Stone and Blood

Previous story: The Archmage of Goldnight

Six thousand years before the events of the Eldritch Moon story, three Planeswalkers collaborated to trap the monstrous Eldrazi on the world of Zendikar. Nahiri, a kor of Zendikar, stood vigil over the prisoners. Ugin, called the Spirit Dragon, and the vampire Sorin Markov agreed to return if their aid was needed. But the Eldrazi nearly escaped over a thousand years ago, and neither Sorin nor Ugin came. Sorin was Nahiri's friend, and his absence worried and puzzled her. After quelling the Eldrazi's escape attempts, Nahiri set out to find her friend. We know from Sorin's recollections that their meeting did not go well. But there are two sides to every story...

Reunion

One thousand years ago

Nahiri cast herself through the chaos of the Blind Eternities, the space between worlds. She'd slept for too long, in a cocoon of stone. Allowed certain things to drift beyond her awareness. She'd already corrected the most egregious case of neglect, reinforcing the wards that kept her prisoners secure and consigning their servants to oblivion. Her own world was safe, at least for the moment.

Now it was time to call on an old friend, and restore something less tangible.

It did not take long before Nahiri sensed his presence and aimed for it, warping the world around her until she could stand beside him. Their friendship was ancient now, a faded relic, but Sorin Markov had been her first ally, and Nahiri would know him anywhere.

She stood, then, on a high bluff overlooking a dark and choppy sea. She had never been here, but nothing about it surprised her. Innistrad and Sorin had shaped each other, and the world seemed to suit him—brooding and dangerous, almost purposefully unwelcome. And the moon—there was something odd about the moon that rose above the water, something that tugged at her senses.

Sorin had never brought her here, but he had spoken of it in wistful tones. Had hoped, she knew, to call upon her to defend it—as she had hoped to call upon him to defend Zendikar. Neither had gotten what they wanted, in the end.

Sorin was not here.

On the highest part of the bluff, where she had sensed his presence, stood instead a massive, rough-hewn chunk of silver, forty feet tall at least. It had faces, but they were irregular and uneven, as though an amateur lithomancer had pulled it out of the ground and not yet bothered to smooth it out to a finish.

But it was finished—unquestionably, to her senses, obviously the end result of tremendous effort rather than a work in progress. It was not polished because the polish did not matter to whatever it was this thing was supposed to be. Or do.

And this—this thing—was what she had sensed. Not Sorin. The Thing had spoken to her, through the tenuous medium of the Blind Eternities, of him.

There was nothing on the bluff but the wind and the silver monolith, save a stunted tree with red leaves. She left the tree to its business and circled the tremendous chunk of silver.

Sides. It had eight of them, or perhaps seven, depending on how generous one felt as to the nature of an edge. But faces they were, deliberately shaped, almost like...But there were no hedrons on Innistrad, and Sorin had neither means nor cause to make them.

And like a hedron, the Thing was more than its physical substance. She tested it with her lithomancy, taking a sounding of the pure metal and trying to get a sense of its inner structure.

Nothing. Nothing at all. She could sense the grain of the bedrock half a mile below her feet, feel the slow and steady heartbeat of continental plates dancing their slow, inexorable waltz. But she couldn't see into this sliver of silver. Couldn't so much as scratch it. Her power vanished into it, like an infinite well. Almost like...but no. No again. It was not a hedron. Not here.

She bent and peered beneath the Thing, half expecting to see that it was floating above the ground. But it was rooted at the bottom, by a comparatively thin stem of silver not much wider than Nahiri herself.

She stood and continued her slow circle of the Thing, trailing her fingertips along it in lieu of the deeper investigation she could not seem to make. She didn't know how much time she spent examining the silver monolith, but the moon was higher in the sky when a familiar voice spoke from behind her.

"You'll have to forgive my rudimentary attempt at shaping stone, young one."

She spun. Sorin!

White hair, black coat, those strange orange eyes. How terrible his aspect, how dire his gaze—and yet she could not keep herself from grinning.

"My friend!" she managed to say at last. "You're alive!"

He smiled back at her, walked toward her, and put his hand on her shoulder. From him, it qualified as elation.

"And why would I be otherwise?"

She reached up to cover his hand with hers. She was awake now, her body suffused with the warmth of life. His fingers were as cold and dead as ever.

"You never came," she said. "On Zendikar, when I activated the signal from the Eye of Ugin, you never responded. I feared that—"

Sorin withdrew his hand, frowning.

"The Eldrazi have broken free of their bonds?"

"They did, yes."

"Where is Ugin?" he asked.

"He didn't come either," she said, trying not to let bitterness reach her voice. "But I handled it. On my own. With all the strength I could muster, I managed to reseal the titans' prison."

It struck her, suddenly, that she was now far older than Sorin had been when they had met. In her memory he towered over her, her ancient mentor, a thousand years her senior. Now, what difference did a thousand years make? They were equals. At least.

"When the task was done, I came to find you. I had to know if you still lived. And here you are."

