Getting Away with Murders at Karlov Manor, Part 2

Last week, I published my first preview article for Murders at Karlov Manor. I introduced the design teams, showed off some preview cards, and started telling the story of the set's design. I only got part-way through the design story, so I'm going to tell the rest today. I also have another cool preview card to show off. Also, we're doing something different with Murders of Karlov Manor. We've woven a series of puzzles throughout the products. I'll touch upon how that came about and how we made them.

On the Case

Last week, I talked about existing mechanics that inspired new, either via a return (investigate) or a tweaked return (disguise is a tweak of morph, and cloak is a tweak of manifest). This week, I want to talk about the mechanics that are playing in newer design space. Interestingly, these mechanics all stem from a new shift in how I've been thinking about design. (Note, I didn't design all the mechanics. As you will see, this shift set a certain direction in the goal for the set for all the designers.)

This story starts years before Magic even existed as a game. Before I was a game designer, my goal was to write for television. It was my dream to create television shows. To do that, you write what are called pilots, where you write the first episode of a show. It's designed to introduce the audience to your show. They meet the characters, learn the setting(s), and get a general sense of what the show is about. I wrote a bunch of pilots, but the one I was proudest of was called Tech Court. It was a science fiction courtroom drama. While working on it, I read a lot of books about writing for science fiction.

One point that really stuck with me was about the advancement of technology. The idea was that once you master a technology, you must make it feel as natural as possible. After you get past figuring out how to make the technology work, you want to figure out how to design it such that it's the most appealing and aesthetic to its user that it can be. This idea really helped me think about how to create a setting that existed decades in the future.

One of the cool things about the creative process is that you can take lessons you learned in one discipline and apply them to others. Yes, the lesson covered writing about the future, but I realized that it held a lesson about Magic design. You see, this is my 29th year designing Magic cards. One of my ongoing lessons has been about the importance of resonance. If our goal is to create a game that makes players happy, we should tap into things that already make the players happy. This is why we tackle different top-down themes and why we started doing Universes Beyond. There is great joy that comes from taking something you love and seeing it come to life through a Magic card design.

One day, I was thinking about resonance, and I asked myself, what's the next step, in game design technology, to making Magic cards feel more natural, more appealing, more aesthetic? This reminded me of the point about technology in science fiction. Was there a way to apply that to Magic design? After some thought, I realized the answer was language. As a writer, I have a great respect for words. They carry a lot of power and can shape how people think. One of the reasons, for example, I've been such a proponent of creating vocabulary for Magic design is so that R&D and the public have a means to talk about certain concepts.

Was there a way in design to prioritize harnessing the power of words? There was. What if when we work with resonance, we tag the words that we feel are most important and then use those words as jumping-off points to look for mechanical space. I bring this up with Murders at Karlov Manor because this was the first set where I had crystallized this idea. Here's how it worked. We spent time in exploratory design figuring out the words that best embodied the murder mystery genre, and then we spent time trying to find mechanics that matched the word that allowed us to write the phrases and sentences that felt the most resonant.

I should point out that in top-down design, there has always been a desire to match mechanics with flavor, and if we do our job correctly, it all looks seamless. The shift here was the use of the word as impetus for the mechanic. Think of it as designing a card to a name or to a piece of art. Both of those we've done before. In the past, we've designed to a concept but haven't designed to words as much. This time, I found the language I wanted on the card and worked backwards from that. I should also point out that I co-lead this design with Mark Gottlieb, and he, also a word person, was aboard on using card language as a jumping-off point of making mechanics such that they read as flavorfully as possible.

Let's start with an example. One of the important things about murder mysteries is that there is a crime, someone is murdered (not always necessarily murder, but a crime is committed). They are the victim. Then someone, usually a detective, must figure out who the culprit is. To do that, they make a list of suspects, people who potentially could be the culprit. The detective then collects evidence to eliminate suspects and zero in on the culprit. This act of figuring it out is referred to as a case.

Let's pull the resonant, top-down words out of the last paragraph:

- Victim

- Detective

- Culprit

- Suspect

- Evidence

- Case

These words are thematic of a murder mystery. Obviously, we can use these words in card titles and flavor text, but could we take it a step further? How do we get some of these words into rules text? Detective was the easiest. It's an occupation; it's something you do. Magic has a way to express this—class creature types. In Magic, if you're a Wizard or a Warrior, that appears on the card type line as a creature type. Cards can then mechanically care about those words. We decided early on that we wanted to make Detective a creature type, and then we would make typal card designs that cared about Detectives.

