Revelation at the Eye

Previously in the Battles at the Brink arc: "Nissa's Resolve"

Next in the Battles at the Brink arc: "Shaping an Army"

Editor's Note: This story was originally published on October 14, 2015.

Jace Beleren is not a fighter. His immediate goal in coming to Zendikar was to solve a puzzle: the question of how the plane's floating stone hedrons had contained the Eldrazi, and how they might be used to capture—or kill—the titan Ulamog, who remains on Zendikar.

With all the scholarship on the subject destroyed in the fall of Sea Gate, Jace was forced to undertake a dangerous journey to the Eye of Ugin, the center of the hedron network. Jace had been there once before, when he inadvertently helped release the Eldrazi. Now, he must return to the Eye and unravel the puzzle of Zendikar's hedrons.

If he can live that long.

Jace Beleren wedged his boot against a jagged rock, pushed, and stretched, barely wrapping his aching fingers around the next handhold.

He was not exactly in his element. The wind whipped his cloak around him. He didn't look down.

He wasn't afraid of heights, not more than the average person. But he knew how high up the cliff face he was, and looking added no useful information. And anyway, a certain amount of wariness seemed rational, given that a fall from this height would certainly kill him, splattering him against the . . .

He didn't look down.

Looming Spires | Art by Florian de Gesincourt

At the top of this cliff, if the mental map he'd pulled out of Jori En's mind was accurate, was what passed for even ground in Akoum, a vast expanse of jagged volcanic rocks and treacherous canyons. The Tuktuk tribe of goblins lived somewhere in this area, or had before the Eldrazi rose. The landscape had been rearranged when the three Eldrazi progenitors physically emerged from the mountain range known as the Teeth of Akoum, and neither Jace's prior experience nor Jori's knowledge could guide him. He needed help. He needed Tuktuk and his tribe.

Inch by inch, handhold by handhold, Jace pulled himself up the rock face. At last, hands aching, he hauled himself over the lip of the cliff—

—and straight into an Eldrazi.

It was small, as Eldrazi went—perhaps as big as he was—and its blank, bone-white face was just a few feet from his. He stumbled backwards but caught himself, one boot dangling out over the abyss. He rolled sideways and got to his hands and knees out of easy reach of the thing.

Salvage Drone | Art by Slawomir Maniak

The Eldrazi was looking at him, its eyeless face swiveling to follow his movement. It lunged.

Jace pushed himself to his feet, summoning an illusionary guardian. The Eldrazi's mind was as blank as its face, and none of his usual tricks seemed to work on them. Sleep magic did nothing against things that didn't sleep. Invisibility was useless against monsters without eyes. Even his illusions seemed to falter against these otherworldly adversaries.

The Eldrazi tore through his illusion like it was paper and kept coming.

With more time, Jace could have conjured up a more solid illusion. With more time, he might have been able to confuse the creature long enough to get away—to try out tactile or auditory illusions that might misdirect it. He was out of time, and exhausted from the climb, and all he could do was try to wedge himself between two of the sharp rocks and hope he could get a few good kicks in.

There was a thwack, and a flash of bright blue light. The Eldrazi reeled. Jace blinked. What . . . ?

"Down, foul thing!" came a voice from his left.

The Eldrazi swiveled its bony face to look—or the eyeless equivalent—just as a heavy club came down on its blank white head. There was a sound like shattering porcelain and a splatter of meaty goo, and the Eldrazi dropped.

Jace peeked around the rock next to him to see a squat goblin grinning from ear to ear. Like most of the goblins he'd seen since his return, she had a heavy metallic growth on the top of her skull. She had a heavy basket on her back and a stone club—no, not a club, he realized, and not a basket. A pestle and a mortar. The goblin stood only as tall as his waist, but she had to be monstrously strong to lug those around.

Zada, Hedron Grinder | Art by Chris Rallis

"Hello!" said the goblin with, it seemed to him, undue cheer. "Not safe, traveling alone."

She wiped her pestle on a rock, scraping off bits of bone and whatever passed for an Eldrazi's brain. Jace didn't want to go rooting around in her head just yet. That had a way of hindering potential good relations.

"Thanks for the save," he said. "How did you do that? To the Eldrazi?"

"Oh, their skulls bust just as easily as yours," said the goblin. She rapped the top of her head, which clanged. "Bit easier than mine."

