Game On

Welcome to Magic: The Gathering® – Fallout® preview week. Annie Sardelis, lead designer of the Magic: The Gathering® – Fallout® Commander decks, has a dedicated article (coming soon) talking about how she and her team built them, so I thought I'd pull back a bit and talk about Universes Beyond design in a more general way. My article will cover how we adapt a video game into a Universes Beyond product. I'll also have a preview card for you before my article is done.

A Whole New Game

When looking at properties we want to adapt for a Universes Beyond product, they tend to fall into two categories: they are either story-based properties, meaning the audience knows them because of a story they've read and/or seen across various media (movies, television shows, books, etc.), or game-based properties, meaning the audience knows them because they've played the game. A game property doesn't exclusively need to be a video game, but often to garner the size necessary to have a large enough audience for a product, it usually has a video game component if it's not a video game outright. For today's article, let's assume we're adapting a video game into a Universes Beyond product. As it's preview week for Magic: The Gathering® – Fallout®, I will be using the Commander decks for my examples.

So, what challenges are there in designing a Universes Beyond product based on a video game?

Challenge #1 – Video games are more about experiences than plot.

In a story-based property, the audience all experiences the same story in the same order, so a lot of the design is about capturing story moments. In a video game, players don't all experience the same thing. The nature of a game is that you want to offer several options and allow the player to customize the way they play. This means that some aspects of the game will be very familiar to some fans and less familiar to others. There can be universal story moments, depending in how the game is structured, but the overall story is far less of a shared experience.

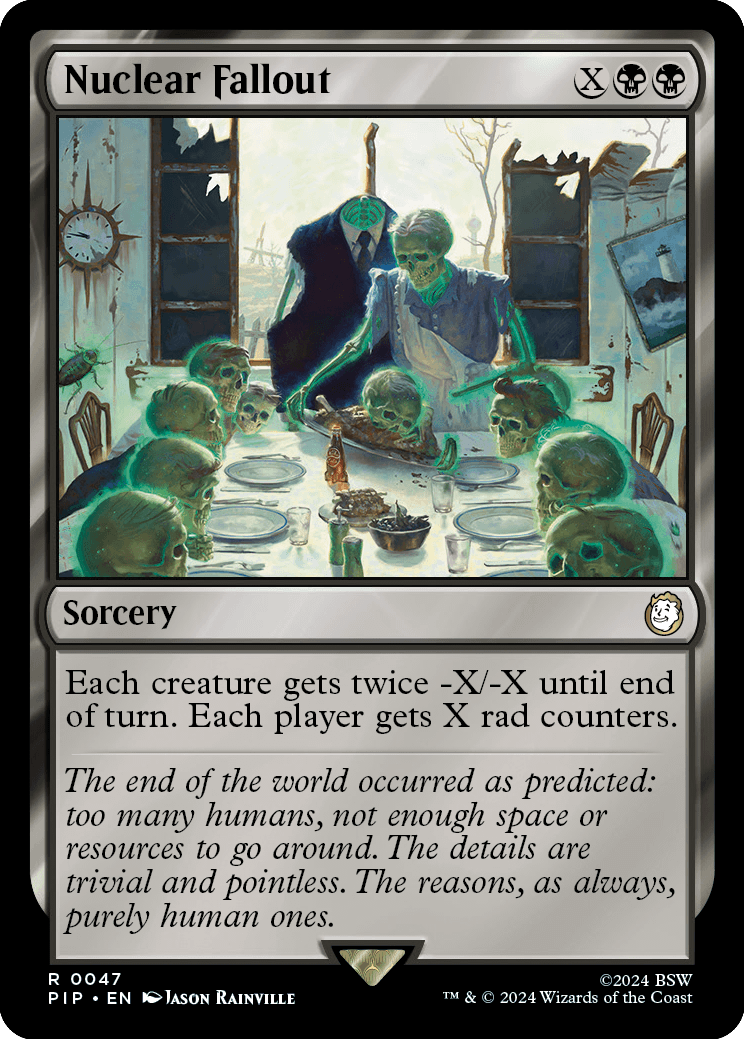

Let's take Fallout as our example. In the games, you are a post-apocalyptic survivor. What you choose to do in the game is up to you. Where you travel, what items you collect, what people you ally with—it's all up to you to decide. Universality isn't about what you do, as different players explore different paths, it's about the interface of the game. How do you, the player, choose to interact with the world. For instance, radiation is an important element of Fallout. In addition to a life total, you also have a radiation total. The game makes you very aware of it when you are interacting with radioactive material. It's universal. No matter how you play Fallout, it's something you must interact with. Finding these shared game interactions is core to capturing the feel of the game.