Victim and culprit were more challenging. Both usually apply to a single creature, and victim, at least in the murder mystery genre, usually means you're dead. Suspect, in contrast, was used in much greater volume. Most of the characters in a murder mystery, if they aren't the victim or detective, are suspects. This felt like it had a lot more potential to be mechanically relevant. Okay, let's say you could, in game, make a creature a suspect, what could that mean? That was a challenge given to the design team. What mechanic would allow us to write "suspect target creature" on a card?

Here are some parameters that Gottlieb listed when he posted about the assignment:

"Suspect" is a tag you can apply to a creature, and it has some sort of negative effect.

- The tentpoles for the set are cloak and Clues. Everything else revolves around them. This mechanic should probably not be a mana sink, a late-game upgrade, or something that has no effect on face-down cards.

- Based on our other mechanics, it's ideal if this goes into white (which doesn't have foul play or collect evidence) and not black (which has both), but if the new suspect mechanic is compelling enough, we could reconfigure the set to work it in.

- Ideally, even a single "suspect" effect would have a game impact.

Two quick notes: One, at this time in vision design, disguise was called cloak, and two, foul play was a mechanic that went on permanents and sorceries that allowed you to cast them as instants if a creature died this turn (sort of a tweak on morbid).

Here was a list of ideas that we talked through:

- A suspect deals 1 damage to its controller during their upkeep.

- It's harder for you to target your creatures that are suspects (costs more mana, perhaps).

- It's easier for you to target your opponent's creatures that are suspects (costs less mana, perhaps).

- If there are N or more suspect counters on a creature, it dies.

- Suspect doesn't inherently mean anything, but other cards care about it.

- We rename "cloak" to "suspect."

- Suspects can't attack or block. A creature is cleared after its controller draws three cards.

- Perhaps you put N suspect counters on a creature. It can't attack or block while it has any suspect counters on it, but whenever its controller draws a card, they remove a suspect counter.

- Suspects lose all evasion abilities; everything can block them.

- When a suspect dies, something bad happens to its controller (they lose life, for example).

- When a creature becomes a suspect, it gets turned face down.

- A suspect can't attack or block each turn unless you pay a tax/cost.

- A suspect loses its abilities and can't be turned face up.

- A suspect gets -2/-0 (and/or possibly other detrimental effects).

- Creatures ETB as suspects and you clear them through various individual means.

- Creatures have suspect counters on them (with some negative effect), and they can move them onto other creatures.

- Whenever a suspect is targeted, it gets -2/-2 until end of turn.

- Some kind of riot/unleash variant.

- Suspect = bounce to owner's hand when a Detective ETBs.

- A suspect ETBs untapped with a -1/-1 counter or ETBs tapped with a stun counter (controller's choice).

- Suspect counter = -1/-1 counter. -0/-1 counter?

- Suspect means "1: This creature gets -1/-1 until end of turn. Any player may activate this ability."

- You can discard a card to detain an opponent's suspect.

- More broadly, you can [pay a cost] to [lock down] a suspect.

- At the beginning of your combat step, you choose one suspect that can't block this turn.

- For a suspect to attack or block, its controller must give an opponent a Clue.

- Players may attack or block with only one suspect.

- Suspects can only attack (or block?) alone.

- Suspects can't block non-suspects.

- You can't attack or block with a suspect unless you tap another untapped creature you control.

- A suspect can't attack or block. It's cleared when it's targeted.

- A suspect can't attack or block. It's cleared when a creature an opponent controls dies.

The first attempt we tried with suspect was:

Target creature becomes a suspect. (It can't attack or block. As a sorcery, its controller may give each opponent a Clue to clear it.)

While it read well, it didn't play as well as we'd hoped. We talked about a "prime suspect" variant where it created an Aura that only went on one creature at a time (it was essentially an

We then decided that we wanted a variant where the cost of removing a creature as a suspect was higher than just giving an opponent a Clue, so we then tried a variant where it made a counter that went on a creature and kept it from attacking or blocking, but you could discard a card or sacrifice a Clue to remove the suspect counter. The cost of sacrificing a Clue would then change to paying 3 life.