"Before that," said Jace. "The spell, or whatever it was."

By way of response, she looked around as though she'd lost something, then shouted "Aha!" and scrambled to pick up what looked to Jace like a small rock. No—not a rock. A shard of one of Zendikar's magical stone hedrons.

"A hedron holds magic for a thousand years," she said. "Or less, if need be. This one's mostly spent, but I'll grind out what I can."

She cackled, tossed the hedron into her mortar, and started absentmindedly pounding away at it. There were sparks and pops.

"The size of 'em doesn't tell you much," said Zada. "Every hedron's like a deep, dark hole. Could be filled with good stuff. Could be empty. Only way to know for sure is to dive in."

"I see," he said. "Uh . . . I'm Jace, by the way."

"Zada of Slab Haven," said the goblin, as though that explained everything.

"I'm looking for Tuktuk," said Jace. "Do you know him?"

For some reason this made Zada roar with laughter.

"He's dead," she said. "Stone dead, you might say."

She started laughing again, but at Jace's blank expression, she managed to wheeze out, "He was made of rocks, you know."

"What happened?" asked Jace.

"I ate him," said Zada.

Jace spent a moment imagining horrific cannibal rites until he remembered what she'd just said about Tuktuk, which pushed her claim from horrifying to merely improbable.

"You what?"

Zada grinned again, showing off rows of enormous pitted teeth.

"I. Ate. Him."

"I thought you said he was made of rocks," said Jace.

"Yep," said Zada. "You don't know much about goblins, do you?"

"I really don't," said Jace. "Why did you . . . eat him?"

"When we find hedrons and other magic rocks, we grind 'em up and eat 'em," said Zada. "Makes us stronger. Tuktuk had us doing it. But then I figured, Tuktuk was the most magic rock of all . . ."

She shrugged and patted her belly.

"That . . . makes a weird kind of sense."

"Thank you!" said Zada.

"Uh . . . anyway," said Jace, "what I'm really looking for is the Eye of Ugin. I've been there before, but everything seems to have changed."

"Why?" said Zada.

"To stop the Eldrazi," said Jace. "I need to learn more about the hedron network, and the Eye of Ugin is its center."

"Was," said Zada. "A scrambled mess doesn't have a center."

She sighed.

"But I suppose I'll show you the way, if you think it's important," she said, gesturing for him to follow. "Not sure what all the fuss is about, though. We're getting along fine up here . . ."

It was a few hours' hard walking to the Eye, as Zada picked a winding path through the precarious spires of Akoum. Twice they had to double back to avoid Eldrazi, and even Zada seemed a bit lost in the tumultuous landscape. All the while she nattered on about the nature of hedrons. Jace hadn't realized they actually stored energy, or that their energy could still be directed against the Eldrazi, so at least he was learning.

Eventually Zada pointed him at a cave entrance and bade him farewell.

"You're not coming in?" said Jace.

"Nope," replied Zada. "Nobody goes in there. Bad magic. Certain death. Good luck!"

She bounded away over the rocks, and Jace turned to the ominous, angular mouth of a cave that certainly was not natural stone.

He descended carefully, picking his way among enormous fallen hedrons. The place was silent, lifeless, devoid of the thrumming power that had suffused it on his last visit. His illusionary light threw strange shadows through the vast and ruined space. If the Eye was dead, if whatever power had animated it was now gone, he might not learn anything after all.

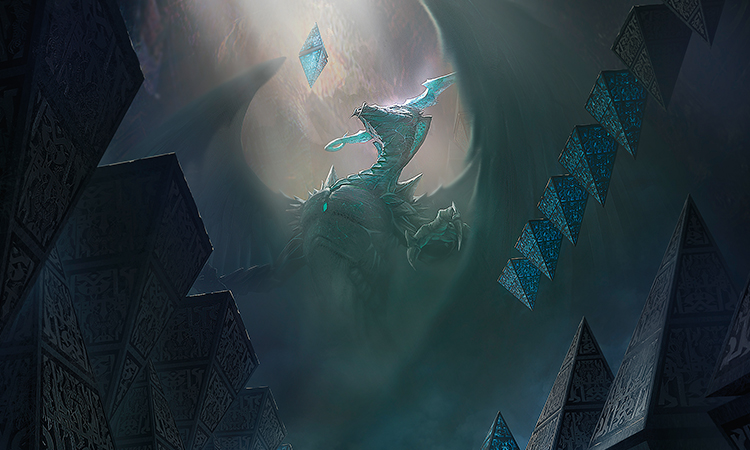

Sanctum of Ugin | Art by James Paick

A cold, blue-white glow shone up ahead—were his eyes playing tricks? He snuffed his light. Yes. A glow. That meant—what? Some life remained in the Eye after all? Or someone else was already here?

