?" said Nur, gesturing toward the leonin's hut as though it were her own. "Lecture? You slander me. I would never do such a thing. All I was going to say is each of us is a museum of our triumphs and failures. The existence of one doesn't negate the other."

Ajani growled then, a warning noise, his humor bleeding away.

"This can't be a courtesy call."

Unmoved by the leonin's ire, Nur said, "No, it isn't. The truth is that I was given a shameful amount of food and thought I would share it with you."

The djinni patted the bag at her side.

"Eating alone is, well, a terribly lonely thing, isn't it?" said Nur very softly.

"There are worse things to suffer," said Ajani in an even tone. It wasn't the first time that the djinni had tried to lure him from his isolation. By and large, the Abzan were respectful of Ajani's privacy. He had met with their khan when he first arrived on the plane, promising that he would assist at their borders in exchange for the privilege of being left to his own devices. The Abzan had said yes, of course. But as the months passed, as Ajani joined them on their hunts and their rescues and they learned of the pain the leonin carried, the clan began to have a change of heart. Delegates were soon sent to convince Ajani to allow himself help. Cynically, Ajani was sure it was for an entirely mercenary purpose. Why wouldn't they want a Planeswalker to throw in his lot with their people? When he turned the nineteenth ambassador away, Nur began appearing at his door.

Unfortunately for Ajani, he liked Nur.

"Indeed, there is," said the djinni, her attention falling on something behind the massive cat warrior's shoulder. "For one, you could be dead and furious and lost."

Ajani turned as she did. The air swirled with debris. There were faces moving in the sand-silted wind. Agonized faces, contorted with grief and rage and hate. They hated him, hated Nur, hated the living world, hated most of all the fact that they'd been left there, their Kin-Tree extinguished, their names forgotten; they were no more than a mass of untethered memories. The first time Ajani learned about the ancestral maelstroms, he'd thought them tragic. Now, he envied them a little.

"I've heard stories of when life was simpler. If your elders wanted to beset you with their grievances, they waited until there was a festival before swarming you. Now, they kick up a fuss wherever and whenever they feel like. Don't you think it's rather discourteous? Our dead, they can be so rude in their unlife." Nur said conversationally, beginning to walk toward the gathering spirits. "Apologies. It will not take more than a minute."

The djinni threw her arms open. Ajani, who'd learned to get out of the way when Nur was at work, turned his attention instead to the gazelle, pulling a knife from his pack to split the carcass in half. Every part would be used. From blood to bone, tendon to teeth, Ajani would find a use for it. He owed the animal that at least.

"Revered uncles, esteemed aunties, I understand you have issues—" If Nur's smile had been bright before, it was phosphorescent now. Her voice took on a certain melodiousness, a cadence like prayer. "—and I respect them. I understand what it is like to feel adrift. Lost. And you have every right to be in pain. But we did not forget you. We will not abandon you. Your tree will be found, and it will not be lost again. I promise you. Just please, I need a moment first."

Ajani could never tell what it was: actual magic, some innate gift for assuaging spirits, or the fact Nur was entirely sincere in her sympathy for those lost souls. For all her smarminess and her penchant for irreverence, the Wandering Warden (as she was known among the Abzan) cared furiously for her duties. Either way, Nur's work proved uncannily effective. The maelstrom grumbled a few more grievances before, satiated, it permitted itself to dissipate, leaving Nur to stand alone in its wake, bowed elegantly, a penitent expression worn on her face.

"I suspect they'll return before long, but we'll have time to indulge in breakfast first." Nur looked down at Ajani's butchery, mouth falling into a soft o of revelation before she reshaped it into a grin again. "Or perhaps, lunch. Come, my friend. Let me help you with that."

Ajani had to admit it. The spread that Nur had brought was phenomenal. Far better than the sparsely seasoned gazelle meat he roasted. There was rice fragrant with spices, warm stews, slow-cooked meats, flatbreads with which to sop up the bounty, and an array of side dishes for which Ajani had no name. Nur bullied him into trying all of it, still smiling in that lustrous way, as if he'd asked for this, for her, for this unearned kindness.