In addition to the interface, another important element we need to capture in the product is what, in game design terms, we refer to as "game loops." Basically, the goal of video game design is to find a series of fun activities that both challenge and reward the player. A good game loop will force the player to work on advancing something in an enjoyable way throughout the game, usually leading to some reward. It could be a skill upgrade, a useful item, and/or information that helps direct you toward completing a larger goal. This then leads you to the next activity, which generally involves a similar process. You might be in a new setting or fighting a new threat, but the basic process repeats itself. Usually, the game adds in new things for you to deal with using your new tools and/or upgrades and further rewards you for accomplishing them. It's an ever-evolving game loop (or sometimes game loops) that provides the crux of the game experience.

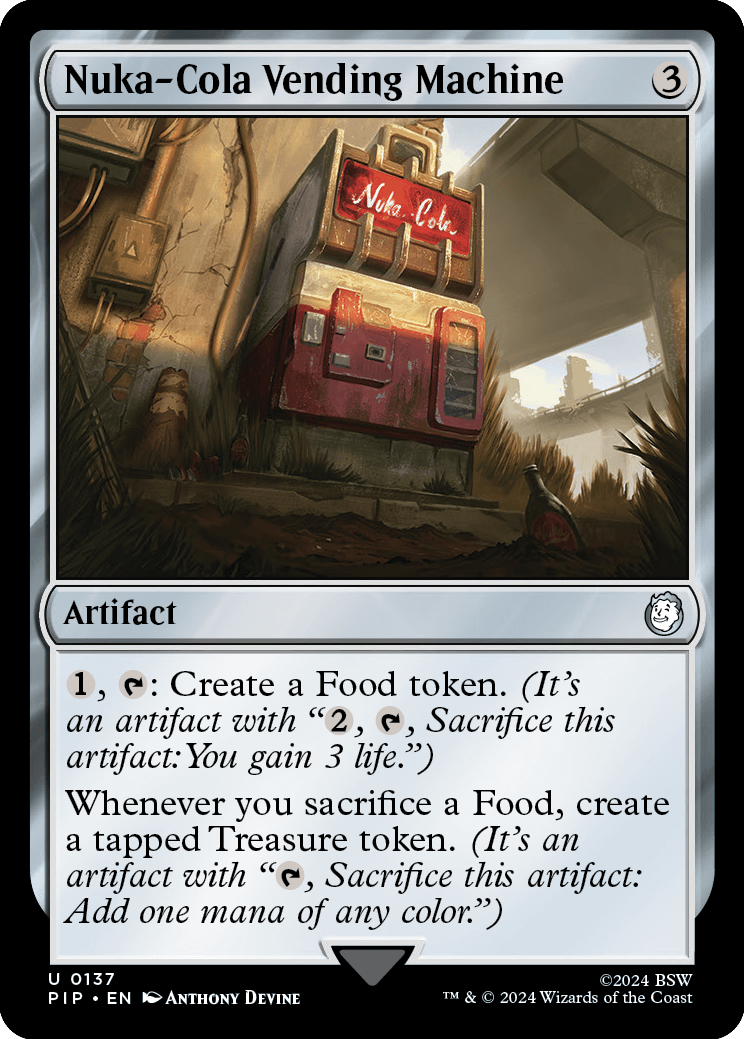

Fallout is what you'd call an open-world role-playing game. The game presents the world, and you, the player, get to explore it. Along the way, you get quests that give you objectives on the map. As you advance toward each objective, you're encouraged to explore. For instance, you hear from another survivor about an abandoned factory that's now overrun by feral ghouls. You go there, fight the ghouls, and kill them. You then get loot (i.e., items), either from the dead ghouls or the factory. You then equip or craft with those items (i.e., combine and/or use them to build better items), allowing you to explore further. The game loop is explore, combat, scavenge.

Much like the interface, the game design loops are one of the most universal things about the game. When we set out to capture the essence of Fallout, we had to capture these game loops.

The key difference between adapting a game-based property and a story-based property is that the game-based property is more about capturing the universal experience of playing the game than it is necessarily capturing specific moments in the game.

Challenge #2 – Selecting content is trickier.