In the end, we liked the idea that the ability had both a positive and negative element to it. Sometimes you'd make your opponent's creatures suspects, and sometimes you'd do it to your own creatures. Granting the creature menace felt like a flavor win. Of course, creatures would be hesitant to block a suspect alone. They might have committed murder. We then wanted it to pair itself with something that felt different but connected. Since menace is aggressive, we chose something defensive. A suspect can't block. That would make you want to attack with the creature, which advances the game rather than making you sit around trying to stall.

Once we tried this version of suspect (which happened late in vision design), we never looked back. It was flavorful and short, and it played well. The only thing we changed was a slight nuance in the language. Instead of making someone a suspect, you suspected them, and then they became a suspected creature.

Next up is collect evidence. (These all happened concurrently, so this order is not meant to be chronological.) The idea of collecting felt like acquiring a resource, so we looked at various resources you could acquire. That meant it couldn't be a resource you just start the game with, such as life. You had to acquire it during the game. There were basically three zones in which you could acquire. First was your hand. You could draw cards. Second was the battlefield. You could get some number of permanents, possibly a certain type or subtype of permanent, on the battlefield, or you could get a certain number of tokens on the battlefield, or possibly get some number of counters on a permanent. Third was the graveyard. You could either get some number of cards into the graveyard or use the graveyard cards as a resource. The last option wasn't a zone, but you, the player, could acquire counters.

The one that had the most resonance for us was the graveyard. A detective in a murder mystery cares about the victim, a dead character, and about the past, as they want to uncover what happened. Both dead things and the past are represented by the graveyard, so it felt right. Since you were "collecting" the evidence, we liked the idea that you were taking cards out of the graveyard. To play in slightly different space than other "graveyard as a resource" mechanics, we tapped into the idea that you could care about the total amount of mana value between the cards you exile. Originally, it was locked in at six, but as we played with the mechanic, we realized it would be valuable to have the collect evidence be a knob that we could adjust.