Here you are. Her joy at seeing him faded. She had been worried, so worried—that something had happened to him, or that he, like her, had sunk into a millennia-long malaise. She had come here to find him, to save him—but he was not, evidently, in need of saving.

"So, where were you?" she asked. "Sorin, why didn't you respond to the signal?"

"It never reached me," he said.

"How is that possible?"

"Hmm," he said. Just Hmmm, with little interest and no urgency whatsoever.

He reached past her and pressed a hand against the surface of the Thing.

"You have dedicated yourself to watch over the imprisoned Eldrazi, and it became clear to me that my plane was in dire need of its own protection, particularly in my absence. This Helvault is half of what I created to serve as such a protection."

Helvault. She shuddered. It was a vault. What could such a thing be meant to store?

"It's not inconceivable," he continued, sounding bored, "that your signal from the Eye was unable to break through the magic that protects this plane."

Sorin's own spellcraft had kept her from contacting him? She felt a sudden sense of vertigo, and picked her next words with care.

"Did you know at the time that that would happen?"

"It did not occur to me," he said. "Though I see now that it was a possibility."

Stone and sky!

Early in their association, before she understood what he was, and what she had now become, he had asked her if she wanted to learn to fight like him. She'd said yes—and then he'd tried to kill her.

Or so it had seemed to her at the time. She realized, not much later, that he'd been holding back, attacking her physically when he could have snuffed her with a thought. She held her ground, briefly, until his heavy two-handed sword had caught her upper arm in a glancing blow with a sickening crack, and pain overwhelmed her senses.

Well done, he said, standing over her. You lasted almost six breaths. Yours, of course. Now get up.

Get up? she cried. You broke my arm!

So fix it, he said. He wasn't even looking at her.

Fix it? Fix it? How in the hells—

Only then had he finally explained to her that she was no longer mortal. That her body was a convenience, a projection of her will.

You should have told me that to begin with, she said, holding back tears of anger.

Ah, he said, in that bored but benevolent voice. It did not occur to me.

He was using that voice now, talking down to her. But the girl he had mentored was long dead, buried in a tomb of stone. Only a Planeswalker remained. And a Planeswalker would not be condescended to.

"A possibility? You risked my plane, and more." She could not quite keep the hurt from her voice. "You abandoned me."

Sorin waved a pallid, dismissive hand.

"I was simply taking the appropriate precautions to protect my plane. I hardly think—"

Oh, enough. More than enough.

"We had an agreement, you and I," she said.

He could not deny that. Five thousand years previous, Nahiri had agreed, reluctantly, to trap the Eldrazi on her own world of Zendikar. And for their part, the other two Planeswalkers who had helped her had given her a way to contact them if the Eldrazi ever threatened to break free.

For five thousand years, Nahiri stood watch over their monstrous prisoners. She had locked herself away in stone, watched decades and centuries drift past like clouds over the sun. Then the Eldrazi had tested the bonds of their prison and loosed their hideous spawn upon a world already changed by their presence, in ways she did not fully understand. Nahiri had awoken, broken free of her self-imposed isolation, and sounded the alarm.

No one had come. Not the dragon Ugin, whom she had never fully trusted, whose motives and origins were enigmas. And not Sorin—her mentor. Her friend.

She had dealt with the crisis on her own, at great cost to her world, far more than it would have cost had her allies honored their agreement. She still hadn't surveyed the full extent of the damage the Eldrazi had done to her world and its people before she had quelled their efforts. But she had done it, and when it was done she had gone to look for him, fearing for his existence.

And found that he had done worse than ignore her cry for help. He had blocked it out, to protect his own world from outside influence.

He turned his back to her.

"Don't dismiss this," she said. "I was willing to jeopardize my home by luring the Eldrazi to it. I promised to chain myself to Zendikar to watch over them as their warden. I spent millennia with those monsters. Do you know what that's like? All you had to do was come when I needed you."

The ground began to shake, the bedrock below them vibrating in sympathy with her mounting rage. Of all the stone and metal nearby, only the silver Helvault seemed beyond her reach.

"Don't presume to own my actions, young one. I am obligated to nothing. I owe you nothing! When your Planeswalker spark first ignited, it was I who discovered you. I could have ended you there, but I spared you."

He turned back to her, orange eyes full of malice, face inches from hers.

"I took you under my wing, and molded you into what you are," he said. "If you find it necessary to pester someone, go find Ugin. I have no patience for it."

No patience. No patience. Pain gave way to anger in a white-hot instant.

For five thousand years, Nahiri had kept watch over the Eldrazi—not just for her plane, but for every plane. For Innistrad. And once, once, in five thousand years, she had called on him to do nothing more than make good on a simple promise—a self-serving promise, one that he'd only made because it would keep his own world safe—and he had not. Just...not.

Her own patience was at an end, spent in endless vigil over the Eldrazi. She was done—done waiting, done pleading, and most of all done being treated like a child. If Sorin needed proof that she was no longer his student, she would have to provide it.