"How have you been keeping, Ajani?"

"Alive," said the leonin. On his part, he had roasted both the marrow and the meat from the gazelle, keeping the former in its bones and skewering the latter on sharp branches. "It's all one can ask for, really."

"To be alive and nothing else?" said Nur and gestured at the air with a half-eaten pastry. Gold flakes rained onto the bare ground. "You might as well be a plant then. No offense, but it sounds incredibly tedious."

"Tedium is safe," said Ajani, regretting his words immediately.

The djinni pounced like he'd held out a choice cut of meat.

"Safe—" said Nur, leaning forward. Gone was the playfulness in her voice and expression. In its place, an unsettling intensity, and Ajani recalled anew that there was a reason her irreverence was so well-tolerated. "—is not the same as happy. You can be safe in a locked vault while dying of a gut wound."

"And you think I'm dying then," said Ajani, arms folded. His hut was barren of everything but the essentials, namely storage for food and a panoply of weapons. The leonin kept nothing in the way of creature comforts, what few gifts—embroidered blankets and lace-trimmed pillows—provided by the Abzan carefully stored and packed in a corner; it was ridiculous of him, he knew, but Ajani didn't feel like he deserved use of them yet.

"Very much so. A slow excruciating death of the spirit. I don't know how long you Planeswalkers live, but I can picture you a century from now: hollow-eyed, a ghost in all ways save for the fact you are still made of skin and muscle."

"I suppose that would make me a revenant," said Ajani pettishly because it was impossible to spend any time in Nur's presence and not be affected by it.

Nur shrugged. "The Abzan can help, you know."

"I don't want help."

The djinni raised her hands. "You have made that amply clear. I'm just saying that the Abzan could be of help. After all, the clan possesses a rather unique relationship with the dead."

That was certainly one way of describing the Kin-Trees that the Abzan maintained. These plants were like nothing Ajani had ever seen: half living wood, half lambent golden spirit.

"In keeping them close, we have learned that there is no escaping the past, no martyring yourself to it. Only coming to terms with what has happened," Nur's face cracked again into a luminous smile. "Which can be a difficult process. But that is why we have a great many counselors in Arashin, living beautifully luxurious lives."

"Warden—"

"Just think about it, will you? That's all I ask. You're my friend, Ajani—"

Someone else had called him friend, too, had believed he was still her friend until he raised his axe against her. Ajani would never forget Jaya's face as she plummeted from the Mana Rig, not her grief, not the betrayal in her eyes.

Nur's voice pitched to a whisper, truly serious for the first time, remorseless in her pity. "—and I worry for you. This isn't living. This is just a death deferred."

"Or punishment," said Ajani, unable to meet his guest's eyes.

"And who decides when it has finally fit the crime?"

The two did not speak again for the rest of their meal, something for which Ajani was only slightly sorry.

Had Narset her way, she would have gone with one of the older dragons, someone who wouldn't be missed by the sky riders, but the adolescent female wouldn't hear it, trumpeting her keenness to participate in the upcoming adventure.

"It'd be an honor to serve in this quest, Waymaster," she declared breathlessly in the common tongue for what felt like the umpteenth time, tail slapping the floorboards. "I've always dreamed of this opportunity. If you permit me this privilege, I will—"

"Yes, yes," said Narset. "Fine. Just be quiet, please. I'd like to leave before the monastery takes notice."

And so Narset saddled the young dragon, slightly chagrined to have been outmaneuvered that way and aware that the other denizens of the rookery could have called the alarm on them but chose not to. She wondered with detached interest what they'd say if questioned by the other monks but dismissed the curiosity a moment later. Narset had left them extensive instructions and other helpful documentation. They'd be fine. At worst, it would be slightly awkward when Narset returned.

Elspeth drifted behind her without comment or cursory attempt at conversation, which Narset was glad for, having no aptitude at small talk, although she recognized the strangeness of the angel's behavior. She was increasingly convinced that Elspeth's ascension had taken as much from the woman as it had given, that to kindle her celestial power, they had to burn away those things that made her human once. Narset wondered if she noticed and if she cared.