To be a good candidate for a Universes Beyond product, a property needs to be relatively popular. For a video game, that often means it's a franchise, something in which many video games have been made. Fallout is an excellent example. The first Fallout game came out in 1997, and there have been numerous video games set in the Fallout world since then. While this is good in that it gives us a lot of material to design cards from, it creates the problem that there is more we could do than we have space to accommodate. When designing a Universes Beyond product based on a video game, the design team has to figure out what to prioritize.

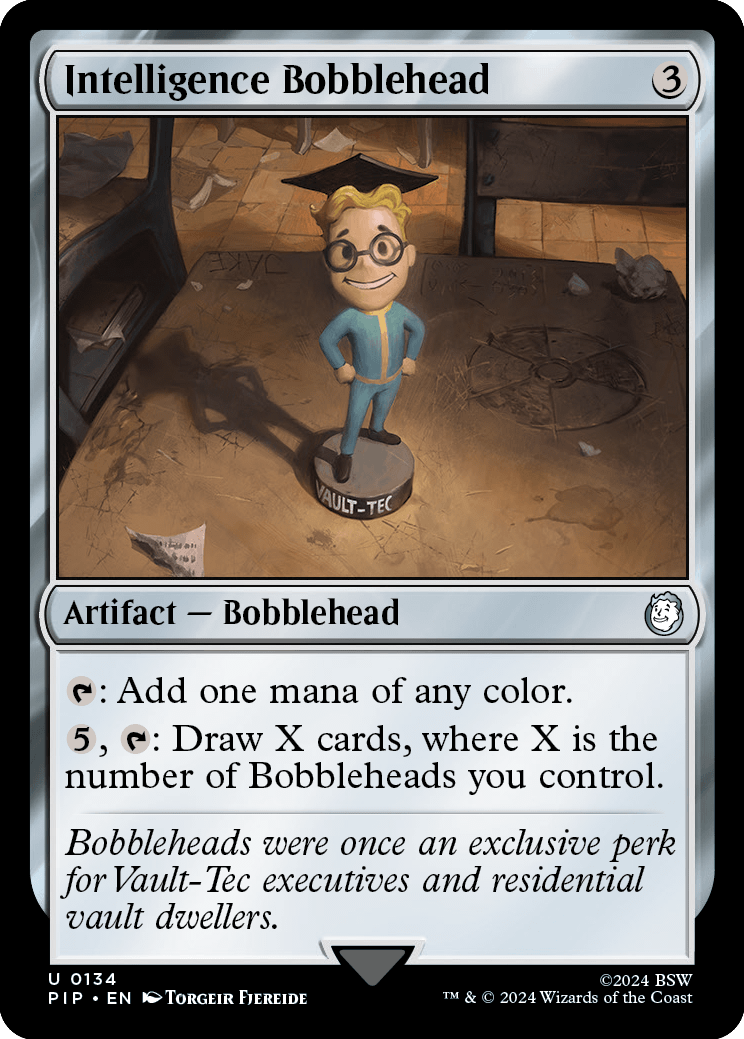

The first thing to focus on is familiarity. What components of the game would most players know? Are there things that exist across multiple versions of the game, maybe even every version? Are there things that are plentiful in the game that you see a lot? This is where the concept of as-fan and rarity come in. Low-rarity cards, by definition, represent the things that exist in volume in a world. When adapting a video game, you want to make sure your lower-rarity cards reflect the frequent elements of the game. For Fallout, that means things like radiation, ghouls, super-mutants, mutated animals, robots, bottlecaps, Bobbleheads, crafting, scavenging, raiders, and of course, Vault Boy (whose face is the expansion symbol of the set).

I should note that all the commons in the Magic: The Gathering® – Fallout® decks are reprints with new art, so any concept that wanted a specific top-down design had to be at least uncommon. Also, preconstructed decks, Commander or otherwise, tend to interact differently with as-fan than randomized boosters, so this challenge is a bit different between designing Commander decks and randomized boosters.