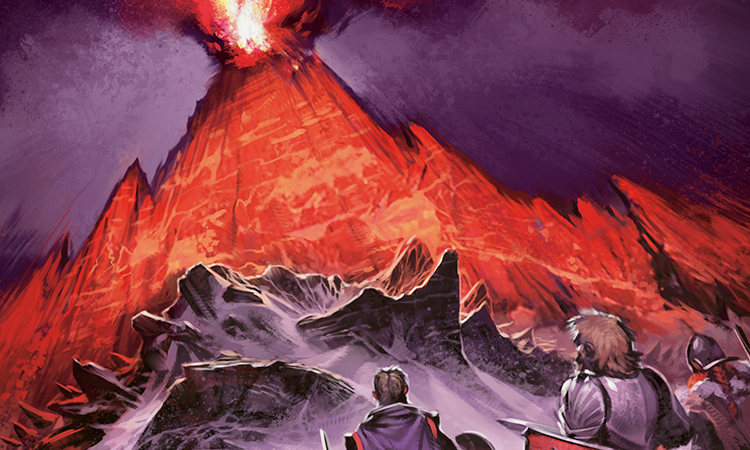

She called forth a column of rock from the depths beneath them—granite, old and strong. The earth heaved, and Sorin struggled to keep his feet. The stone column burst from the ground beneath her, carrying her high above him.

"I'm not going anywhere."

She pulled more rocks from the ground around her, sharpened into darts, swirling around the two Planeswalkers.

Sorin drew his sword.

"I never threatened you," he said, looking up at her. "Not once. If we are to be enemies, child, the blame falls solely at your own feet."

"I'm not a child," she said. "Whatever we were, surely you can see we're equals now."

There was a moment's hesitation—a hint of fear in those orange eyes, perhaps? A second spent weighing the possibility that she might be right, and his pride was in need of sharp correction?

"All I see is a tantrum," he said. "If you came to meet an equal, you should have come under truce, following the protocols for parley with a fellow Planeswalker."

"I came to meet a friend," said Nahiri.

"Then I see no grounds for complaint," said Sorin. "Friends deliver hard truths...do they not?"

Long ago, a foolish girl had called this wretched creature friend. As the last vestige of that youthfully sentimentality boiled away, Nahiri struck.

She hurtled down toward Sorin astride a fist of rock. She had no sword. She had no need of one. The ground itself was her weapon.

Sorin released a blast of death magic that caught her full in the chest, knocking her back. The stone column lurched backward, to stay under her feet.

Sorin vaulted off the broken ground and leapt straight toward her, teeth bared, sword glinting in the light of that strange, looming moon. She jumped from the column and landed on the ground in a crouch. Sorin hit the stone column feet first, ready to spring off of it and attack her again—but the stone column simply swallowed him.

She stood, fists clenched, squeezing Sorin in the stone.

Cracks appeared, first one, then several, shining with light from the vampire's magic. The column flew apart in a spray of light and stone as Sorin forced his way out. He dropped gracefully to the ground.

But he looked pained.

"I don't want your enmity," said Nahiri. "All I ever wanted was your help, Sorin. You made a promise. Come with me."

"Not now," said Sorin, with infuriating calm. "Later, perhaps. This is a critical time—"

"A critical time!" snapped Nahiri. "The Eldrazi almost escaped. You're thinking in terms of eons, but for all I know the Eldrazi are loose now. All that we worked for will be lost, your own plane will be in danger—don't you care about that?"

It hit her, then. The imprisonment of the Eldrazi had become her life's work, a constant effort that had kept her bound to her plane for almost her entire existence. But for him it had been an eyeblink—forty years of mild effort, five thousand years ago, in exchange for millennia of peace of mind. And now, with his new countermeasures, perhaps Innistrad wasn't in danger. Perhaps Nahiri and Zendikar and a hundred million carefully placed hedrons had served their purpose, in the mind of Sorin Markov.

She snarled and sent a storm of stone darts flying at him, each the size of her forearm and sharpened to a wicked point.

Sorin blasted a few of the shards to dust before they reached him, sent several more spinning away with a sweep of his sword, and grunted as three more pierced his body.

His eyes flared white, too bright, and a great weight settled on Nahiri's shoulders, forcing her to her knees. Everything was so bright—

She looked up.

The moon. He had called down a beam of moonlight, heavy as a boulder but with no substance whatsoever, to bind her. And finally, surrounded by its light, breathing in the scent of it, she understood what was so strange about Innistrad's moon.

It was made of silver. Like the Helvault.

Sorin pulled the stone darts from his body one by one, the wounds closing bloodlessly. He stalked toward her. But his footsteps were uncertain, his sword drooping. Had he become so decrepit?

Still, his magic was strong. The light bound not only her body, but her magic. As long as it held, she was powerless to affect anything outside its radius.

"Go home, Nahiri," he said wearily. "End this farce, and I will allow you—"

She dug her hands into the soil, extending her will not out, but down, and dove into the earth itself.

