Founding of the City

Next week we'll be talking in more depth about the world of Ravnica as we get ready for Guilds of Ravnica previews. It will be our third trip to the plane of Ravnica. Before I start talking about that though, I thought it would be good to have a column looking back at our previous trips to the guild world. I will walk through how both Ravnica blocks got designed and fill you in on some of the behind-the-scenes stories I haven't shared before. Hopefully, that sounds like fun. (If, by the way, you want to read my original columns about their designs, here you go: Ravnica – Part 1, Part 2, and Part 3, and Return to Ravnica – Part 1, Part 2, and Part 3).

City Slicker

To start this story, we have to go back to the summer of 2004. For some context, there are a number of things that led up to this point:

In September of 2003, Champions of Kamigawa was handed off from design to development. The idea behind the design was that it would be the first top-down block where the mechanics would be designed to match the feel of a chosen world, in this case, one inspired by Japanese mythology. Interestingly, I was not on the Design team but rather the Development team, and I had many long conversations with Bill Rose—then head Magic designer in addition to being vice president of R&D—about how I felt the set had been built wrong and was causing us lots of developmental headaches.

In October 2003, we released Mirrodin. While the set was well received (it was for many, many years the best-selling Magic set of all time), it had a number of developmental issues and many degenerate cards started negatively impacting the tournament environment, especially Standard.

In December 2003, my then boss Randy Buehler convinced Bill that he was stretched too thin trying to be both Magic head designer and vice president of R&D. Randy sold Bill on the idea of letting me take the role of head designer. Bill okayed my promotion with one caveat: that I also be put in charge of the Creative team. All of our talks about Champions of Kamigawa had convinced him that there needed to be more integration between design and creative, and the way Bill thought we could assure that was by having the head designer also oversee the Creative team.

In February 2004, Darksteel came out and compounded our tournament problems. We ended up having to ban a number of cards in various formats, including Standard.

It was clear to me when I took over as head designer that Champions of Kamigawa block was headed down a bad path, but it had too much momentum for me to change a lot about it. In December 2003, Champions of Kamigawa was already out of design, Betrayers of Kamigawa was almost out of design, and Saviors of Kamigawa was partway through design. If I was going to make my mark (pun intended, as always), it wasn't going to happen until the next block (the sets codenamed "Control," "Alt," and "Delete").

I bring all of this up because my transition to head designer came at a very rocky time for Magic. I felt a lot of pressure to prove to everyone that my promotion was the right choice. My first whole block as head designer had to be amazing.

Color Me Impressed

Because so much was on the line, I decided that I wanted to lead design the first set of the new block. This would allow me to do something new that I felt Magic needed—block planning. Before Ravnica, here's how we made blocks: We'd design the first set. The second set then designed whatever it could in the space not covered by the first set. The third set then designed what it could for that not covered by the first two sets. Sometimes we'd hold back something for a later set (like enemy colored cards in Apocalypse), but that was the exception and not the rule. Under my new rein, I wanted us to think through the whole block at the very beginning, so that if we needed to save things for later we'd figure it out up front.

Going into the block, I knew only one thing about the set: it was going to have a multicolor theme. We had done Invasion block in 2000 to huge fanfare, and its success had convinced us to do another multicolor block as soon as we felt it was possible. After much discussion, we decided the appropriate amount of time was five years. Part of me was happy because I knew multicolor themes were very popular, but I also knew we would be designing in the shadow of Invasion, a very popular block. My goal was to capture as much as we could of what made multicolor fun while feeling as little like Invasion block as possible. I started the design of Ravnica with the mantra "Gold, but not Invasion."

What exactly though did "not Invasion" mean? I studied the block and came up with the following themes:

- Play as many colors as you can

- Ally colors are better than enemy colors (Ally colored cards outnumbered enemy cards three to one)

- Color matters (the block did a lot about mechanically caring what colors things were)

I decided to just take those and invert them:

- Play as few colors as you can

- Enemy colors are better than ally colors

- Color doesn't matter

Let me walk through how I thought about each one.

Play as Few Colors as You Can

Obviously, the fewest colors you can play would be one, but that would break with the only thing the block had to be—multicolor. That meant playing two colors. This led me to spend a bunch of time thinking about what exactly it meant to be two colors. It was this examination that led me to create hybrid mana. What if a card wasn't red and green but rather red or green? We had messed around with modal choices in effects on Magic cards, but never with mana costs. (The one exception being alternate costs where instead of paying the mana, you paid a different non-mana cost.) It was me trying to understand what exactly was the difference between "and" and "or" that led me to come up with hybrid mana.