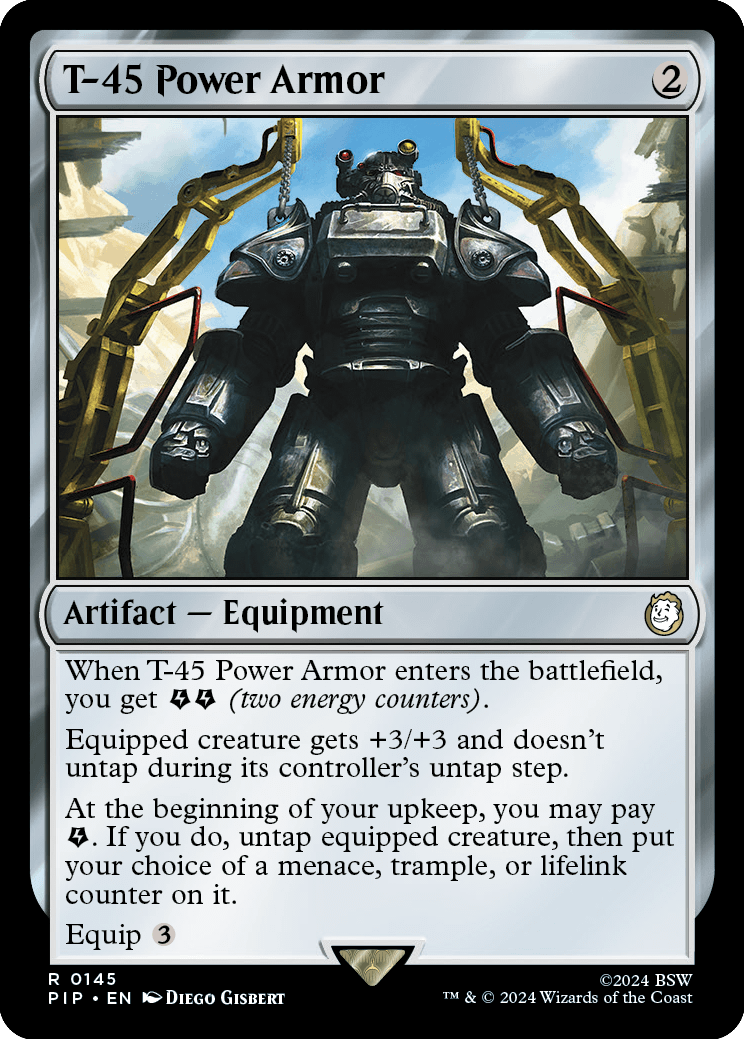

The second thing to focus on is popularity. This is why we have subject-matter experts (SMEs) on each design team and why we work so closely with the licensor, who is the expert on their property. We want to know what elements the fans of the property are most excited by. What must we include? What characters, items, and places must the product have? For Magic: The Gathering® – Fallout®, we knew we needed to draw from specific companions, equipment, and the Vaults.

The third thing is language. When people play the game, how do they talk about it? What vocabulary do they use? How do players of the game communicate with one another? Magic cards have a lot of words on them (names, types, subtypes, supertypes, rules text, flavor text, etc.), and those words can be used as a powerful tool to mimic the language of the video game.