The angel did not speak until the red foliage and jeweled lakes of the Jeskai territories gave way to blasted terrain.

"Is this the Crucible then?" A faint opalescence seemed to sheen the barren rock.

"That it is," said Narset's mount eagerly. "They say it was lush wilderness before the titanic battle—"

Narset shook her head. "That is pure embellishment. It was always like this."

"Spoilsport."

"Have you returned here since you confronted the dragonlords?" asked Elspeth.

Suddenly, Narset was at the battle again. It was becoming clear the rebel leaders were at an advantage. Their spirit dragons were fresh born into the world, bristling still with the power of the storm that had created them, whereas their adversaries had spent centuries mortal and complacent, convinced of their unassailability. Narset urged Shiko forward, the two of them transformed into a spearhead aimed for the throat of Tarkir's masters. She shut her eyes as Dromoka scorched the air with the light of her breath, felt Shiko twist upward and the incandescence die. "A little more," she told her mount. A little more and the dragonlords would break, she was sure.

"Too many times," said Narset. "The stories always end with how we drove them into the storm. It sounds so heroic. But I often wonder if the dragonlords went into hiding and are biding their time before returning to Tarkir. Or if they were unmade by the storm and in the process, infected the very essence of the plane with their resentment of us. It isn't as far-fetched as it sounds. If you look below—"