She sank down into a womb of stone, and for a moment she left behind her anger and Sorin's damnable arrogance and that strange and unyielding chunk of silver whose purpose she still couldn't grasp. There was only her and the stone, cut off from everything save the slow and steady heartbeat of the world, like it had been for five thousand years.

She could planeswalk away, return to Zendikar and to isolation. She did not, in fact, need Sorin's help. Not anymore. But leaving things unresolved here would be dangerous beyond measure, inviting retaliation. She really would have made an enemy, then. And she wouldn't leave while there was still a chance of preventing that.

Sorin's restless footfalls echoed above her, stalking toward the Helvault.

She shaped the stone beneath her into another pillar, thinned the rock above her to the consistency of water, and burst forth from the ground once more. Sorin had dispelled the beam of moonlight, and now had his back to the Helvault for some measure of protection.

She rose on her granite pillar, towering above him, pulling a swarm of stones from the ground and arraying them around her.

She didn't want to kill him. She didn't really want to hurt him. What she wanted was for things to be right between them, the way they had been. But for that to happen, she would have to earn his respect. And to do that, she would have to beat him.

He was leaning on his sword, now. If they agreed to treat one another as equals, it seemed she would be doing him a favor.

It wasn't right. He was too weak, weaker than he had been when she was young. She thought of how the Helvault had radiated his essence, and wondered just how much of himself he had poured into it.

She sent her pillar of stone gliding forward toward him. As she slid past one of the floating stones around her, she reached into it. It instantly heated, became molten, as the metals inside it coalesced in answer to her will.

She pulled a fully formed stoneforged sword out of the rock and kept advancing, until Sorin stood beneath her, gazing up at the sword's white-hot point.

"Sorin, you will fulfill your promise. You will return with me to Zendikar. You will help me check our containment measures, and ensure that the Eldrazi are secure. Only then can you slink away."

Sorin spat.

Then everything went bright again, brighter than the moon, and a shape came screaming out of the heavens. She glimpsed feathered wings and a shining spear before the figure slammed into her, knocking her off her pedestal. They tumbled together and slammed into the ground, where they carved a deep furrow in the earth. Nahiri's array of stones tumbled to the ground, her concentration shattered.

At last, lying on her back. Nahiri got a look at her attacker.

She was an angel, larger than life, with white hair and white skin and dark, expressionless eyes. Nahiri was being attacked by an angel.

Nahiri had met angels, on Zendikar. They were aloof, and could be fearsome, but they were protectors, creatures of justice and of good. And none of them that she'd ever met were stupid enough to attack a Planeswalker.

Before Nahiri could speak, before she could even fully process what was happening, the angel raised her spear. Its points shone like twin suns, blinding her.

She sank down once more into stone, felt the spear's points dig into the earth where she'd been lying.

No time for repose, this time. She burst from the ground in a spray of shrapnel, sword still in hand, and as the angel shielded herself from the blast of rock, Nahiri attacked. She swung the sword, which still glowed with the heat of its forging.

The angel raised her spear to deflect, just in time, and Nahiri attacked again, and again, and again, forcing the angel backward. She felt a dim sense of wrongness, fighting an angel. But no—the angel had attacked her, unprovoked. And why? To protect Sorin? She could scarcely entertain the thought.

The angel vaulted into the air—but not to retreat. She sprang forward, to get above Nahiri, to attack again. Nahiri rose again on a stone pillar, to force the angel either to flee or to return to the earth.

The angel settled again, but stood her ground. Nahiri kept up her assault. The angel was powerful, no question. But she was no Planeswalker. Nahiri struck again—

—and her sword stopped dead on Sorin's, thrust between her and the angel.

"Enough!" he panted. "Enough."

She stared past him, at the angel with the jet-black eyes. There was something familiar about the angel, something unsettling, though Nahiri was quite certain she'd never seen her before.

"What is this, Sorin? How did you bring an angel under your thrall? Who is she?"

"The other half," he replied.

His hand whipped out, lightning-fast, and closed around Nahiri's sword. His skin hissed and sizzled, but he didn't seem to notice. Nahiri's fingers were numb, her mind reeling. She still didn't understand. He lifted the point of his own sword to her throat, wrenched her blade out of her hands, tossed it away.

The angel landed softly behind Sorin, but he held up one hand, and she waited. An angel waited, for him!

"For what it's worth," said Sorin, "I never wanted this, young one."

Then Sorin raised his sword, lashed out with a beam of tarnished light, and pushed.

Nahiri flew backward and slammed against the silver surface of the Helvault. It was no longer hard and cold, but yielding. Welcoming. Pulling.

Strands of eager silver closed around her body, drawing her in. Shards of rock whirled through the air, the bedrock beneath their feet shifted at her rage, but the Helvault itself did not care.

"Damn you!" she screamed. "I trusted you!"

He loomed over her, now, the angel's wings spread behind him, and he spoke one last time before molten silver flooded her ears. He sounded almost sad. Almost.

"I never asked for your trust, child. Only your obedience."

Then the Helvault claimed her, and she vanished into a darkness vast and total.