He stepped carefully now, with so little light, down the path of jagged hedron shards. As he walked, the stones around him became more orderly—their faces and runes repaired, their alignments corrected.

"Welcome back," said a voice. It was smooth and powerful, seeming to thunder from the stone around him. "I hope you didn't come alone. My preparations are nearly complete."

A shape unfolded itself from the shadows of the enormous cavern. Horns glinted and wings unfurled, and an enormous dragon made a short glide toward him. Jace took a step back, heart racing. Bolas?

No. Not Bolas. This dragon was glowing from within with the soft light Jace had seen earlier.

The enormous shape settled before him, wings outstretched.

"Hmm," said the dragon, frowning. "You're not who I was expecting."

"I could say the same," said Jace. "Who are you?"

The dragon regarded him.

"Do you know the name of this place?"

"I do," said Jace. "But I'm not going to let you claim to be what I'm expecting. What's your name?"

The dragon smiled, keeping his teeth hidden.

"Fair enough," said the dragon. "My name is Ugin. I helped build this place, long ago."

Jace had assumed Ugin was long dead, if indeed Ugin had ever been a person at all. Yet here he was, in the luminous flesh. Jace tried to read the great being's mind, to verify his story, but found it as smooth and dazzling as a wall of crystal.

Ugin, the Spirit Dragon | Art by Chris Rahn

"My name is Jace Beleren. I'm here to learn about the hedron network. I didn't imagine I'd find one of its builders."

"You've been here before," said Ugin. It was, unfortunately, not a question.

"Ah," said Jace. "Yes. Once. It . . . didn't go well."

"You released the Eldrazi," said Ugin.

"I—" said Jace. "Yes. There were three of us. We fought. The chamber—"

"I know," said Ugin. "You, a pyromancer, and a dragonspeaker. Planeswalkers all. You opened the Eye."

How did he know that?

"It wasn't our fault," said Jace. "We were—"

"Manipulated, yes," said Ugin. "By another dragon Planeswalker, a rival of mine—"

"Oh, no."

"—Nicol Bolas. You know him?"

"We're acquainted," said Jace. "This wouldn't be the first time he's manipulated me."

"It is his nature," said Ugin.

"Why?" said Jace. "Why would he want the Eldrazi released?"

"That," said Ugin, "is an excellent question, one I will devote considerable resources to answering. At the moment, however, we must do, in all likelihood, exactly what Bolas wants us to do, and that is focus on the Eldrazi."

"We'd better hurry," said Jace. "One of the Eldrazi titans is headed for Sea Gate right now."

"Sea Gate?" said Ugin.

Jace froze.

Mighty Ugin, creator of the Eye . . . didn't know Zendikar's greatest city?

"How long have you been away?" said Jace.

"Ages," said Ugin, with a tone that suggested the literal meaning of the word. "I was detained. Sea Gate?"

"A center of civilization and learning on the coast of Tazeem. They had scholarship on the hedrons, but it was lost to the Eldrazi. Now Ulamog is headed toward it to devour the survivors gathered there."

"Do not assume," said Ugin, "that you know anything of the minds of the Eldrazi. Ulamog goes where he does and does what he must."

"But they're drawn to concentrations of life, aren't they? There is a logic to their movements."

"They are and there is," said Ugin. "If survivors have congregated at this Sea Gate, then Ulamog could be seeking them out."

"We've got to stop him," said Jace. "Incapacitate him, kill him—whatever it takes."

"You cannot kill Ulamog," said Ugin.

"Stop him, then. Whatever we do, we need to do it now. People are dying. We have to do something, and thanks to your hedrons, we've got all the plane's leylines at our disposal. What do you suggest?"

Jace began to gather mana, a sensation like the rush of knowledge and a deep, cool current.