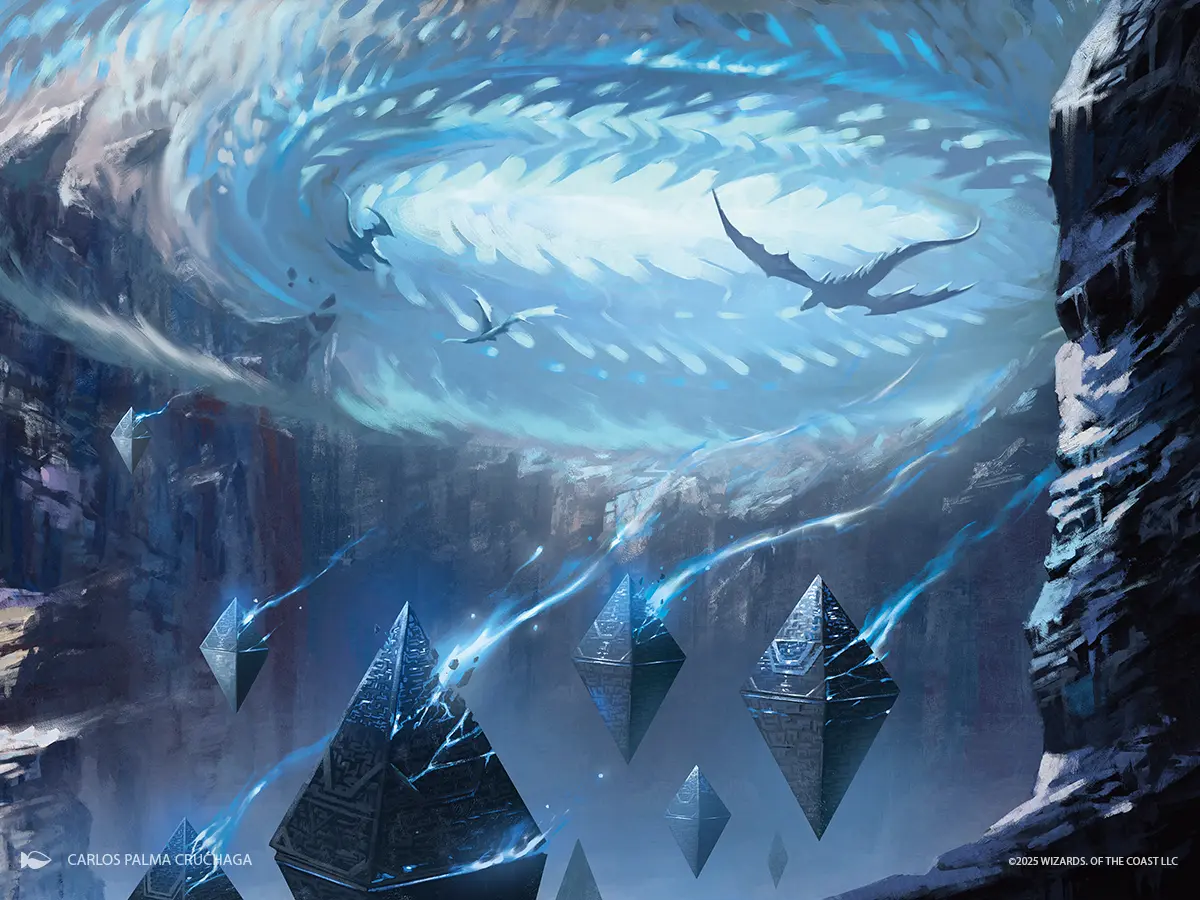

Narset gestured down toward where the land yawned into an enormous rift. In the vast chasm floated monoliths of varying sizes, each seamed with an eerie glow.

"Hedrons," said Elspeth, surprised. "I know Nahiri had built them on Zendikar to bind the Eldrazi. But what are they doing here? There was never any mention of her coming to Tarkir."

"Ugin taught her how to shape them. Or at least that is what I was told. And these, they hold a piece of his life force." Narset gave a light tug on her reins and the dragon, after a softly muttered, You could have just asked, arrowed down.

"If there are answers to what's going on here and elsewhere in the Multiverse," said Narset as they landed. "We'll find them in this place."

Those who seek will find a way.

Come to the temple where the truth awaits.

"Elspeth—"

"I heard it, too."

Above, a storm began to gather, serrated clouds giving way to the suggestion of eyes, bared teeth.

"The monastery will want to know another one is forming," said Narset lowly, a hand rested on her mount's throat. "I need you to go—"

"I'd rather have an adventure, if you don't mind."

Narset pressed her head into the dragon's white throat and, as she did, felt the dragon reciprocate in kind, muzzle touching her cheek.

"I know, but unity of mind—"

"Comes from forgoing personal wants in the interest of helping others. I am aware of this, Waymaster. I still don't want to, though."

"But will you?"

The dragon fluttered her wings like an irate goose, rearing up, acting every bit like a put-upon teenager though she was likely several decades older than Narset. She stared dolefully down at the two humanoids and sighed.

"Though it breaks my heart in half. Don't have too much fun without me."

"We won't." Narset reassured her, taking a long step back even as the dragon spiraled up into the sky, wondering throughout how much of it was because she was obedient to protocol and how much of it was because Narset feared putting the creature in harm's way.

When she was nothing but a glint of ivory above them, Elspeth asked,

"What now?"

"I—"

To the temple now before it is too late.

"There's something here," said Elspeth, her voice losing some of its affectless quality—though Narset couldn't quite identify what was leaking through.

"It feels like it's coming from the hedrons. What is it talking about? What temple? There aren't any temples here. I would know. I've been here so many times." Narset could feel it now: a tingling sensation, like an augur of lightning. The air seemed electrified, alive. Hungry. More than that, it felt impatient, and, for a dizzying moment, Narset was a child again and trying to decipher one of Ojutai's riddles even as her teacher waited and watched.

To the temple in the heart of storms.

"It is beautiful, isn't it?"

Narset jolted from her thoughts as a man emerged from seemingly nowhere, long black hair almost a cloak for his bare torso. His features were almost obscured by a beard grown overly long, but Narset would recognize his eyes anywhere.

"Sarkhan," said Narset softly. "It has been some time."

The man inclined his head. Fresh, vivid scars trailed over his muscular frame, and what armor he wore seemed more worn than Narset remembered. "Did you find the mammoth bones that you were looking for?"

"I did." Narset stared at him, feeling a prickle of ill-ease. Sarkhan must have had a purpose, a reason to be here. "What are you doing in the Crucible?"

His eyes glittered wet and hot and feverish as he stared up into the dragonstorm. The longing in his face embarrassed Narset with its intensity, and she found she had to avert her gaze.