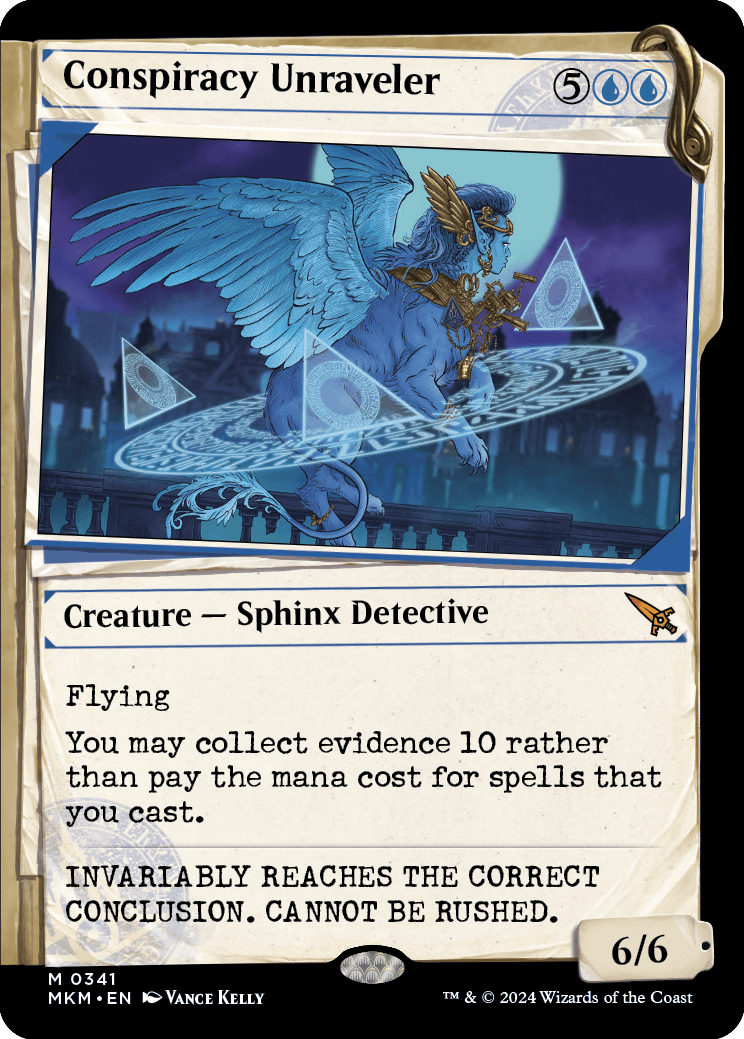

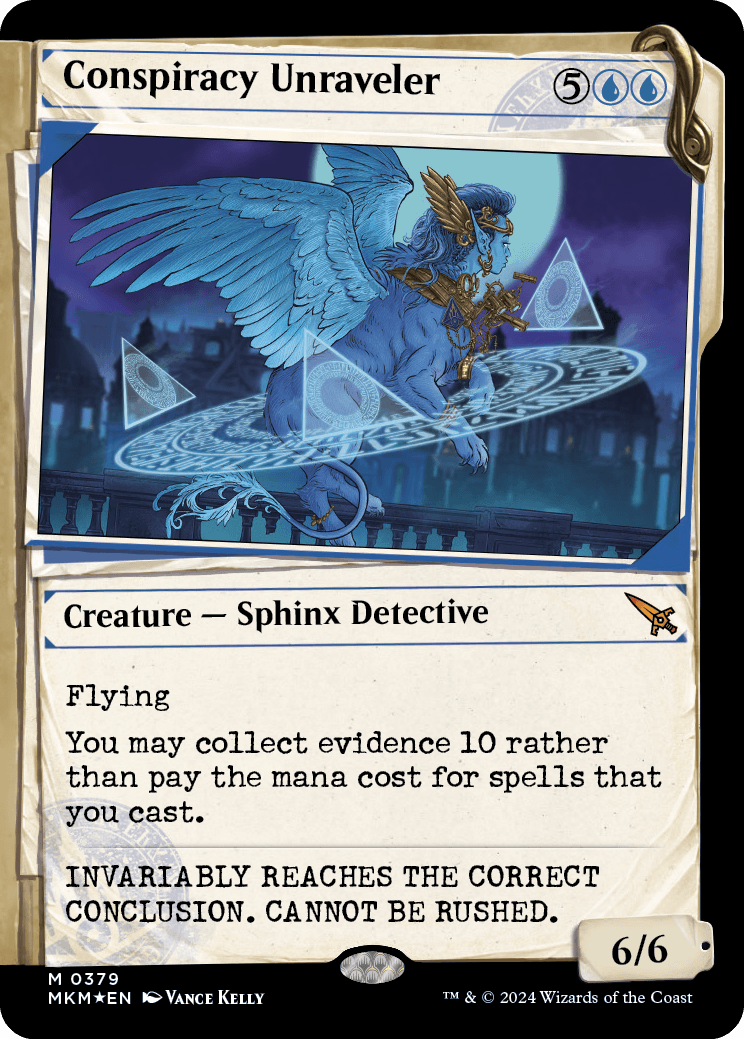

My preview card today is a collect evidence card. Click below to meet Conspiracy Unraveler.

-

Click here to meet Conspiracy Unraveler

-

Conspiracy Unraveler

Conspiracy Unraveler (Showcase Dossier)

Conspiracy Unraveler (Invisible Ink) As you can see, Conspiracy Unraveler demonstrates how you can do big effects with a larger collect evidence number. I'm excited to see what decks people build with this.

The last word we designed to was "case." The idea of having cards that were called "Case of the __________" seemed a perfect fit for flavor. It seemed obvious that Cases could be an enchantment subtype. Why enchantments? Because they're a thing, but a non-tangible thing, exactly the role enchantments fill as a permanent type. What exactly should a Case do, though?

1. It needed to be something you "solved."

Cases are essentially a task of the detective, and to capture the feel, we wanted you, the player, to have to achieve something.

2. It had to have a reward.

Making players jump through a hoop can be fun, but there must be a motivation to it. The player has to get something, otherwise they'll spend their time doing something else.

3. It had to have enough value to be worth putting in your deck.

This meant that it had to do something else after you solved it because playing a card that you conditionally might get an effect from wouldn't be enough value.

The general space of Cases is something we've been trying to do for a while. In original Zendikar, one of our versions of Quests was an enchantment that had a list of three things you had to do, along with a reward that you got for doing them. We tried that version of Quests again in Throne of Eldraine without any success. Streets of New Capenna tried a new enchantment subtype called Crimes that played in similar space, again without making it to print. Was there a different approach to try with Cases?

Here are several things we considered:

- Mystery 6 (Whenever you draw a card or turn a card face up, put an evidence counter on this card. If it has six or more evidence counters on it, it's solved.)

- Solve {4} (You may pay 4 and exile a creature card, an instant or sorcery card, and an artifact card from graveyards. Solve only as a sorcery.)

- (To collect evidence, exile a creature card, an instant or sorcery card, or an artifact or land card from your graveyard. Do each only once. Doing all three solves the Case.)