"I have allies, ancient and powerful ones," said Ugin. "The two who helped me imprison the Eldrazi on this world thousands of years ago . . . they can help. You've begun to understand the hedrons' true purpose. The Eldrazi can be imprisoned."

"And how did that work out last time?"

Hedron Archive | Art by Craig J Spearing

The dragon shifted. Rose. He felt it too, then, that nagging sensation that they might not be on the same side after all.

"Perfectly," said Ugin. "Until you and your cohorts let them out."

"You'll forgive me," said Jace, "if I take cold comfort in knowing that three people who knew next to nothing about any of this were able to overwhelm your security measures by accident."

"It was not an accident," said Ugin. "It was carefully orchestrated. Don't make the mistake of thinking your plans are the only ones that matter."

"Didn't you make the same mistake? You thought no one would want the Eldrazi released from their prison. But Bolas does. And if he wants them out, he can orchestrate them right back out again."

"You're still making assumptions," said Ugin. "Whatever Bolas wants, it's entirely possible he's already achieved it. And as you say, people are dying. We would be fools to pursue the impossible simply because you believe the achievable is flawed."

"Impossible is a hell of a word, coming from you," snapped Jace. "You know a lot more about the hedrons than I do, but all you can talk about is what we can't get done. You must have a better idea. Well? I'm listening!"

A rush of mana, a spell from the great dragon—but not an attack. An illusion. A network of scattered nodes and gently curving lines drawn in bright white light. Jace let it come.

"The hedron network," said Ugin, "as it was."

The dragon's voice was amplified, booming, echoing from within every one of the angular stones that made up the chamber's walls. The diagram grew larger and larger, a bright ring in the center looming balefully—the Eye of Ugin. Jace tried to take it in, but it was too much—too vast, too complicated, a knot he couldn't hope to untangle in a hundred lifetimes. A knot that Ugin had made.

Then it changed. Nodes drifted; some vanished. The curves of the leylines—certainly, they were leylines—began to change. Within a few seconds, the network was disordered, chaotic.

"The Lithomancer who made these hedrons has been gone a long time," said Ugin. More illusions flared around the dragon, multiplied images of a kor woman with a broad smile and fierce eyes. Then she vanished. "Gone, or careless. Without her, the hedrons drifted. Then . . . you arrived. The Eldrazi were awakened, their brood lineages unleashed upon Zendikar. But my fail-safes remained in place. The Eldrazi were not yet free."

More change. Order. The network reasserted itself. Nodes arranged themselves back into curves, then into lines. What had been gentle, looping, a sort of cosmic finger-trap, became rigid, binding, strong. Jace stood rooted in one spot, unable to turn away from the abstract vision of a nightmare.

Island | Art by Vincent Proce

"The network tried to contain the Eldrazi, just as it was designed to," said Ugin. "Without further interference, it might have succeeded. Then someone—or was that you too?—opened the last lock, dismantled the final fail-safe."

The diagram fractured. The nodes scattered. The lines went haywire. The Eye at the center went dark, so that Jace could see Ugin himself through it.

"The hedron network as it stands," said Ugin. "This is what we have to work with, Beleren. If three Planeswalkers at the height of our power could not kill the Eldrazi titans with the hedrons in full working order, what makes you think you and I can do it with this sad remnant?"

Jace gritted his teeth. Enough of this. Enough.

"You're speaking in abstractions," he said.

He fired off a counterspell to tear through Ugin's illusion, and sent up a few of his own. Sea Gate at its height, when Jace had visited it shortly after the Eldrazi rose. The survivors' camp when he'd been there weeks ago, where the same scholars, now diminished in number and in hope, huddled around campfires. Gideon, standing tall, inspiring people. Nissa communing with the land.

Dispel | Art by Chase Stone

"Zendikar isn't a puzzle to be solved," said Jace. "It's a place. It's somebody's home. And those people are out there, right now, fighting for their world and wondering if anybody's going to help them kill what's killing them."

He showed scenes of suffering, then—of families mourning the lost, of landscapes ravaged by Ulamog, of even the skies and seas teeming with the Eldrazi menace.

Ugin cocked his head. The hedron architecture of the chamber seemed to melt and flow, became a pattern of tessellating dragons mocking him from the walls.