Repose

Interlude

Through darkness, she fell.

She knew no other sensation—no sound, no light. Not even a breath of wind, for within this place there was nothing, not even air. Nothing but her, and the endless sensation of a descent forever unfinished. She couldn't see her hand in front of her face—was not entirely sure that she had a body at all, in this place.

She extended her senses outward, pushed and pulled with her powers of lithomancy, trying to get some kind of grip on the silver exterior of the Helvault. But what was around her was not silver. It was nothing. She tried to planeswalk, but even the Blind Eternities, the chaotic no-place between planes, was beyond her reach.

It was not like her cocoon of stone back on Zendikar, the slab of rock where she had slumbered for five fitful millennia. In her cocoon, dreamlike, she could sense all of Zendikar, reach out to any part of it, appear wherever she wished.

This was much, much worse—only darkness, and falling, and the unmistakable scent of Sorin Markov.

Sorin would pay for his treachery. She would escape from this prison, and she would make him pay. She'd thought they were allies. Friends! Now she saw him for what he truly was: a monster, plain and simple.

A monster. But not a fool. He knew what was at stake, back on Zendikar. He could not be so confident in his defenses, in his Helvault and his enslaved angel, that he would simply allow the Eldrazi to escape. He would free her, when he'd recovered his strength and prepared to face her. Would ambush her and defeat her, and allow her to go home. He couldn't just leave her here. It was unthinkable.

But she had a lot of time to think.

At length, she came to a decision.

"That's enough," she said quietly.

There was no reply, no sound at all. Her words didn't echo, but faded away into the infinite blackness.

"That's enough!" she said, more loudly. "Whatever lesson you're trying to impart, I've learned it. End this, and I'll depart Innistrad and never return. Clearly there's nothing left for us to say to one another."

There was no answer. And she wasn't about to apologize, and she certainly wasn't going to beg. She wouldn't give him the satisfaction.

She thought of Zendikar often, of its jagged peaks and yawning skies. Of the cancer that ate at its heart, of vampires swarming its surface, building statues of gods more monstrous than they knew. She should never have left.

The isolation began to gnaw at the edges of her sanity. Even a Planeswalker, even one who had spent millennia in stone, was not meant for this kind of solitude. Even a Planeswalker could lose her mind—and for a Planeswalker, who was a mind, the consequences would be horrific. She had met a mad Planeswalker, once. Once was more than enough. She would not go mad.

At first it was the thought of vengeance that she held on to, of crushing Sorin for what he had done to her, for what might be happening on Zendikar even now. But there were only so many ways to imagine killing him, and even now the thought brought sorrow and weariness more than the cold satisfaction of revenge. Her hatred never wavered, but it crystallized and grew still.

Her memories of Zendikar became her lantern in the dark.

She knew her world down to its bones, and her memory of it was perfect. She thought of a place—of the trenches in Akoum that her tribe had wandered, before she had abandoned mortal life and sunk into the stone. In her mind, she built a model of those trenches, tracing out each layer of basalt, each shard of red volcanic glass that made up the regolith, every grain and fault within the bedrock.

It was not Zendikar. It was Zendikar as she remembered it—after the Eldrazi, but before her slumber had allowed the world to drift out of control.

She worked her way outward through Akoum as time passed uncounted, remembering the grain of every sedimentary deposit, the temperature and viscosity of the magma that pulsed beneath the surface. She built downward, miles down, as deep as she'd ever dared go, until she had traced the edges of the tectonic plate that carried all of Akoum on its shoulders.

She held all of it in her mind, leaving parts of it unchanged for what seemed like years at a time, finding them again exactly as she had left them. Her mind was hers, and Zendikar was hers, and she would not let go of either of them.

It was impossible to say how long she'd been falling when her reverie was interrupted. She was no longer alone in the darkness. They were distant, at first—just a far-off keening, or the rustle of leathery wings. The soundlessness of her captivity had not been immutable, only the result of its emptiness.

Slowly, over countless years, the Helvault was populated. She understood, now, its purpose. Sorin would not tolerate threats to his precious Innistrad, and he had made this thing—this pit, this nowhere—to house them.

Threats, like demons, and horrors. And her. She spent a year or ten fuming, after that realization.

The other half, he had said. She very much doubted that he was personally imprisoning all these demons. She came to understand the angel's purpose in all this—however Sorin had duped or suborned her.

Eventually she had recreated all of Akoum in her mental geography of Zendikar, from the massive peaks of the Teeth of Akoum to the still waters of Glasspool. The water that surrounded her remembered continent was a sketch, a hasty scribble, by comparison—she didn't truly understand how water moved, and so the waves that lapped at the red cliffs of Akoum only sloshed back and forth. She didn't focus on them, lest she break the illusion.

She only had to make a little seafloor before she could start on Ondu. She was especially looking forward to the islands of the Crown, with Valakut its blazing jewel. But she refused to do things out of order. She had all the time in the world.