Interestingly, when I first created hybrid mana, I was very excited as I felt I had uncovered something so basic that I couldn't believe we hadn't already done it. I was running around R&D showing it to anyone who would look at it—and everyone's response was very lackluster.

Me: I created something really cool. Take a look. (I show them the card I made.) It's not red and green. It's red or green.

Them: Okay. Why do we need this?

Me: It's a tool. You can do all sorts of things with it.

Them: Like what?

Me: Make a card that can go in a red deck or a green deck or a red-green deck.

Them: Is that something players have been asking to do?

Me: No.

Them: Then why do we need to do that?

Me: They haven't been asking because they didn't know we could do it.

Them: Maybe there's a reason for that.

Me: You're not remotely excited by this idea, are you?

Them: I have some work I need to get back to. Good luck with your weird mana.

As you'll see, it took a while for the rest of R&D to warm up to hybrid mana.

Enemy Colors Are Better than Ally Colors

How do you communicate that some colors are allies and some are enemies? One way is to show ally colors getting along mechanically and enemy colors hurting one another. Another way is to make it easier to play ally colors and harder to play enemy colors. Early Magic did some of both. Invasion block is a good example of the latter. Invasion had 350 cards. Planeshift and Apocalypse each had 143 cards. As Invasion and Planeshift were about ally colors and Apocalypse was about enemy colors, that meant ally-leaning sets were 493 cards to 143—or almost three and half times larger.

The new block could reverse this trend and make significantly more enemy colored cards, but the more I thought about this, the more it felt wrong. I'm a huge fan of the color pie, but I don't feel the need to communicate enemy colors through volume leads to the best gameplay. Let people play whatever color combinations they want. Maybe the best way to not be Invasion was to not treat the color pairs differently. Ravnica block would be unique by treating all ten two-color pairs the same.

Color Doesn't Matter

This was the one that took the longest to understand the message. Clearly, I could make "color mattering" not a big thing in the block, but I felt there was a more important message I could be picking up. What if the colors coming together was less about the mechanics of being two colors and more about the philosophy of being two colors? I'd spent a lot of time thinking about color identity and philosophy, so the idea of mixing and matching colors intrigued me.

Getting Creative

Thanks to Bill, I was now managing the Creative team. I really want to integrate them early in the design process, so once I got my rules ironed out, I talked to the team about what I felt the new world needed. Because I wanted a lot of back and forth between design and creative, I decided I'd start by giving them the bare bones of what I wanted.

The set was going to be about ten two-color pairs which would all be treated equally. I also mentioned I was interested in exploring what it meant philosophically to combine each of the two colors. That was it. That's all I told them as a jumping-off point.

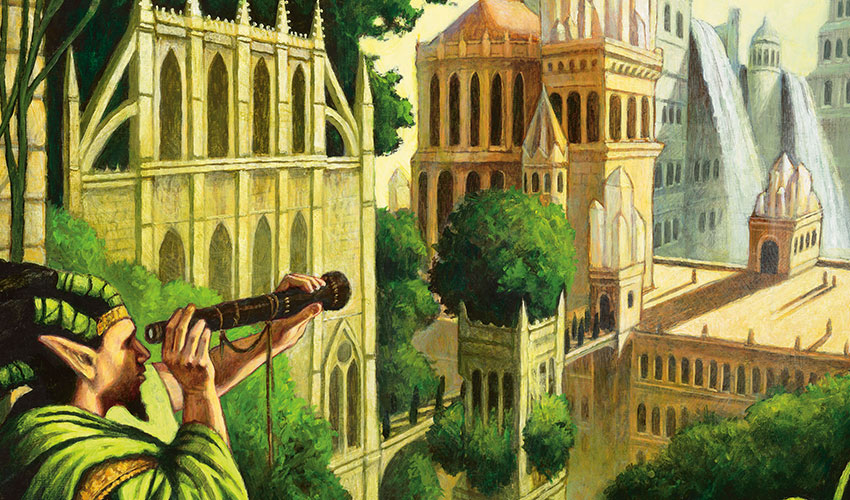

Brady Dommermuth, who was the most senior person on the Creative team, said they'd spend some time thinking about it. Months went by as they examined different ideas. Eventually, while working out one day, Brady Dommermuth came up with the idea of guilds, that each two-color pair would be its own faction, each with its own identity. With that idea in place, he locked onto the idea that it would be a city world, as that was the type of place where a structured system like the guilds would happen.