"Looking for hope, I suppose," said Sarkhan, approaching further, only slowing when Elspeth drew her blade. His eyes narrowed. "You called the spirit dragons from such a storm, didn't you? A storm bigger and wilder than anything Tarkir had seen before. I've been tracking the weather since then, and it's—I think the plane yearns for an encore."

"What are you talking about?" asked Elspeth, her voice cold and flat as iron.

"From Tarkir came the dragons—"

"I don't think all dragons can trace their genealogy to—" began Narset, who sometimes could not help herself.

"And from Tarkir, more will emerge," said Sarkhan. Something about his eyes unsettled Narset: the sickly worship burning there made her think of a dying animal, dragging itself forward on want alone. "All of the Multiverse will become a realm of dragons."

"This will not happen so long as I live," said Elspeth.

"That can be fixed."

The fight, if it could even be called that, was over seconds after it began. Sarkhan Vol was a powerful man and an experienced soldier who had survived enough battles to know who he was as a fighter. But in his fevered state, stripped of power, he was nothing but another mortal, and Elspeth was both an archangel and Planeswalker. Sarkhan lunged, and Elspeth met his blade in an effortless parry, her saintly face devoid of emotion as steel rang out against steel.

"Enough."

Then she punched him.

It was a brutish, effective, and utterly unexpected move on Elspeth's part. Sarkhan sat heavily onto the ground, a palm over where Elspeth had struck him in the ribs with a mailed glove. He seemed utterly astonished to be taken out so handily, so much so that he did not look up even when the angel's winged shadow fell over him like judgment.

"Elspeth. Wait." Narset said. "He's—Sarkhan. Stop!"

Hard as the archangel had hit Sarkhan, it hadn't been enough. As the archangel spun to regard her friend, Sarkhan unfolded, snarling from the ground. The angle was perfect. With the archangel's wings, she would not be able to turn, not quickly enough, not before Sarkhan sank his blade through her ribs. Narset did not hesitate, fingers twinning in a complicated pattern before she spread her hands, mana flowing through her. Indigo light rippled through the air. The blast sent Sarkhan crashing to the ground ten feet away, panting and boneless and stunned.

"There's been enough death in Tarkir," she said after a drawn-out pause, hand set on Elspeth's wrist. "We don't need more."

Elspeth gazed at her with an expression like statuary, perfect and awful and cold. But then it softened and there was pity in her eyes as she stared down at Sarkhan, pity in the bend of her mouth as she sheathed her sword again.

"If you attack us again, I'll kill you."

How starved he was for a chance to once again be more than sniveling meat, soft-skinned. Breakable. Sarkhan clutched at his chest, feeling where the misplaced rib bobbed and bounced like the hand of a clock. He was humiliated. There'd been a time when he could have taken both his adversaries handily, but that time was lost along with his access to his true self. All Sarkhan possessed now was this form, this worm of a body: wingless, weak, worthless. His draconic form was still in reach, but transformation was so much harder these days. What once felt like freedom now felt like torture: his body no longer eagerly unraveled into metamorphosis; it screamed with pain. Everything hurt. And if his flesh had its way, he'd stay human forever, the thought of which frightened him terribly.

How desperate he was to have his past returned to him and this hateful present removed. Sarkhan swallowed against the pain and limped forward, long hair matted over his face. He walked for hours from the Crucible to the cold fields of Mardu territory. Sarkhan hadn't been ostracized, per se. Nothing stopped him from returning to his people save for his shame at being diminished, at becoming someone so weak. So, he made his hut here in the outskirts where no one might witness him in his senescence. Preoccupied with his agony, with memories of before and what came after, the joy he once possessed and this terrible loss, he did not notice the hooded figure standing in front of his shack until it spoke.

"Sarkhan Vol," the figure said in a booming voice. "I have heard such impossible things about you."

Sarkhan did not let his astonishment touch his face, only stared at the interloper with a cold look of distrust. "What do you want?"

"My name is Taigam," said the man, sloughing the hood from his face, "and, actually, I think I have something you want."