The others began to impact Nahiri, to glance off her in the endless darkness. She never saw them—that had not changed—but she heard them, shrieking, in the last instant before they struck. A talon here, a wing there, a momentary contact with a patch of nameless, inhuman flesh. And then gone, back into the darkness.

She marked time by those distractions, by those brief and senseless run-ins with the things that inhabited the dark. She did not hate them, even when their numbers swelled and their impacts against her not-quite-body grew more frequent, and more painful. She had no love for demons—had put down more than one to keep them from plaguing her world—but she did not hate them. Not here.

She pitied them. They were prisoners, like her, of Sorin Markov and his angelic enforcer. And unlike Nahiri, they would never have a chance for revenge. They were pathetic creatures, wailing and gibbering, mad or terrified or both—lesser minds, cracking under the strain of an eternity in the dark.

Nahiri was accustomed to isolation, and her mind was her own. In this blackness, it was all she had: her sanity, her anger, her memories of Zendikar...and a great deal of time.

She finished with Ondu, taking extra time on the sacred peak of Valakut. She'd spent years meditating in the volcano's caldera. Her Zendikar was her anchor, the thing that reminded her who she was and where she came from. She needed to get it right.

Sometimes she went back to that caldera, in her mind. But she couldn't content herself with just dwelling in her Zendikar. Not until it was finished.

Murasa was quick work, a great slab of stone rising out of the sea. The continent's forests were remarkable, but they did not interest her, and she made no attempt to recreate them. Bala Ged held her attention for a very long time, tracing the shifting contours of Bojuka Bay and the twisting network of caverns beneath the Guum Wilds.

After that it was on to Guul Draz—dull, for the top layer, but just as fascinating as Bala Ged below the surface. She was halfway through crafting the subterranean lava tubes that drove the continent's churning geothermal marshes when—at last, after untold years—something changed.

Light—a brief flash, blinding in the darkness, scattering her focus and, for a panicked moment, obscuring her Zendikar entirely. And then there was something with her, a presence more substantial than these wispy, wailing demons. Sorin? she thought, for an instant—but no. Not him. Not...quite. Far below Nahiri, twin suns ignited, illuminating nothing, and she heard the faint rustle of feathers.

The angel—here? In her own prison? That was interesting.

The lights drew closer, and now Nahiri could see—see, for the first time in centuries. The angel's spear flashed, and she grunted with exertion as she swung it in wide arcs around her. Her wings were spread, uselessly, trying to push against nothing at all.

The demons swarmed the angel, shrieking and flapping. They'd left Nahiri alone all these years, glanced off her only incidentally. But they knew their jailer. They knew their only chance for vengeance.

The angel rose toward Nahiri—slowly, slowly, in this timeless void—until they were side by side. The cloud of demons had dissipated as Sorin's protector gained the upper hand. The angel looked over at Nahiri, and for a moment their eyes locked—and finally Nahiri understood. Sorin hadn't enslaved an angel. He hadn't tricked her or coerced her. This angel stank of Sorin, just like the Helvault.

He had made her. Just like the Helvault.

The angel recognized her, from their long-ago fight. Dark eyes flashed with fury—fury Sorin had instilled. He had created her in his own image, twisted her from the beginning. Made her hateful. Made her his. Nahiri shuddered.

Another being grievously wronged by Sorin Markov, one with no chance of vengeance or redress. No chance of freedom. A porcelain doll, to replace the student he had lost.

Nahiri couldn't say how long they fell like that, together, looking into one another's eyes. Speech seemed impossible, after all this time.

And then there was light, real light, as the void around them cracked and shredded and finally...

she was...

out...