As I said, however, this idea wouldn't happen for a number of months.

A Hybrid Creation

My path trying to solve this problem led me to hybrid mana, so my design team (Mike Elliott, Aaron Forsythe, Tyler Bielman, Richard Garfield, and myself) made a whole bunch of hybrid designs. We then had a playtest. In the playtest were all ten two-color pairs on both traditional multicolor cards and hybrid cards, with a high as-fan of each. Now, many members of R&D are players who have been playing Magic a long time. Many are former pro players, some even in the Hall of Fame. The rule of thumb for R&D playtests is that R&D can handle a lot more than the average player. This is the only playtest in my time at Wizards where R&D members complained the set was too hard for them.

For example, normally when R&D breaks apart a Sealed Deck pool, they'll make thirteen piles: a creatures pile and a noncreatures pile for each color and artifacts, and a final pile for the lands. In this playtest, there had to be ten additional piles for each of the two-color traditional multicolor cards. And then, there had to be ten separate piles for each of the hybrid combinations. That's 33 piles of cards.

Most of members of R&D pride themselves on being able to figure out the optimal color combination for any Sealed pool, but the combinatorics were so large that even they started shortcutting the decision process. The message I got loud and clear from the playtest was "This is too much."

I walked out of this playtest in a bit of a panic. How could I capture the essence of what I wanted in a way that the audience could process? Was ten color pairs too much? Was I thinking about this all wrong? I was in desperate need of a new idea. That's when Brady asked if we could talk.

If You Guild It . . .

I remember listening to Brady pitch both the guild system and the city world. I was blown away. My response: "It's like a new way to look at the color pie, but with ten pieces instead of five."

Brady and I pulled in the rest of the Creative team, and we started talking about how we could represent each of the guilds. We talked through how to get each guild to be the embodiment of the two colors' philosophies intermingling. It only took one meeting for me to be confident that the Creative team could hit this out of the park.

I then went back to my Design team and explained that we were going to do the same thing mechanically with the guilds that the Creative team was doing with flavor. What did it mean for the two colors to team up? How would they expect to win? What synergies came about because those two colors shared their abilities? We also decided to give each guild their own mechanic, something to help solidify what they mechanically represented.

The guild system also solved my other problem. Ten two-color pairs was too much. By knocking the set down into ten component parts, we could solve the complexity issue by simply not putting every guild in every set. Each guild would get a chance to shine, but only in one set. The size of the sets pushed us toward a 4/3/3 breakdown. We explored other options, but 5/3/2 or 5/2/3 felt inelegant and made the set with only two guilds feel like less of a set. I knew we were onto something amazing, but I still had to convince the rest of R&D—and the rest of the company—to go along.

"Really?"

I started by getting my Design team on board. Well, most of them. Aaron, Tyler, and Richard liked the idea, but Mike was a bit skeptical. As Mike was the one other main Magic designer, his hesitance was problematic. Randy was my boss and the director of Magic R&D, so he was the next to convince. We had a good talk. Randy conceptually liked the idea, but was a little worried about execution. For instance, would the Draft format work? I told him I'd talk with Brian Schneider, the head developer at the time. Next was Bill. He thought the structure was interesting and said he shared a few of Randy's concerns about implementation.

While this was going on, news of what Ravnica was up to started to spread around R&D. The idea, without any context, sounded pretty strange. We were going to make a multicolor set and only four of the ten two-color pairs were going to be in it? The audience would never go for that. And it couldn't possibly work. The Draft, for example, seemed impossible to build.

Sensing a lot of the negative buzz, I was a bit apprehensive approaching Brian. I knew I could design the set, but if the Development team couldn't develop it, I'd have to try a new approach. I sat Brian down and walked him through what we were doing. I said, I know people were skeptical that it could be developed. Brian's response: "We can do it."

With Brian on board, I got the tentative go-ahead from Randy and Bill. There was some negativity to the idea from the rest of R&D, but as the senior management was on board, everyone agreed to give it a try. It ended up being one of the most popular Draft environments we'd ever built. Interestingly, I removed hybrid from the set before we went to the guild model, but in development, Brian came to me and said the set was a little low on innovation and asked if he could use hybrid (at the time I was using it in Time Spiral block) but just in a small amount (one cycle per rarity).