"So certain," said Ugin, "and so young."

The diagram sprang back, crowding out Jace's images. Then it changed again—restored, as much as its current state allowed. It had fewer nodes, more sharply curving lines. A pattern. A glyph—circular, with three points at equal intervals around the circumference. He'd never seen the glyph before, but immediately he understood it. Leylines. If the leylines of Zendikar could be coaxed into this shape . . .

"The Eldrazi can be imprisoned," Ugin said again. "You speak of killing them as though they were houseflies. You shouldn't—and you can't."

"Don't tell me about can't," said Jace. "Tell me about will or won't. Kill them, trap them . . . it's irrelevant. All of it. I came here to stop them. So did you. Right?"

Jace's illusions flowed and changed without his willing it, became enveloped by the vast abstraction of the hedron network.

"Your knowledge of the hedrons," said Jace. "My knowledge of Zendikar on the ground. Of a place called Sea Gate. Of the people here and why they're worth saving."

"Do not lecture me about what is worth saving," said Ugin, his voice booming. "There is more than this world at stake—certainly more than the people who happen to be alive here at the moment. You come to me speaking of the threat of Ulamog. But do not forget: They came as three. With the Eldrazi at large, the entire Multiverse is at risk. That is what I am here to save, Beleren. The Multiverse, in all its vastness of time and space. Not the people you shared a cookfire with."

Dragon and diagram became one, luminous and looming. Lines and nodes, wings and horns, the shapes of hedrons, and at the center one glowing, glowering Eye. Jace faltered under its gaze.

"Tell me what to do, Ugin. Tell me how to help."

The Eye pulsed. Jace's consciousness began to fade.

Then it was gone. Ugin's illusions, Jace's, all of it. Only the chamber and the dragon remained.

"You truly want to help?"

"That's why I came here," said Jace. "I did have a hand in releasing the Eldrazi. If I can take part in stopping them, I will."

"I said earlier that you weren't who I was expecting," said Ugin. "My allies, the two who helped me imprison the Eldrazi thousands of years ago . . . are not here. One is missing. I sent the other after her. I've heard from neither since. They are needed here, urgently. Have you heard of a Planeswalker named Sorin Markov?"

Art by Igor Kieryluk

"No," said Jace. "Should I have?"

"Only because of his connection to this place," said Ugin. "He is my erstwhile ally, self-proclaimed lord of his home plane of Innistrad."

One of Liliana's favorite haunts, though Jace had never been there.

"That I've heard of," said Jace. "You could say I have an ally there myself."

You'd be kidding yourself, he thought, but you could say that.

"Good," said Ugin. "Sorin is crucial to our efforts. If you want to help, then seek him out, bring him here, but . . . do not trust him."

"What does that mean?"

"It means," said Ugin, "that although he speaks of the greater good, he is a selfish creature. He fought the Eldrazi not out of compassion for Zendikar, but out of a very long-minded sense of self-preservation. If more urgent matters have consumed his attention, his priorities may not align with our own."

Jace wasn't sure if it was the longevity or the power, but he'd noticed that ancient Planeswalkers had something in common: They were all completely insane.

"What about your other ally?" said Jace.

"Nahiri, called the Lithomancer," said Ugin. "A kor of Zendikar, and its guardian. I do not know why she would leave this world, and I cannot imagine that she would stay away if she could possibly return. Something has happened to her. If you cannot find Sorin, find her."

"I'm not abandoning Zendikar," said Jace. "I've got friends here." Friends. Yes. Close enough, at any rate. "They're relying on me to return with information about the hedron network. Unless you want to go to Sea Gate and tell them yourself?"

"No," said Ugin. "I am needed here, at the Eye. I must rebuild the central chamber so that my associates can restore the network to its full function and trap the Eldrazi once more."

"Then I'm afraid your allies will have to sort themselves out," said Jace. "What can I do here?"

"The hedron network is damaged," said Ugin. "I will need Ulamog corralled. Contained, within a circle of hedrons. Will these friends of yours help imprison an Eldrazi titan, rather than try to kill it?"

"I think so," said Jace, though in fact he was far from certain. "But only if I can convince them it's the only option. They've seen plenty of Eldrazi die. And you still haven't told me why we can't kill Ulamog."