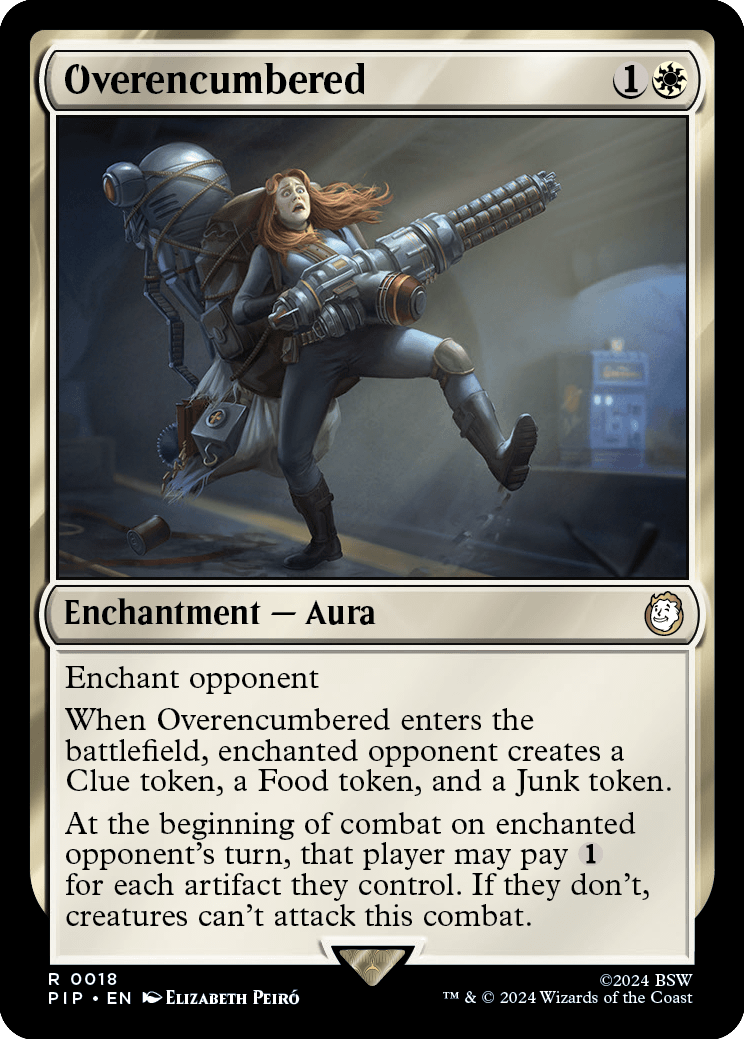

As an example, conditions can affect player characters, which can be a bonus or a limitation. These conditions have names that players are familiar with because they're used throughout the game series. For instance, Overencumbered is a condition players get when the weight of their inventory exceeds their maximum carry weight. It slows them down and causes other limitations. The design team liked the idea of being able to add status conditions to characters or players, so that you could use the vocabulary from the game as you played. Perks (a Fallout term for character bonuses) ended up being Auras (although all Auras are not perks), which allowed you to label specific characters or players as having the perk.

The fourth thing gets into our next category.

Challenge #3 – We must mimic game actions.

Capturing the feel of a video game requires having players do things in Magic that they would also do in the video game. As both are games, there's a big expectation that there's some overlap in how you play. Obviously, there are key differences between video games and card games, but because they're both games, there's a desire to replicate the general feel of the video game.

For example, Fallout has various resources that are important. Your health requires you to eat, and bottlecaps act as currency. The game had two different tokens, Food and Treasure, that can capture the feel of how those objects matter to the game. But items you scavenge are also an important resource, and Magic didn't have a great analog for that, so the design team created a new token type, Junk tokens, to represent this aspect of the game.