While the set was mostly smooth sailing from that point in R&D, the problems didn't end there.

Guilding Blocks

It's Brand's job to market new sets. They liked the idea of another multicolor set, as Invasion was popular, but they were worried that the idea of the guilds wouldn't come through. To assuage their concerns, we'd come up with the idea of watermarks that would be used to mark the various guilds as well as create a symbol we could use to identify them. Everything was going okay until we got a report back from one of our playtest groups.

At the time, one of the ways we would test sets is to send them to independent playtesting groups who would play the new cards and give us feedback. The playtest cards were the same ones we used at the time, stickers with no art stuck onto Magic cards of the appropriate color. One of the playtest teams who had played Ravnica came back with scathing reviews. They liked a lot of the individual cards, but they didn't understand what was going on. Why were only four color pairs represented?

These notes played into all the worries Brand had about the set. Brady and I went into damage control mode. We explained that these cards didn't have any art or watermarks and most of the names weren't final. The creative would have much of the burden of communicating the guilds, and we swore up and down that they were going to do a wonderful job of it. Brand said okay, but months later, when Brady and I were both on vacation, they added "City of Guilds" onto the name.

The set obviously went on to be wildly popular, and the guild flavor came through loud and clear.

"I'll Be Back"

After Ravnica block, we decided to space the multicolor blocks four years apart but wait for the second multicolor block to return to Ravnica. Return to Ravnica had none of the problems of Ravnica as the success of the initial block made everyone at Wizards confident about its return. If anything, it had the opposite problem. No one wanted to change anything. All the controversial things we had done became engrained as the way Ravnica sets were done.

The biggest change we did make started with Brian Tinsman pushing for a system where the final set of the block had all ten guilds in it. He proposed numerous systems, including one where the block stretched out over four sets. Once we realized we were limited to three sets, Brian pushed for a 6/4/10 model. He even mocked up a playtest using cards from the original Ravnica block. The problem was that a large set couldn't handle more than five guilds and a small one couldn't handle more than three.

Trying to think outside the box, I suggested making the winter set a large set and do 5/5/10. We'd never had a large winter set before, but I felt like it being a Ravnica set gave it the best chance of success. The other thing I liked about the second set being large was that it would allow each set to be drafted by itself. I always felt bad that there was no way to ever draft any of the guilds in Guildpact or Dissension alone. Allowing every guild to be drafted in its own large set would allow guild lovers the chance to draft just that guild. I believe Return to Ravnica and Gatecrash were a big influence in the modern "3-and-1 model" where each set is large and drafted by itself.

The final set of all ten guilds, Dragon's Maze, ended up being not quite as good as we'd hoped. Ironically, it ended up having a lot of the same problems as my initial Ravnica playtest all those years ago. Having ten guilds that all must be tracked and accounted for is just a little too taxing. That's why Guilds of Ravnica and Ravnica Allegiance don't have a corresponding Dragon's Maze set.

We also made the choice with Return to Ravnica to have ten new guild keywords. (Here's my Storm Scale article where I review all 20 guild mechanics and talk about what their chances are for a return.)

Interestingly, Return to Ravnica leaned very heavily on original Ravnica's design, so there's less to talk about in its design.

Third Time's the Charm

Hopefully, you enjoyed today's slightly different look at the designs of Ravnica and Return to Ravnica blocks. If you have any comments on this column or either of those blocks, you can share them with me through an email or any of my social media accounts (Twitter, Tumblr, Google+, and Instagram).

Join me next week as I talk about the designs of some famous cards from Ravnica and Return to Ravnica blocks.

Until then, may you find the guild that speaks most to you.

#565: Replies with Rachel 4

#565: Replies with Rachel 4

35:43

My eldest daughter, Rachel, is off to college, but before she left, I was able to get in one more podcast with her. We chose to continue with our mailbag series "Replies with Rachel," where she and I answer questions from all of you.

#566: Vidcon 2018

#566: Vidcon 2018

28:47

For the last three years, my daughter Rachel and I have attended Vidcon, a convention dedicated to YouTube video stars. This podcast is the story of this year's trip and all the things I learned from it.

- Episode 564 GP Las Vegas

- Episode 563 20 Lessons: It All Connects

- Episode 562 Vision, Set, Play Design Retrospective