Ruin

One year ago

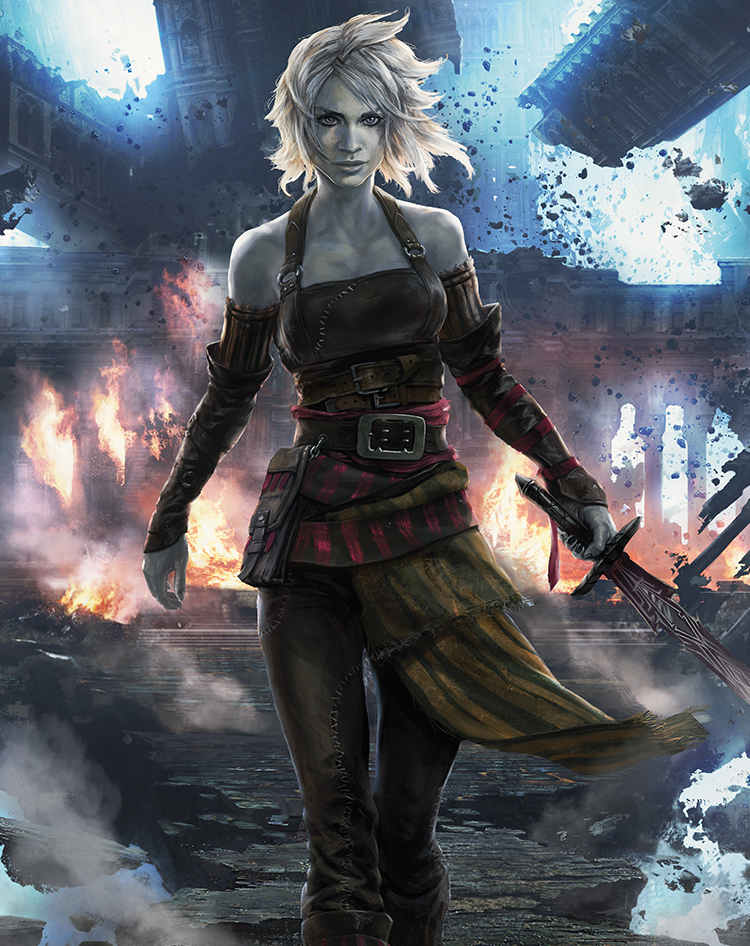

Nahiri slammed into a surface on her hands and knees, her endless fall over at last. Her eyes rejected the notion of light, her ears assaulted by a blast of cacophonous noise. She focused her vision, and the blinding light resolved itself into shapes, the racket into voices, the rough surface beneath her into a tidy little cobblestone street. She raised her head. People were shouting and running everywhere, fires blazing, corpses—corpses?—shambling, and above it all was Sorin's damned angel rising into the air in a beam of white light.

And all around her fell shards of silver.

Her hands felt strange. Feeling...felt strange. She looked at her palms. They were bloody. Bloody. She willed the wounds closed, but nothing happened. Her body was no longer an extension of her sense of self. Once again, as it had been long ago, it was just...a body. Flesh and bone. She could feel the blood pumping through her veins, the heaving gasps forcing air into lungs that had needed none for millennia. The world spun around her.

She had to leave. Before he found her. If she could leave, if she was even still a Planeswalker.

She pushed against the walls of the world, experimentally, and tried to move in that unreal direction only Planeswalkers could sense. She felt the walls of the world around her—she was still a Planeswalker, whatever had happened to her body—but as she probed them, those walls proved far firmer than she remembered. They had been a soap bubble; now they were a barrier that would take will and time to overcome. Was she so diminished?

But no. No. She pushed, the way she always had. The problem wasn't strength. The walls really were higher, thicker. The Blind Eternities were less connected to this place than they had been when she arrived. The shape of the universe had changed, while she fell. She could feel it.

She was still a Planeswalker. Whatever that meant.

With effort, she cast herself into the Blind Eternities. They tore at her, assailed her, just as they always had. Disoriented as she was, there was only one plane she could possibly have reached—the one he would expect her to run to, if he were looking. But there was no helping that.

Her feet found the rocky earth of Zendikar, and for the first time since her imprisonment began, she stood on solid ground. Zendikar, the real Zendikar. Home. She stood not far from where she had left, so long ago. In Akoum's jagged heart, near what should have been the Eye of Ugin.

But the Eye was a ruin, collapsed in on itself. Fields of rubble spread out beneath her and around her, hedrons and shards of red volcanic rock spinning lazily through the air. Its careful geometries, the meticulously placed hedron array that had surrounded it, and the chamber itself were simply...gone.

No. No.

The three Eldrazi titans had escaped, while Zendikar's protector languished in Sorin Markov's pit. Everything she'd built here, everything she'd worked for, had come to ruin during her long imprisonment.

Nahiri clenched her bloodied fists. Where? Where were they? Maybe the Eldrazi had left Zendikar. Maybe her world was finally free of them.

She stretched out her senses through the stones around her until she felt a familiar tremor nearby, just the barest quivering—the light and agile footsteps of her fellow kor. She climbed a ridge to reach them, coaxing the stones to keep her upright so she could spare her bleeding hands. The wounds still would not close.

A cry went up from a sentry, and Nahiri yelled hoarsely, her own voice a stranger to her. It was an answer-cry, a wordless signal that meant simply, I am kor.

It was only a handful of breaths before a dozen weary-looking kor surrounded her.

"You're hurt," said one of them, a tall woman with a strange, puckered scar across her bare shoulder. The inflections were different, the rhythms strange, but they spoke the same language. The tall woman raised her hands, setting them aglow with healing magic. Nahiri nodded, and the other woman touched her palms, closing the angry scrapes opened on another world by cobblestones and moon-shards.

"I'm Tenri," said the woman, as Nahiri's wounds closed.

Nahiri did not respond, and tried to look absorbed in the healing process. She didn't know how much they remembered of her—or, more to the point, of the baleful Nahiri the Prophet, whose statue she had seen even before her time in the Helvault.

"You're alone," said the sentry, a man festooned with weapons and ropes. "With no gear."

"It's a long story," said Nahiri. "I'm...a hermit, I suppose. I've been shut away for a long time, and things have changed. What has happened to the world?"

They gaped at her.

"The Eldrazi and their works are everywhere," said the sentry. "Where have you been, that you do not know them?"

"Hush, Erem," said the tall woman. Tenri. "She has no gear because she's a stoneforger, and she's probably been in solitude honing her craft."