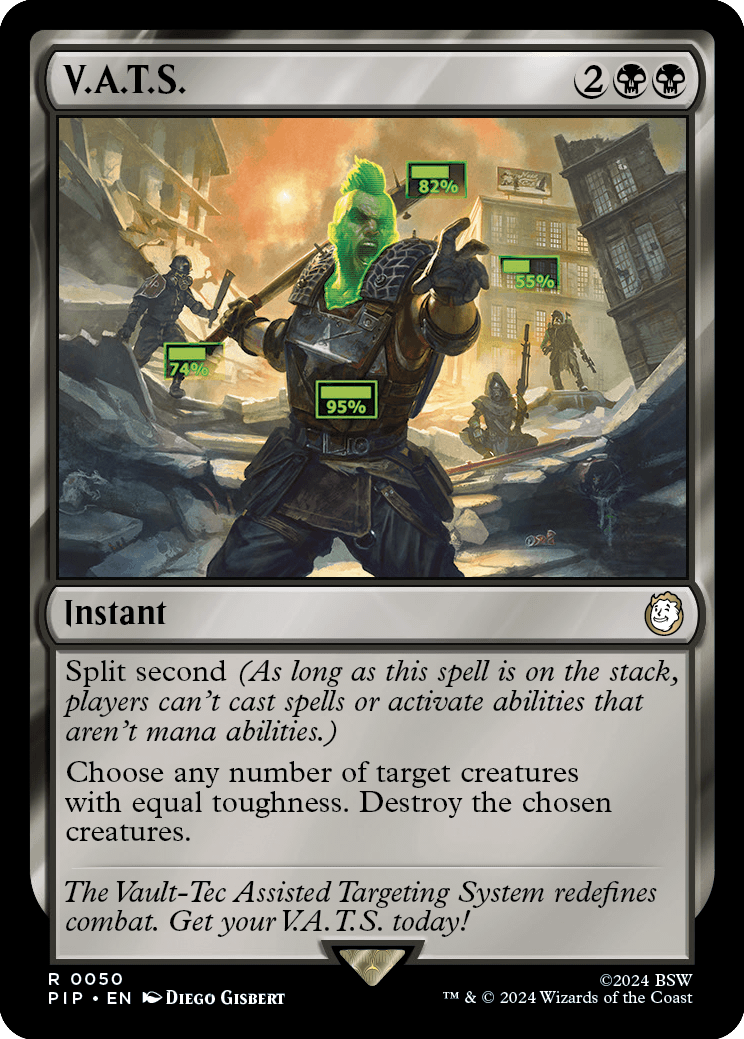

Sometimes, it's not even about replicating the action in the game as much as it is about capturing the feeling. For example, Annie and her design team were trying to figure out how to replicate V.A.T.S., which slows time in the game. Magic is turned based and not time based, so the concept of slowing time isn't something the game really has. They then realized that there was a way to do something that no one could respond to: the split second mechanic from the Time Spiral block. By putting it on a spell, split second allows you to create the feeling of doing something without interference, which captured the feel of slowing time.