- (If the Case is unsolved, collect evidence by exiling a card from your graveyard with a card type you haven't collected yet. Once you've collected three cards, you've solved the Case.)

- Whenever you draw a card, put a solve counter on CARDNAME.

- [Activation]: [ability] Activate only if CARDNAME has three or more solve counters on it.

- Whenever you draw a card, put an evidence counter on CARDNAME. Then, if there are three or more evidence counters on CARDNAME …

- CARDNAME enters the battlefield with three solve counters on it. Whenever a creature dies or you sacrifice a Clue, remove a counter from CARDNAME.

- At the beginning of each upkeep, you may pay 1. If you do, [effect] and put a case counter on CARDNAME.

- When CARDNAME has three or more case counters on it …

- Whenever [condition], put a case counter on CARDNAME and [effect]. Then if CARDNAME has four or more case counters on it …

- Whenever a creature dies, put a case counter on CARDNAME.

- Remove three case counters from CARDNAME and sacrifice it: …

- As CARDNAME enters the battlefield, you may collect evidence. If you do, CARDNAME enters the battlefield with a solved counter on it.

- Solve N (It takes N hint counters to sacrifice this Case.)

- Whenever you draw a card, put a hint counter on CARDNAME. Then you may solve it.

- When you solve CARDNAME …

- (As this Case enters and whenever you cast your second non-Case spell in a turn, add a solve counter. Sacrifice after 3. [This was a Saga.])

As you can see, collect evidence and Cases were intermingled for a while. In the end, we decided that Cases worked best if they had three pieces. First, an "enters the battlefield" effect to make the card worth playing. Second, a hoop to jump through to allow the player the ability to solve the Case, but just one item. Our attempts with Quests and Crimes showed that multiple goals were too much. Third, a reward for when they do. Again, because words were so important, we liked weaving in the words "solve" and "solved."

Our focus on words didn't just stop on the main mechanics. The set, like any top-down set, is filled to the brim with names and card concepts that capture all the fun tropes of the murder mystery genre.

"The Game's Afoot"

The last piece of the puzzle was literally the puzzle itself. Last week, I talked about how Michael Ryan and I, years ago, envisioned doing a Magic set filled with a puzzle (when Starke was killed during the Weatherlight Saga). When we first decided to put Murders at Karlov Manor on the schedule, I was excited for us to bake a mystery inside. It was included as a component of the set from the moment the arc-planning team added it. The reason Mark Gottlieb was made co-lead designer for both vision design and set design is that he's a master puzzle builder. We knew if anyone could oversee a huge puzzle, it would be him.

Mark Gottlieb made a puzzle-building team with himself, Matt Tabak, Bella Guo, and me. Our first goal was to figure out what the puzzle was even about. The low-hanging fruit was for it to solve the actual murder(s) in the story, but it was important to the Creative team that the story itself could reveal who the murderer was, as it was a key part of the story. The puzzle ended up being a side mystery that Alquist Proft, our master detective, had to solve.

But how do we structure the puzzle? This is where Gottlieb's years of experience with puzzle making came in. A good puzzle quest needs a lot of individual puzzles that then link together to create one larger puzzle, meaning the answers of all the individual puzzles are themselves a puzzle, which then reveals the final answer.

We spent a lot of time brainstorming what type of puzzles we could do. The big restriction is that Magic is produced in many languages, and each puzzle had to be solvable in each language. For those of you who have never made a puzzle before, that's a big complication that restricts what types of puzzles you can do.

The team focused initially on what tools we had available to make puzzles. We could hide things in the main set of Murders at Karlov Manor, but we weren't just restricted to that. Any connected product (mostly) was fair game. In the end, we made twelve individual puzzles with a thirteenth larger puzzle that used the answers from the first twelve puzzles. If you're interested in doing the puzzles, you'll want to go to RavnicaDetectiveAgency.com. The first puzzle will be at Prerelease, and remaining puzzles will be introduced once a day on the puzzle website.

"The Mystery Begins"

That's all I have for today. I'm excited by the set we put together, as well as all the puzzles, and am eager for all of you to both play it and solve it. As always, I'd love any feedback on today's column, Murders at Karlov Manor, or any of the puzzles. Please reach me via email or any of my social media accounts (X [formerly Twitter], Tumblr, Instagram, and TikTok).

Join me next week as I share card-by-card design stories from Murders at Karlov Manor.

Until then, may you put your detective caps on.