"Something like that," said Nahiri. She straightened the red armband that marked her as a stoneforge master, marveling that her people's traditions had survived so much upheaval and so long without guidance.

"Last year," said Tenri, "three enormous monstrosities rose out of the Teeth of Akoum. Apparently they've been slumbering below the surface for a very long time. Their spawn spread everywhere, but the three, the titans, were worse. Where they go...nothing remains."

"There are some," said Erem, "who believe that they are Kamsa, Talib, and Mangeni in the flesh."

Several of the kor spat. Nahiri knew only one of the names, Talib. She'd seen it carved beneath a statue of herself, calling her its prophet. During her long absence, and her longer reverie before it, half-remembered stories of the Eldrazi—stories that she, in many cases, had first told—had passed into legend. The monsters that lurked within Zendikar had become its gods.

Nahiri spat too.

"Nothing remains..." she echoed. "Where? Where have they been? What have we lost?"

"Bala Ged," said Erem.

Nahiri waited for him to say more, to say which parts of Bala Ged were gone. He said nothing.

Bala Ged. An entire continent...

"I need to see it for myself," said Nahiri.

Erem snorted. Bala Ged was a very long way from here. Tenri nodded.

"I can outfit you, before I go," said Nahiri. "It's the least I can do."

Erem shook his head.

"We've no shortage of gear," he said. "Not when we've lost so many."

"Gods go with you," said Tenri. "Whatever gods you can muster, these days."

Nahiri clasped the taller woman's shoulder.

"Thank you for your help," said Nahiri. "And I'm sorry I couldn't do more."

She sank into the stones beneath their feet, leaving behind her fellow kor—strangers to her, as like to her as she was to Sorin.

She felt the extent of the damage. The deep places of the world were riddled with new tunnels, crusted with some strange substance that confounded her senses. Everywhere she looked, there was devastation. Everywhere were signs of the Eldrazi, landscapes eroded in ways she couldn't even understand. And far away, across the world, in Bala Ged—

She concentrated—it took concentration, now—and shifted herself across her world, looking for the source of the wrongness. She felt woozy, sick. She should wait, and rest, and recover her strength.

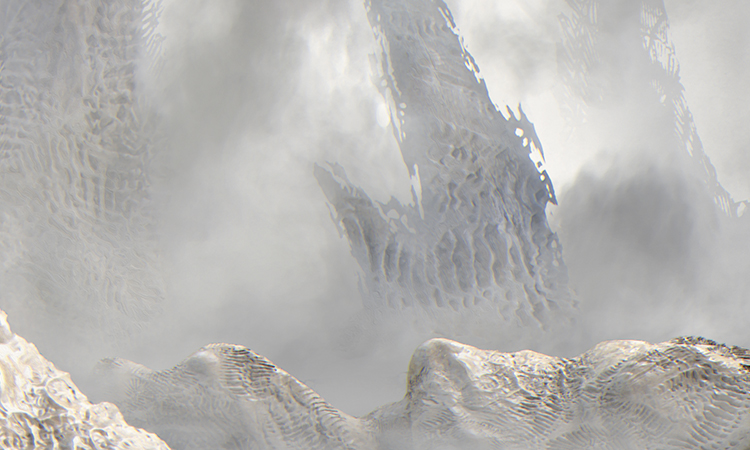

She had had enough of waiting. She had to see what was happening. She appeared in Bala Ged, in what should have been lush jungle. What stretched before her was a seemingly endless expanse of chalky gray dust—more lifeless than any desert, like the surface of a moon.

There was nothing like this on the Zendikar she still held in her head, the mental model she had painstakingly built over the years of her imprisonment. On her Zendikar, Bala Ged was living and wild. On this Zendikar, it was dead. Nothing lived here. Even the rocks were silent.

The ground trembled beneath her feet, and she could not feel the source of the tremors. The dust shivered.

She turned. There, on the horizon, vast and horrible, was a being she had seen twice before—once on a world lost to the Eldrazi, and once when she imprisoned it and its brethren on Zendikar. The Devourer. The one Ugin called Ulamog.

Nahiri fell to her knees, pressing her hands into that lifeless dust.

If this was loose on her world—

If what happened here could happen everywhere—

If she had no preparations, a thin shard of her old power, and a hedron network centuries out of true—

Then the Zendikar she knew was dead. There was no saving it. One might as well try to stop the sun in the sky. She closed her eyes and saw her Zendikar, Zendikar as it had been. The world she had let Sorin Markov destroy. Hot tears of rage ran down her face and landed in that awful dust with a hiss.

"As Zendikar has bled, so will Innistrad."

She opened her eyes and looked down at her hands, at hands that had shaped stone and trapped titans. They were covered in gray dust.

"As I have wept, so will Sorin."

She looked up at the thing on the horizon, watching it move across the landscape like a natural disaster.

"This I swear, on the ashes of my world."

Nahiri stood.

She had a great deal of work to do.

Shadows over Innistrad Story Archive

Planeswalker Profile: Sorin Markov