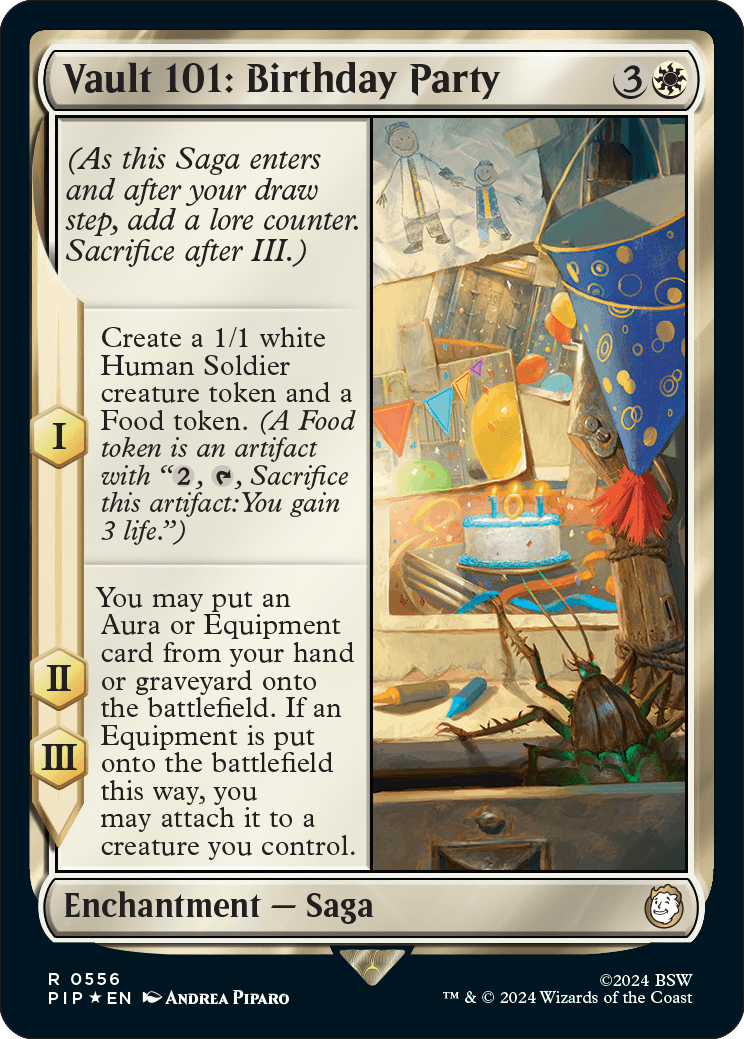

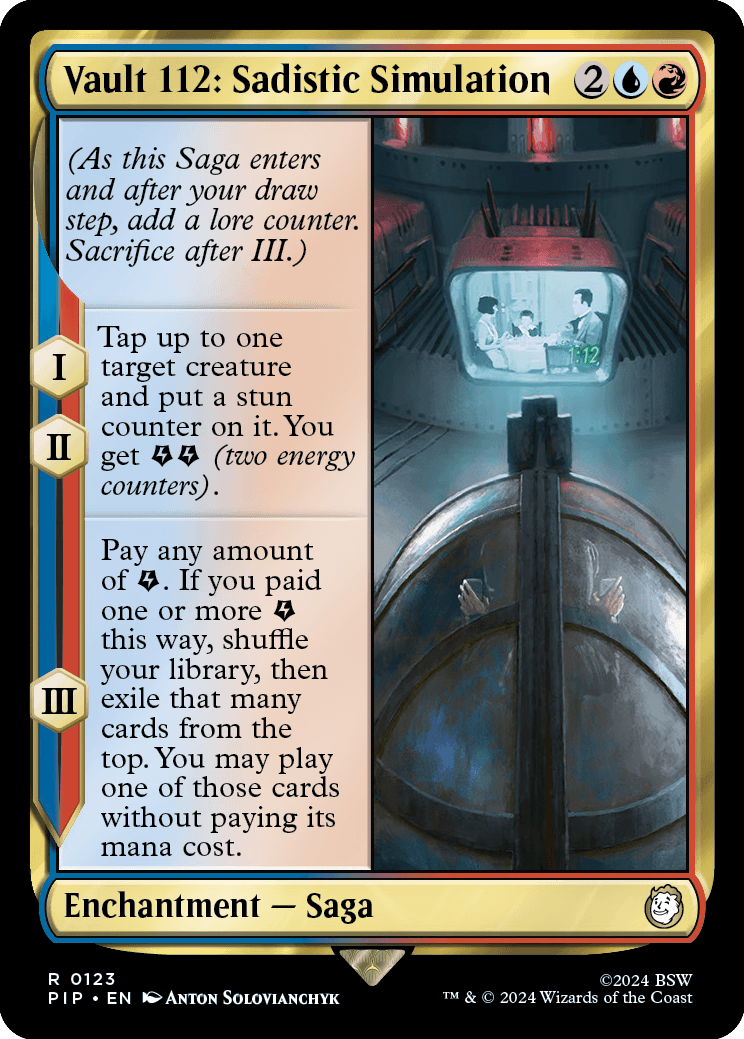

A big trap that can happen is when something feels like it has an obvious equivalent but the gameplay doesn't work out. A good example from Fallout is the Vaults. In a vacuum, Vaults seem like an ideal land. Lands represent places, and the Vaults are places. The problem is, lands come with a lot of restrictions, and that prevented the design team from getting them to feel the way they wanted. Eventually, when they stepped back, they realized that the Vaults were more about telling a story than being a location. Each Vault you visit shows what happened to the people in that Vault. Magic has a great way of telling stories, the Saga subtype. Using Sagas to represent Vaults did a much better job of bringing them to life and capturing the feel they create when you encounter them in Fallout.

A Universes Beyond design team has to find the right balance between making use of existing mechanics and creating new ones. Create too much new stuff, and it doesn't feel like Magic, but only sticking to known mechanics might not allow you to capture the feel of the video game properly.

Challenge #4 – Everything has to reference something.

I've spent a lot of time talking about how the design team has to replicate the video game through mechanics, but the opposite is also a concern. There are things that have to be in the design to make the game play well as a Magic game, and in a Universes Beyond product, everything has to be flavored as the property. The more overlap there is between the two games, usually the easier it is to find the right flavor for things such as spells, but there are always some Magic things that don't quite fit easily in the property.

In addition, sometimes the need of the game prevents making a new card. For example, each Magic: The Gathering® – Fallout® deck needed a few board sweepers for balanced play between the decks. Rather than creating several new sweepers, the design team had to find a mix of flavorful reprints and new designs. One of these reprints is Ruinous Ultimatum, which the team used to show Caesar conquering the region.

This challenge is a subtler one, because most of the audience's focus is on seeing all the components that they're excited to see represented, but any Universes Beyond product is still a Magic product and has to play well as one.

Challenge #5 – Video game players have a better understanding of the nuances of their game's environment.

Let's say you're designing two characters and you're trying to figure out the right power and toughness stats for each. In a story-based game, it often isn't clear which of the two would win in a fight. If the two don't fight in the story (with a clear outcome), it's all hypothetical. But in a video game, there's a much better chance that the characters are capable of fighting with each other because of the modular nature of video games, and game systems tend to want to break down characters into statistics. This means that the designers have a much tighter window to properly capture the game because the fans will know if they're a little bit off.

An example from Fallout is Agent Frank Horrigan. He's the endgame boss for Fallout 2, so there was a desire for him to be the strongest of the super-mutants. That meant the design team had to be conscious of how he appeared stacked against all the other super-mutants.

While there are a lot of challenges, there are a couple advantages one gets when designing a Universes Beyond product modeled after a video game.

Advantage #1 – Game players can handle more complexity.

Fans of a story-based property aren't necessarily game players. That means when you make a Universes Beyond game catered to them, it tends to want to be a little less complex. You want to make sure a fan discovering Magic through the product has a chance to learn it. The fans of a video game–based property (or to be fair, any game-based property) are gamers. They might have never played Magic before, but they're at least well versed in a lot of game concepts. That means they can handle more complexity in their Universes Beyond product. More complexity allows the designers some extra tools to help capture the feel of the game.