"The Eldrazi titans do not dwell in physical space," said Ugin. "They are creatures of the Blind Eternities, and it is in the Eternities that they remain."

"Until they manifest physically, you mean?"

"No," said Ugin. "I meant what I said. Ulamog remains in the Eternities."

"Then what did I see heading toward Sea Gate?"

"You saw a portion of him," said Ugin. "A projection. Imagine that you reach your hand into a pond. The fish below the surface sees a five-headed monster, and cannot perceive the man attached to it. It mistakes a hangnail for an eye because the truth is beyond its imagining. You see?"

"And when you trapped them . . ."

"Like driving a spike through the hand," said Ugin. "The man will not die, but neither will he trouble other ponds. 'Killing' Ulamog's physical form would be like cutting off the hand. The man might be diminished, but he would survive—and he would be freed."

"But the hedrons don't just direct leylines," said Jace, thinking fast. "They store energy. Vast amounts of it. That's how they pulled the Eldrazi in to begin with, isn't it?"

It was a guess, but it seemed a reasonable one.

"Correct," said Ugin. "Your point?"

Jace's mind raced.

If the hedrons could pull, then couldn't they pull harder? With enough power, couldn't they be used to draw the Eldrazi fully into the physical realm? If you had a spike through a man's hand, you could do a lot more than hold him there. You could pull him into the pond. And then . . .

"I . . . no, never mind," said Jace. "Sorry. Still wrapping my head around all this."

The dragon had made his position on killing Ulamog quite clear, and Jace himself wasn't at all sure it was a good idea. He understood the hedrons now. He'd seen the glyph. If Ugin would help them imprison the Eldrazi, then that was, at the very least, a good first step. And if the opportunity arose to do more . . . he'd be ready. And Ugin might not be.

"Of course," said Ugin. "Considering your inexperience, you're keeping up better than I'd expect."

It was intended as a compliment. Jace decided to take it as such.

"This . . . hand metaphor," said Jace. "It's describing the three titans. What about all the others? Does killing them free them too? Are there thousands of Eldrazi loose in the Eternities now?"

"Suppose the man reaches his other hand into the pond," said Ugin. "Does the fish face one monster, or two?"

Jace's patience for this method of imparting information was minimal, but he tried to give the dragon's question-answers due consideration.

"The fish sees two beings," he said, after a moment. "But they're part of one whole."

"Suppose the man has a hundred hands," said Ugin. "Or a million."

Understanding dawned. A wave of nausea overtook him.

"You're saying they're connected. Ulamog's brood aren't really spawn. They're . . . appendages."

"More like cells," said Ugin. "Organs, in the case of some of the larger ones. But all of them are replaceable—sub-lives that come into being, fulfill their function, and die or a reabsorbed, without diminishing the whole."

"So killing them does nothing, other than keeping them from killing you."

"Ultimately, no," said Ugin.

Jace ran a hand through his hair.

"All right," he said. "That's enough information. I'll present your plan to my friends at Sea Gate. I'll try to convince them that imprisoning Ulamog is the right course of action."

Ulamog, the Ceaseless Hunger | Art by Michael Komarck

"You must do more than try," said Ugin. "With the hedron network damaged and the fail-safe removed, the titans are free to leave the plane. If Ulamog is wounded, you could drive him away from Zendikar entirely. Away from the hedron network, and our best chance of stopping him. You understand why that would be a disaster. But it may not seem that way to the people of Zendikar. You must dissuade your friends from attacking Ulamog directly—and, if necessary, you must stop them."

"Understood," said Jace. "I'll tell them."

"Do not let them drive Ulamog away from Zendikar," said Ugin. "The consequences would be grave, and that justifies whatever means are necessary to stop it."

"You've made yourself clear," said Jace. "I won't let Ulamog escape."

One way or another, he thought.

"Good fortune, Jace Beleren. I will make sure my preparations are complete."

"I'll be ready," said Jace.

Jace turned, walked out of the Eye of Ugin, and stepped into the sunlight. He had a plan. He had a destination. He was ready.

One way or another.

Planeswalker Profile: Jace Beleren

Follow the Eldrazi story arcs May 13–17 on DailyMTG.com for more Modern Horizons 3 card previews and narrative background. You can also preorder Modern Horizons 3 products now from your local game store, online retailers like Amazon, and elsewhere Magic is sold.