Advantage #2 – Video games tend to have more worldbuilding.

A story wants to have some worldbuilding, but usually it needs just enough to tell its story. A game, in contrast, is not trying to capture a singular storyline but rather an environment. In Fallout, you usually wander around the remains of a city. That means the creators of the game must map out both large and small portions of the city because some players, but not all, will visit them.

This need to map out environments matches how we approach worldbuilding in Magic. For instance, we create what we call the creature grid, that is, creatures of every size and color, because we know we will have cards that need the creative. A video game, likewise, must fill out its own creature grid so that there is a variety of things to encounter and often fight. So, when designing a Universes Beyond set using a video game property, a lot more work must be done to ensure that we have what we need to make a set.

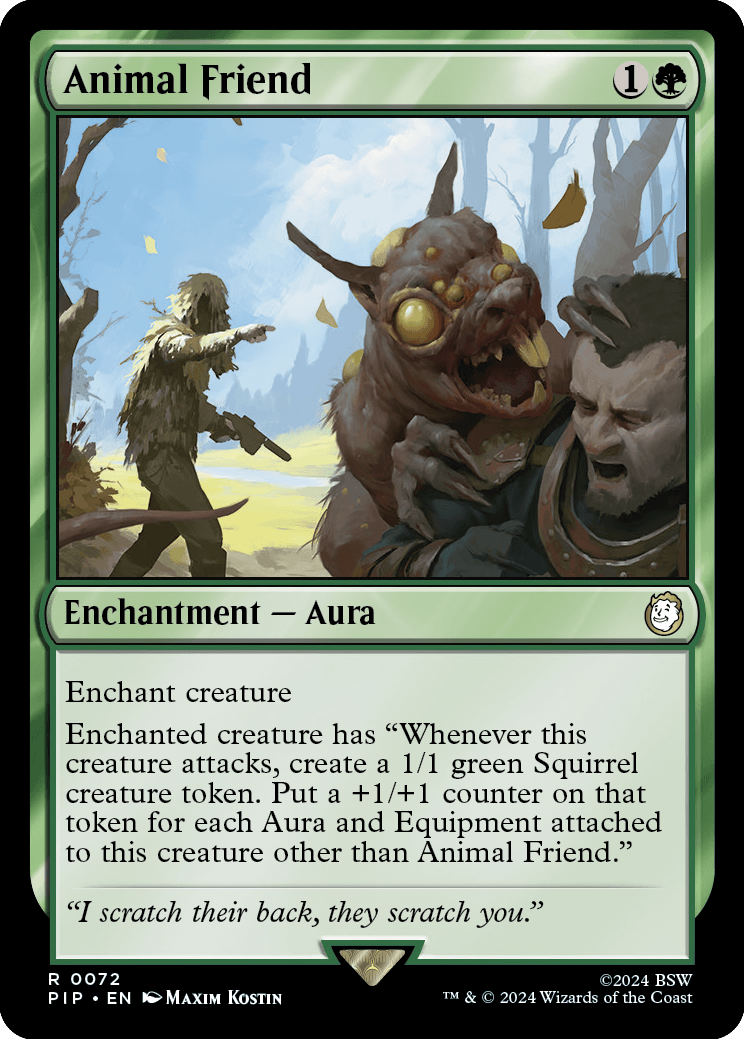

Who Couldn't Use a Good Friend?

Finally, before I wrap up for today, I have a card preview to show. Above, I talked about how mutated animals are a core part of the game and how perks are a game component that we wanted to capture on cards. My preview today shows off a different perk, one that allows you to bond with animals, often mutated ones.

-

Click here to meet the perk Animal Friend

-

Animal Friend

Animal Friend (Surge Foil)

Animal Friend (Extended Art)

Animal Friend (Surge Foil Extended Art)

Game Over

That's all the time I have for today. I hope this article gave you a better insight into the many challenges of making a video game into a Universes Beyond product. As always, I'm eager for your feedback, be it through email or any of my social media accounts (X [formerly Twitter], Tumblr, Instagram, and TikTok). Let me know your thoughts on today's article or on the Magic: The Gathering® – Fallout® Commander decks.

Join me next week for part two of my look back at the history of hybrid mana.

Until then, may you avoid being exposed to too much radiation, unless that's what you're after.